More than simply buildings with exhibitions, museums seem to have a specific cultural identity about them: marble columns, grand atriums, security guards in every other room. But this idea may not be entirely accurate anymore. As with nearly everything in Western society, the internet has brought great changes to the world of museums. Many major institutions have at least partially digitized, publicly available collections; museums have also adapted to innovations like social media to further attendance. Alongside museums’ development in the twenty-first century, video games have arisen as one of the most popular art forms. Today, it seems impossible to walk into a room of twelve-year-olds and not hear a mention of Fortnite. Three games in particular– LSD: Dream Emulator, Kid A Mnesia Exhibition, and Dark Souls III– each show a potential example of video-game-as-museum. Through video games, museums may well be able to find a path forward in a rapidly changing, digitally-focused world.

First, however, it is important to define what a museum actually is. This may seem simple at first, but it is a deceptively difficult question. After all, what is it that links a grand, national museum like the Smithsonians and a tiny, one-room, community focused space like New York City’s Museum of Reclaimed Urban Space? (‘Museum of Reclaimed Urban Space.’ MORUS. Accessed November 23rd, 2023. http://www.morusnyc.org) Historians Carol Duncan and Alan Wallach propose that museums, at their core, serve as ritually and ceremonially important spaces, residing in the same social space as “churches, shrines, and… palaces.” (Duncan, Carol, and Alan Wallach. 1980. “The Universal Survey Museum.” Art History 3 (4): 448-69.) Today’s large, less independent museums (or at least the museums when Duncan and Wallach were writing) serve to educate the public, yes, but they also serve as concrete examples of the state’s power.

ICOM (the International Council of Museums) gives a more concrete (although very recently updated) definition:

A museum is a not-for-profit, permanent institution in the service of society that researches, collects, conserves, interprets and exhibits tangible and intangible heritage. Open to the public, accessible and inclusive, museums foster diversity and sustainability. They operate and communicate ethically, professionally and with the participation of communities, offering varied experiences for education, enjoyment, reflection and knowledge sharing. (“Museum Definition.” n.d. International Council of Museums. Accessed November 9, 2023. https://icom.museum/en/resources/standards-guidelines/museum-definition/.)

Both of these definitions have problems, however. It is hard to imagine a museum as innocuous as San Francisco’s Exploratorium as an extension of state power; at the same time the Exporatorium lacks traditional collections.‘Exploratorium.’ Exploratorium. Accessed November 23rd, 2023. https://www.exploratorium.edu/ Despite this, it seems fairly obvious that the Exploratorium is, indeed, still a museum.

Janet Marstine posits a more nuanced approach to the question, although perhaps not a satisfying one. To Marstine, there are four grand metaphors that can apply to some museums: “shrine, market-driven industry, colonizing space, and post-museum.” (Marstine, Janet. 2008. New Museum Theory and Practice: An Introduction. Newark: John Wiley & Sons, Incorporated.) Shrine museums, similar to Duncan and Wallach’s definition, serve as a shrine, or a space to worship something; an example could be the National Museum of American History. While NMAH does not give an uncritical view of this country’s past, it still does serve to celebrate American history. Market-driven museums, despite the somewhat condescending name, are museums that seek to “‘give in’” to market demands, choosing to cater to visitors instead of some lofty ideal of what a museum should be. (Marstine, Janet. 2008. New Museum Theory and Practice: An Introduction. Newark: John Wiley & Sons, Incorporated.) Colonizing spaces, as the name suggests, are museums whose collections are formed from the spoils of imperialism, using the “‘other’ to construct and justify the ‘self.’” (Marstine, Janet. 2008. New Museum Theory and Practice: An Introduction. Newark: John Wiley & Sons, Incorporated.) The post museum is the least helpful metaphor for defining museums, as it deals with the theoretical; it is a museum that has transcended museums, serving less a repository for knowledge and more as a way to better its community.

So, what is a museum? Well, it’s a space that, through one or more of Marstine’s four metaphors, focuses on educating the public about a specific topic, while often functioning as a societal and social ritual. Some, like the British Museum, use the excuse of public education to flaunt colonial plunder; others, like the Exploratorium generally just want to teach the public cool things about science. It is impossible to come to a full definition, however. No matter how broad or specific a definition is, there will always be spaces that fall outside of it: are zoos and aquariums museums? Are libraries? There is not, and will never be, a fully satisfactory definition.

Defining video games is quite a bit easier: a game where players use various methods of input to control and manipulate moving images created by a computer program. This definition is an intentionally open one: not all video games involve killing enemies or chasing a high score. Some feel more like pieces of art, or even entire galleries thereof. Take Asmik Ace Entertainment’s LSD: Dream Emulator, for example. Directly inspired by one of the developer’s decades-spanning dream journals, the game has players travel through and explore incoherent, dream-like spaces.[8] After each level (if they even be called that), the player is placed on a quadrant chart with “downer” and “upper” as the x-axes and “static” and “dynamic” as the y-axes. (Sato, Osamu, dir. 1998. LSD: Dream Emulator. Asmik Ace Entertainment.)

LSD is a video game, yes, but it doesn’t really behave like a game. The player is never scored; there are no other characters you can interact with; there isn’t even much gameplay besides walking around and observing the art. Much like, say, an art gallery. Ignoring the fact that it exists not as a physical structure, can LSD: Dream Emulator be considered a museum? The player isn’t really taught anything, but the same could be said about art museums whose labels include little more than the artist, the medium, and the year painted. The deciding factor, then, should be intent: are these video games or other digital media projects intended to be treated like a museum? For LSD, the answer seems to be no. It functions as more an individual art piece, something to be displayed in and of itself.

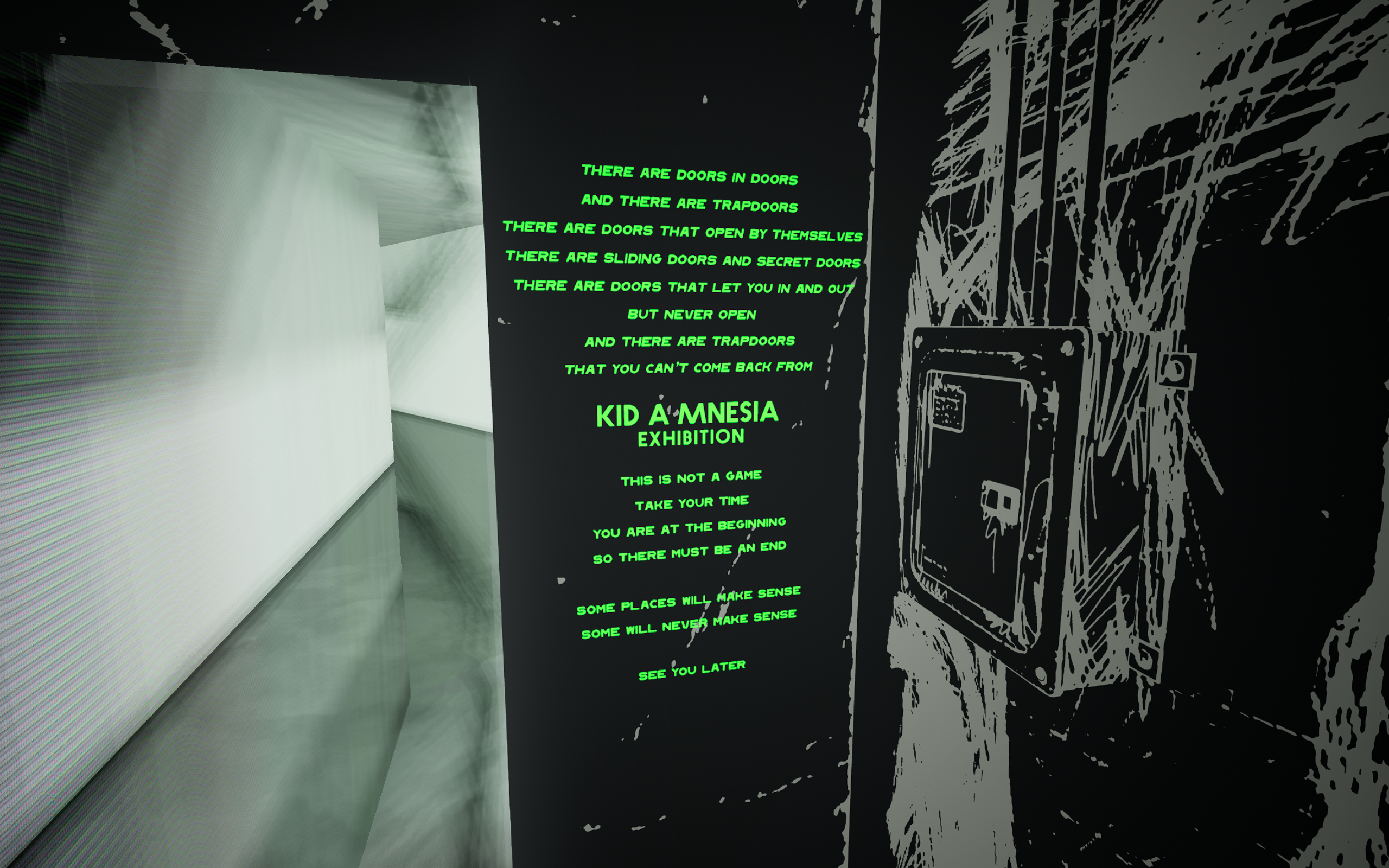

LSD Dream Emulator is by far not the only not-game video game to take on the language of art and museums. In November of 2021, British art-rock band Radiohead released Kid A Mnesia Exhibition. The game is best described as a visual arts museum dedicated to albums Kid A and Amnesiac; each song given a room with surreal, occasionally unsettling accompanying visuals. It may not exist in the real world, but the intention for this to be an actual, physical museum space was there from the start.

Thom Yorke, Radiohead’s frontman, and Stanley Donwood, Radiohead’s main artist, both initially wanted Kid A Mnesia to be an exhibit at the U.K.’s Victoria and Albert Museum. Intending to create the space by welding together shipping containers, the pair wanted it to look out of place in Victoria and Albert’s classical architecture, forcing it into London like an “ice pick into Trotsky.” (Yorke, Thom. 2021. Radiohead explain the story behind the creation of its Kid A Mnesia Exhibition, out today on PS5. Interview by Stanley Donwood. https://blog.playstation.com/2021/11/18/radiohead-explain-the-story-behind-the-creation-of-its-kid-a-mnesia-exhibition-out-today-on-ps5/.) But real life got in the way. The exhibit couldn’t exist at the V&A without serious structural damages; the Westminster council denied a change of location to the Royal Albert Hall; finally, COVID-19 hit and fully denied any plans of a physical exhibition space.

In many ways, Kid A Mnesia is more video game than museum. It has a pause menu and lets you “run” with the shift key; the exhibit even saves your progress if you close it and then reopen at a later time. But the game has a deeply vested interest in recreating the visual language of museums. Its rooms contain visible fire extinguishers, camera, and digital stick-figure maintenance staff; the walls guide players along much like at a “real” museum. It even recreates a near-universal museum experience: walking into a part of an exhibit with a short film and needing to wait an awkward amount of time for it to restart. Except, in this case, the short film is distorted footage of Thom Yorke creating a song with various synthesizers and the other museum patron in the room is a white, paper-mache imp staring directly at you.

If the Kid A Mnesia Exhibition is a museum, then it should be able to be described by one of Marstine’s four metaphors. It certainly isn’t a colonizing space, nor is it a market-driven industry; the game, after all, is free. It does match the criteria to be a shrine, however— a shrine, more specifically, to the paired albums of Kid A and Amnesiac. More traditional art museums have a similar lack of explanation or education about their works, simply displaying each piece with its title and author, much like Kid A Mnesia has. Despite its video game-based idiosyncrasies, Kid A Mnesia truly does seem to function as a museum.

Video games also have the potential to serve as tools of learning beyond just mimicking museums. After all, games are already primed to teach— it is impossible to pick up a new game without, in some manner, the game teaching its players new mechanics. (Anderson, Sky LaRell. “The Interactive Museum: Video Games as History Lessons through Lore and Affective Design.” E-Learning and Digital Media 16, no. 3 (2019): 177–95. https://doi.org/10.1177/2042753019834957.) This also extends to a game’s lore— that is, the history of its world. Take, for example, Dark Souls III, a notoriously difficult action role-playing by studio From Software. Beyond being difficult, the Dark Souls series is known for having lore that players need to work to learn about, spawning droves of YouTube accounts dedicated to learning about the games’ worlds. The similarities to real-world history are easily apparent.

Much of the lore in Dark Souls III comes from the descriptions of various in-game items. As these descriptions are some of the only ways of learning the history of the game’s world, dedicated players spend great amounts of time delving into the descriptions. Valorheart, a combination sword and shield, is no exception, as its description sheds light on some minor aspects of the game’s world:

Weapon once wielded by the Champion of the Undead Match. A

special paired set consisting of a broad sword and a lion

shield.

The champion fought on, without rest, until he lost his mind.

In the end, only his page and a lone wolf stayed at his side.

(Miyazaki, Hidetaki, dir. 2016. Dark Souls III.

Bandai Namco Entertainment.)

Much can be gleaned from just this short description. First, whatever society this Champion belonged to used to value gladiatorial combat between various undead people and was structured enough to have pages— that is, knights’ assistants. Additionally, it may have viewed the lion as an important symbol, given its presence on Valorheart’s shield.

While it of course has its differences, this process is not dissimilar to real life history. Players and historians both have to make inferences about past societies using only what these cultures left behind, whether it be real, written accounts or fictional item descriptions. Dark Souls III is by no means an educational title, but it shows how games can be used to teach. This goes beyond just self-identified educational games, as those “tend to be boring, monotonous, and frankly not very well-designed visually, mechanically, or even pedagogically.” (Anderson, Sky LaRell. “The Interactive Museum: Video Games as History Lessons through Lore and Affective Design.” E-Learning and Digital Media 16, no. 3 (2019): 177–95. https://doi.org/10.1177/2042753019834957.) Video games already have the capability to absorb players for potentially hours, something which traditional methods of education rarely are able to do.

Games cannot, of course, outright replace traditional methods of education like classes or textbooks. Instead, they can function as methods of “tangential learning,” in which the education takes place in the background, almost unnoticed, while the main focus for the player is the game itself. (Anderson, Sky LaRell. “The Interactive Museum: Video Games as History Lessons through Lore and Affective Design.” E-Learning and Digital Media 16, no. 3 (2019): 177–95. https://doi.org/10.1177/2042753019834957.) Video game developers have already mastered using tangential learning to teach players about their game’s lore without taking them out of the play experience, a technique which could easily be used for real-world education.

In their individual ways, LSD: Dream Emulator, Kid A Mnesia Exhibition, and Dark Souls III each showcase the benefits— and potential pitfalls— of video games as museums. LSD is perhaps the least museum-esque of the three, but it serves as an example of video games as art. Like some museums that lack interpretative labels, the game leaves its players (or perhaps viewers) to interpret the art for themselves, allowing them to each make their own distinct interpretations.

Kid A Mnesia most directly represents the visual design and visual language of museums. Radiohead was very interested in recreating the experience of going to a museum, while making use of the unique properties of video games to create an experience more abstract than would be possible with a real, brick-and-mortar museum. It also has the benefit of being much more accessible than physical museums; while it does require that players have a powerful enough computer to run the program and have a general knowledge of how to play first-person video games, anyone regardless of physical location is able to play the game. There are also fewer (although not zero) barriers with those with physical disabilities, as there are no possibilities of inaccessible bathrooms or lack of wheelchair-friendly ramps, for example.

However, Kid A Mnesia does not teach its players anything, at least not directly. Most art museums, at least American ones, have some interpretation. Labels explain the artist’s history or inspirations; text on the walls explains the overarching theme of an exhibit; docents answer visitors’ questions. The closest Kid A Mnesia comes to this is the very beginning of the game, where some text on a wall begins with modified lyrics from the band’s song “Pulk/Pull Revolving Doors” followed by this somewhat cryptic poem:

This begs the question: do museums need to be educational? Or is the presentation of art in an interesting manner enough? While Kid A Mnesia may at times look like a museum, calling itself an exhibition and providing a museum-esque map at a linked website, it often does not function like one. It intentionally dehumanizes every other person in the space, other “guests” and museum employees alike being rendered as simple stick figures. Instead, the game uses the design space of museums as background context to show the players its art and its music, less interested in pedagogy and more interested in evoking specific feelings.

On top of all of that, Kid A Mnesia does not make use of video games’ specific strengths as a medium; it uses its unreal location to be able to create impossible geometry and layouts, yes, but beyond that the experience is akin to that of going to a physical museum. While that was probably intentional, given the project’s initial roots as a real exhibit, video games are capable of providing learning experiences in manners wildly different from actual museums.

Unlike LSD Dream Emulator, which functions more like a piece of art than a game, and Kid A Mnesia, with its interest in the visual language of museums, Dark Souls III does not in any way try to mimic or recreate real-world art or museums. Despite this, it still manages to teach its players about its fictional setting in a manner potentially more effective and engaging than traditional classroom environments. What if, then, instead of video games mimicking museums, museums mimicked video games? In further exploration of this question, Seb Chan discusses Sleep No More, an immersive theater experience “loosely based on Macbeth [and] inspired by film noir.” (Chan, Seb. 2012. “On Sleep No More, Magic and Immersive Storytelling.” Fresh & New(Er) (blog). May 23, 2012.) In the video game-esque production, mask-clad guests freely wander the stage, gaining a highly unique and individualized experience.

Museums have always been wary of overly theatrical

experiences, lest they be labeled as “charlatans.” (Chan, Seb. 2012. “On Sleep No More, Magic and Immersive

Storytelling.” Fresh & New(Er) (blog). May

23, 2012.) But that attitude betrays museums’ nineteenth century

popular roots— roots of cabinets of curiosities and freak

shows (despite the unsavory nature of the name) advertising

wonders like “‘miracles of modern medicine…’ [and] freak

shows.” (Chan, Seb. 2012. “On Sleep No More, Magic and Immersive

Storytelling.” Fresh & New(Er) (blog). May

23, 2012.) Museums could have a lot to gain from interactive

experiences like Sleep No More or video games writ large.

To break the veil of academic professionalism, some of my

recent favorite museum experiences have come from heavily

interactive exhibits. Planet Word, a linguistics-focused

museum in Washington, D.C., has several very interactive

experiences. (‘Planet Word.’ Planet Word Museum. Accessed November

23rd, 2023.

https://planetwordmuseum.org/) These range from a collaborative lesson with a computer

about English etymology to helping an artificial intelligence

workshop its jokes. While not on the same level of

interactivity as Sleep No More, Planet Word’s

exhibits show how much more engaging non-linear, personalized

experiences can be. As a college linguistics major, I hardly

learned anything at Planet Word, but I nevertheless found it

all incredibly fun. Working with a group of fellow guests

trying to guess the language of origin of “shampoo” (Hindi)

was a more memorable experience than simply reading some text

on a wall discussing the origins of the word.

As the world continues to further digitize, museums need to digitize with it. Although I will always love museums, ranging from the imposing federally funded affairs to the hyper-local, low budget exhibits, they can be intimidating and difficult to break into. I am not suggesting that museum docents should lead guests to a video game console and have that be the majority of the visit, but the inherent accessibility and individuality of game-like experiences should be considered. This could even be a step towards Marstine’s idealized “post museum,” a community-focused endeavor that aims not to simply collect and study but to engage with its visitors and local community on a more personal level.

Bibliography

- Anderson, Sky LaRell. “The Interactive Museum: Video Games as History Lessons through Lore and Affective Design.” E-Learning and Digital Media 16, no. 3 (2019): 177–95. https://doi.org/10.1177/2042753019834957.

- Chan, Seb. 2012. “On Sleep No More, Magic and Immersive Storytelling.” Fresh & New(Er) (blog). May 23, 2012.

- Duncan, Carol, and Alan Wallach. 1980. “The Universal Survey Museum.” Art History 3 (4): 448-69.

- ‘Exploratorium.’ Exploratorium. Accessed November 23rd, 2023. https://www.exploratorium.edu/

- Marstine, Janet. 2008. New Museum Theory and Practice: An Introduction. Newark: John Wiley & Sons, Incorporated.

- Miyazaki, Hidetaki, dir. 2016. Dark Souls III. Bandai Namco Entertainment.

- “Museum Definition.” n.d. International Council of Museums. Accessed November 9, 2023. https://icom.museum/en/resources/standards-guidelines/museum-definition/.

- ‘Museum of Reclaimed Urban Space.’ MORUS. Accessed November 23rd, 2023. http://www.morusnyc.org

- ‘Planet Word.’ Planet Word Museum. Accessed November 23rd, 2023. https://planetwordmuseum.org/

- Sato, Osamu, dir. 1998. LSD: Dream Emulator. Asmik Ace Entertainment.

- Yorke, Thom. 2021. Radiohead explain the story behind the creation of its Kid A Mnesia Exhibition, out today on PS5. Interview by Stanley Donwood. https://blog.playstation.com/2021/11/18/radiohead-explain-the-story-behind-the-creation-of-its-kid-a-mnesia-exhibition-out-today-on-ps5/.