Thanks to new technology and post-pandemic culture shifts in the way we engage with spaces in person and online, the demand for recreation of physical spaces on digital platforms for education and recreation has never been higher. Advances in photogrammetry technology and VR integration have created new possibilities for taking real objects and environments and recreating them in explorable digital spaces. Potentially a result of the COVID-19 pandemic, there is a strong desire for people to experience meaningful places, which is evident in the travel industry’s rebound as pandemic regulations lessened. People desire to return to spaces that bring comfort and meaning, as well as to experience things they could not during periods of closure. Those who can’t travel find other ways to engage with places they are nostalgic for, including through online communities or through materials produced by museums and historic sites. Audiences look for interesting ways to experience meaningfully designed spaces as they remember them through online formats, including through increasingly popular theme park attraction ride-through videos, virtual reality coaster ride simulators, and a wide range of virtual tours of museum exhibits and cultural heritage.

An exploration of nostalgia and how it pertains to preserving designed space inspired the following look at museums and virtual reality. While considering the benefits of digitizing existing exhibits for VR, I looked at the very active online fan communities that exist around theme parks. Despite their dedication being focused on for-profit parks and resorts, theme park fans go to great lengths to record, document, and digitize the histories of theme parks and attractions that currently stand or that have long since been demolished or modified. Rich, crowdsourced histories exist of Walt Disney World rides from development to demolition. Extensive, multi-POV ride through videos exist of attractions at parks all around the world for those who may not have the chance to visit them. Ambitious fans, such as those behind the Defunctland VR Project, have gone so far as to recreate entire ride experiences in VR so that fans can experience lost attractions in full detail once again. These projects are generated by themed entertainment audience members who long to capture the work that went into creating designed space and what it was like to experience said attraction firsthand. These audiences aren’t just a niche either—the Defunctland YouTube channel regularly nets millions of views on their extensively researched theme park history videos. Visitors feel a strong sense of attachment to themed entertainment settings, often strengthened by nostalgia for travel and for time spent with family. I often see discussions online from fan communities about theme parks, but rarely to the same degree about museums.

While theme parks and museums might not immediately seem tied closely together, they are both tourism destinations that are designed to intentionally immerse visitors in an environment where they are most receptive to the products or information shared within them. The Themed Entertainment Association recognizes the close interconnectivity and shared audiences of museums and theme parks for the tourism industry in the experience economy. In both worlds, visitors’ complete experiences are curated from entrance to exit to provide the best possible visit. Both sectors strive to make the experience of visiting memorable, unique, and distinct from other places to foster a relationship with the guest. Exhibits are designed to provide an environment that is complimentary to the content—whether that is through immersive exhibits in science museums or carefully curated spaces of reflection in art museums. Museum objects do not exist out of place, the space and presentation of how they are perceived are integral to the creation of memory and the overall experience of the visitor. Visitors will remember what’s meaningful because of the wholistic experience, not just the objects themselves.

Theme park enthusiasts work hard to document park experiences by sharing them while they are operational online for others to see, or by painstakingly recreating demolished attractions through photographs, video, and VR—largely because they know the park ownership will not. Rebecca Williams’ work on fandom culture around theme parks discusses that fan memorialization of theme park attractions may help provide a method of reassuring “ontological security” by allowing fans to re-articulate and re-explore their attachments to rides and exhibits and the associated memories tied to them. (Williams, Rebecca. Theme park fandom: Spatial transmedia, materiality and participatory cultures. Amsterdam University Press, 2020.) I believe that museum audiences are more like these theme park enthusiasts than we typically discuss, but have a different relationship of attachment to museums as sites to preserve—the obligation to preserve museum spaces and their history is not in the hands of fan-historians working against corporate ownership but instead is a role for museums themselves. Museums have a reputation of record keeping and preservation, and there is an expectation of diligence in documentation. When given ways to engage with museum exhibits past and present online, I believe museum audiences similarly re-explore their attachments in a way that fosters their positive relationship with institutions. Virtual reality, while primarily used for tours and outreach online for current exhibits, allows museums to create records of their exhibits that allow audiences to connect to their collections remotely or after exhibits close. Maintaining the emotional connection between visitors and exhibit spaces allows guests to explore feelings of nostalgia and wonder linked to spatial memory, helping encourage repeat visitorship, foster donor relationships, and maintain positive feelings about the institution.

Resources for creating Virtual Reality tours have become more accessible, creating new possibilities for how exhibits are documented and displayed online. Some museums, such as the National Museum of Natural History (NMNH) are ahead of the crowd with many virtual tours of exhibits past and present available on their website. Others have gone further and created exhibit experiences in third party game software. Still many other institutions have never considered creating VR versions of their exhibits and would not know where to begin. With the increasing pressure on museums to provide online resources, I believe that utilizing VR to document exhibits serves an important twofold function—it creates a means by which audiences can engage with the museum from home and it creates a record of the holistic experience of exhibitions that can be used by museum fans and museum academics when we discuss exhibit design.

Virtual Reality and Preserved Museum Spaces

The most widely used method of documenting real space in full is using 360° cameras. Utilized in industries such as house tours for real estate, mapping software, and in museums, 360° cameras capture the panoramic details of a location through photography. Typically done with omnidirectional cameras which capture a picture in every direction at the same time, panoramic images of spherical videos create a 3D effect without being 3D. These pictures can be shared as 2D images which can be navigated by scrolling or by following paths of associated images that have been connected. Commonly used services such as Google Photos and Facebook both have integration for sharing these types of panoramic images. They may also be captured for conversion for use in VR, which can provide a more organic way for viewers to explore the space. (Lafontant, Floris. “A Beginner’s Experience with 360° Photography in Museums and Art Spaces.” In Context RSS, October 2018. https://blogs.stthomas.edu/arthistory/2018/10/23/a-beginners-experience-with-360-photography-in-museums-and-art-spaces/.) Laser scanning technology is also utilized for capturing exhibits, although more expensive and therefore less often utilized in smaller institutions.

Museums are not strangers to using 360° cameras to document their spaces. The Renwick Gallery’s WONDER 360 app and website-integrated VR experience allows guests to explore gallery-sized installations celebrating the Renwick Gallery either through the browser view or through the app, which allows users to view the space in 3D using a VR viewer such as Google Cardboard. (Smithsonian American Art Museum. “Wonder 360: Experience the Renwick Gallery Exhibition in Virtual Reality.” Smithsonian American Art Museum. Accessed October 16, 2023. https://americanart.si.edu/wonder360.) The Louvre, the most visited museum in the world, provides seven galleries you can explore online. While their model does not allow as much freedom to zoom and explore the space, it still provides gallery credits and additional information about collections objects for viewers. The Rijksmuseum in the Netherlands offers both a standard virtual exhibit space with integrated audio tour elements and a version of the museum that features gamified elements focused on finding keys to encourage exploration of the collection online. (Rijksmuseum. “Rijksmuseum Masterpieces up Close.” Rijksmuseum.nl. Accessed October 16, 2023. https://www.rijksmuseum.nl/en/masterpieces-up-close.) While many of these tours are accessible from a phone or browser, some require technology such as an Oculus to view. Others rely on easily utilized platforms such as Google Streetview. Tragically, some virtual tours and experiences are hosted using Adobe Flash, which is no longer available on standard browsers after December 2020. While specialized browsers such as Puffin which have integrated Flash players still can run these tours, they are not accessible to the average visitor without clearing additional hoops.

The 2020 global pandemic acted as a catalyst for museums to evaluate their digital footprint as the world adapted to engaging with learning and culture through digital formats during lock down and subsequent periods of high-risk transmission. Museums who could not serve the public on-site needed to find ways to engage their audiences through other means, and more and more institutions took their first leap into utilizing technology to provide some kind of supplemental experience. While many museums opted to provide tours or programs facilitated through video format over zoom or through prerecorded tours, other museums with resources to do so chose to innovate using XR technology (a catchall term for Virtual Reality, Augmented Reality, and Mixed Reality experiences). (Gerencer, Tom. “What Is Extended Reality (XR) and How Is It Changing the Future?” HP® Tech Takes, April 20, 2021. https://www.hp.com/us-en/shop/tech-takes/what-is-xr-changing-world.) For some, this meant providing augmentation on-site to provide additional interpretation to exhibits, sometimes in-lieu of contact with educators. Other museums found ways to present their collections of objects online, often in blank-walled digital galleries.

These digital galleries, albeit useful for the museum to share their objects, may not integrate the thoughtful design of the exhibitions that objects are presented within. While this may work for certain types of collections such as art museums, it fails to provide the immersion of experiencing an exhibit in-context and does not create the nostalgic triggers associated with seeing a work of art or exhibit in the context of the museum space itself. This may lead to less association between the viewer and the museum, as opposed to just the object being presented. However, the blank-walled VR rooms provide a fast way for museums to present art in explorable space next to other associated works, likely saves work hours and design costs to create, and do not require museums to purchase cameras needed for fuller capture of the exhibit environment.

Companies such as Vortic are looking to help solve the shortcomings of the white-walled digital exhibit experience. Vortic’s services work with museums and galleries to create VR recreations of exhibits which are hosted in Vortic’s engine and include exhibit texts, lighting design, and recreation of the actual architecture and design of the exhibits. These 3D environments are typically created by scanning gallery spaces to integrate into Vortic’s engine, and they boast custom photogrammetry technology to scan sculptural objects in detail. (Vortic. “For Institutions.” Vortic, July 4, 2022. https://partners.vortic.art/for-institutions.) Intuitive controls allow visitors to navigate the exhibits on their phones or computers with simple gestures, and additional information about objects and artworks can be added.

This technology has been utilized by institutions such as the Institute of Contemporary Art Boston, the MADC Museo de Arte y Diseño in Costa Rica, the Museum of Contemporary Art Detroit, and the Wallace Collection in the United Kingdom. These VR experiences allow museums to provide online experiences for actively running exhibits, as well as preserve an online archive of past exhibits. The digitization of the exhibit in full context helps maintain the museum’s ownership of the space and content in our associated memory. Vortic’s platform also provides institutions the ability to host meetings, tours, and events in their VR spaces, which helps transform their VR exhibit environments from stagnant recreations of a floor plan to settings that can be alive, discussed, and experienced. Despite the convenience of Vortic’s services, the potentially expensive per-month hosting and usage costs may prevent smaller institutions from utilizing the platform for their exhibits.

Other companies such as

Matterport

provide cheaper services, most often used for commercial

real-estate projects, to create ‘digital twins’ of spaces. The

National Gallery of Art utilized Matterport when creating the

virtual tour of

Raphael and His Circle, which opened at the NGO right as the COVID-19 pandemic

struck in early 2020.

National Gallery of Art. “Raphael and His Circle Virtual

Tour.” Raphael Virtual Tour. Accessed November 24, 2023.

https://www.nga.gov/features/raphael-virtual-tour.html.

Mused, which focuses on sharing virtual cultural heritage sites

through 3D guided tours and recreations, demonstrates how that

technology can be integrated with interest points which allow

guests to explore key spots and objects in a historical site

or historical house setting, which might not be ideal spaces

for the standard model of recreating space in 3D “rooms”.

Mused Team. “How to Build a Digital Exhibition for Your

Museum or Heritage Site in 2022: Getting Started, Part 1

of 3.” Mused. Accessed October 16, 2023.

https://blog.mused.org/how-to-build-a-digital-exhibition-for-your-museum-or-heritage-site-in-2022/.

Pushing the technology still further, photogrammetry

technology can go so far as to recreate cultural heritage

sites and outdoor landscapes in order to document spaces at

risk of natural erosion or decay from the elements or other

human factors like damage in conflict. (Cornwall Museum Partnership. “Coastal Timetripping

Launch.” YouTube, May 17, 2021.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ERQMKhQy1pI.)

The VR format allows museums to preserve more than just the spatial details of exhibits. As demonstrated thorough the Los Angeles Museum of Art’s Substrata virtual exhibit hosted on the digital exhibition platform EPOCH, exhibits can integrate audio and ambiance into the experience of viewing. Just as museums are not spaces void of noise, music, and designed sound in person, digital exhibits can also integrate audio into the experience. Not only does this more closely mimic the experience a visitor might have while viewing an exhibit and therefore more likely trigger associated feelings of nostalgia, but it also offers a place for the soundtracks designed for museum settings to continue to live on past the exhibit’s in-person lifespan. Unsettled, an exhibition created by the Australian Museum, integrates audio that is key to the visitor experience in-person into their virtual tour. In doing this, the virtual experience becomes closer to the in-person experience and creates a space where the compositions made for the exhibit continue to serve their purpose.

VR Museums in Game Spaces

Recently, museums have begun to recognize the value of partnering with video game companies to reach broader audiences. Platforms such as Roblox, VR Chat, Second Life, and Sansar provide existent platforms to host exhibits and collaboration events within. This has certain benefits—these platforms already have existing audiences that the museum can draw from to expand viewership. They may already have integrated creator tools and assets that make the process of setting up the exhibit faster or more streamlined. Partnerships with platforms benefit both parties and may help cut costs of development or provide free advertising for the partnering museum. However, it also has downsides. Although true of most software that is not developed in-house, there is no guarantee of the lifespan of the platform hosting the virtual exhibit. Ownership of companies, hosting costs, and collaborator interests all mean that there is no guarantee that a digital exhibit created in these spaces will have longevity. While innovative, game platforms can be a risky place for museums to invest all their VR resources.

One example of this is the VR exhibit companion to the Smithsonian American Art Museum’s (SAAM) No Spectators: The Art of Burning Man exhibit, which was open from March 2018 to January 2019. (Pangburn, DJ. “How the Smithsonian is turning its art exhibitions into virtual reality.” 2018. https://www.fastcompany.com/90213035/how-the-smithsonian-is-turning-its-art-exhibitions-into-virtual-reality-experiences.) The exhibit required 12,490 photos to generate the 3D models and a total of 1,050 labor hours to create the VR ready models. This exhibit provides immaculate renderings of the artworks on display, as well as the associated lighting design and sound that complimented them. (Bonasio, Alice. “Experience the Art of Burning Man in Vr.” VRScout, July 30, 2018. https://vrscout.com/news/experience-art-of-burning-man-vr/.) However, it requires users to download the Sansar software and utilize a VR headset to access, which creates a smaller audience pool than if hosted on the SAAM site.

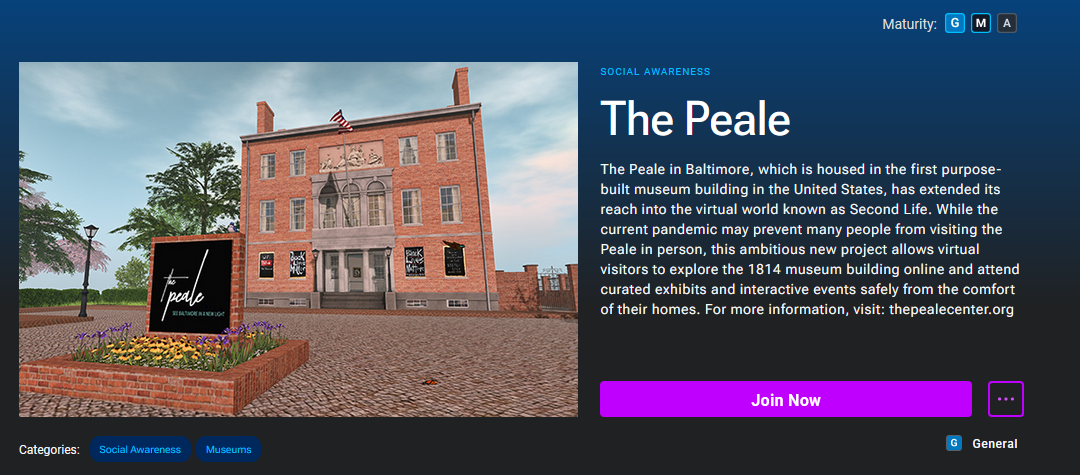

A successful integration of a museum in a game setting is the digital version of The Peale Center for Baltimore History and Architecture in Second Life. Over the pandemic, the Peale collaborated with Linden Labs, the company behind both Second Life and Sansar, to recreate the Peale and its exhibits on the platform. This undertaking had twofold purposes—to allow visitors to continue to access the Peale and its collections from home, as well as to allow the staff and museum collaborators to meet in a setting that allowed them to better activate their connection to the museum while working remotely. This connectivity to the museum site helped keep staff enthusiastic and connected to the collection and helped them better understand their space so they could develop projects even while away. The virtual Peale became both a meeting space and an extension of Peale’s mission. (Parsons, Matthew. “How Virtual Platform Second Life Kept This Small Baltimore Museum Going.” Skift, November 24, 2020. https://skift.com/2020/11/24/how-virtual-platform-second-life-kept-this-small-baltimore-museum-going/.)

Hosting exhibits in game platforms allows virtual visitors more expression, more movement, and often more detail. However, the game element can also be a hindrance to the goal of the content. Because it is hosted in Second Life, which offers robust player avatar customization, the virtual Peale is no stranger to player avatar attire not suitable for a museum setting and had to create a dress code for the online space. Similarly, player behavior can be unpredictable in any type of game. Fortnite’s virtual Holocaust Museum specifically has paired down game-play features and disabled emotes to preserve the respectful tone of the exhibit experience—a lesson that was learned from rowdy player behavior at the virtual Martin Luther King experience hosted before. (Gilliam, Ryan. “Fortnite’s MLK Event Is a Weird Way to Hear the ‘I Have a Dream’ Speech.” Polygon, August 26, 2021. https://www.polygon.com/fortnite/22642844/fortnite-mlk-march-through-time-event.) The tone and typical audience of a game will affect who interacts with VR exhibits and how, and museums should consider this when choosing the platform to develop for.

Archiving Designed Space For Museum Scholars

I believe there is value in documenting exhibit design for educational and evaluative purposes for the museum field. Operating with limited budgets, it’s understandable that museums taking the effort to digitize exhibits for the sake of the museum field can be seen as self-serving. But as a graduate student, I have had many moments during research where I desperately wished I could see exhibits that are no longer standing to answer questions about how artifacts or theming were presented in-context, how guests navigated spaces and if they were accessible, or simply about how an exhibit on a topic was handled by a museum. For academics who want to innovate in the museum field, it feels remiss the documentation of exhibits in-full is something that’s not more widely done. Museum’s self-presented exhibit archives online are often simple splash pages about what existed before-- occasionally, the more detailed include installation photos or collection details. I am always thankful when a virtual tour is available when researching museums, allowing me to compare content even when I don’t have the privilege to see a site in person.

A resource that made me consider the value documentation of past exhibits is Zoolex. Created by the Zoo Design Association, Zoolex collects museum-submitted profiles about zoo and aquarium habitats around the world. The database provides information about zoo design, displays innovations in exhibit design through photograph documentation and exhibit layout drawings, and even provides climate data about the environmental conditions of the habitat. Created as the result of Monika Ebenhöh’s thesis “Improvements in Zoo Design by Internet-Based Exchange of Expertise”, Zoolex acts as a resource for zoo designers and caretakers. (Ebenhöh, Monika. “Improvements in Zoo Design by Internet-Based Exchange of Expertise.” Masters diss. University of Georgia, 1992.) I yearn for a similar multi-institutional database for exhibit designers in the broader field. While Zoolex does not provide fully digitized exhibit layouts, the photo documentation alongside design information is an excellent for visualizing space for those researching their exhibits. What would a multi-institutional database for past exhibits look like and could it be viable? That’s hard to say—the audience could be niche, and like Zoolex, museums would need to opt into summitting their own gallery tours or images. However, it would be an amazing resource to have the ability to search exhibitions up by topic to compare how they were handled at institutions around the world and across time, allowing designers to be inspired by what has come before, double check their own work for accidental plagiarism from exhibits they saw before but may have forgotten, and to compare how the same topic might be exhibited to different audiences globally.

Some institutions like the National Museum of Natural History have established digitization resources, such as the team they dub the “Laser Cowboys”. The Laser Cowboys of the Smithsonian Digitization Program Office’s 3D lab use laser scanners to document exhibitions, such as the massive Fossil Hall before it’s renovation in 2014. During that project, “cowboy” Adam Metallo said: “The main purpose of 3D scanning an exhibit like this is to have an archive of what an exhibit of this era might have looked. This is a documentation for folks in the future to know what a museum experience here was like.” (Smithsonian Magazine. “A Night at the Museum with the Smithsonian’s Laser Cowboys.” Smithsonian.com, April 23, 2013. https://www.smithsonianmag.com/smithsonian-institution/a-night-at-the-museum-with-the-smithsonians-laser-cowboys-39683076/.) Their team recognizes the value not only of digitizing objects for public access, but for documenting how the exhibit’s design and context might be useful for designers and academics in the future. While it can sometimes be hard to justify the time and cost of digitization, the archival value to the museum field is immense. It is my hope other museums who have the resources to will also choose to document their exhibits for this reason, especially ones that have such high visitation or cultural impact such as NMNH.

Barriers to Creating VR Exhibits

While it would be amazing if every museum could digitize their exhibits, the reality as discussed is that there are many barriers to undertaking VR projects. While not every 3D digitization project requires thousands of man-hours of work to complete, they do all require some level of flexibility by staff to take time, usually before or after operational hours, to do the manual work of photographing or laser-scanning the space. Most institutions do not have a team already trained in photogrammetry technology, let alone in creating digital programming, so time and financial resources are required to train staff and purchase equipment or to hire external contractors to complete the project. Even after the work of scanning is completed, the institution then needs to host, publish, or save the files for present or future use, which requires the digital resources to do so. For institutions who choose to partner with platforms like VR Chat or Second Life, there must be staff available to manage the relationship with the software and who can integrate the exhibit materials onto the platform. These skills don’t come overnight, especially for museums who have yet to adopt newer technologies. The output of a virtual tour may require an entirely new staff role (or more) just to get off the ground.

Outside of just the startup costs involved in taking on VR projects, the longevity of VR exhibits once published is also uncertain. Unless a museum has a robust team dedicated to digital projects already, they are likely relying on outside parties when hosting and creating their VR exhibits. Whether this is through services such as Google, Second Life, or Matterport, there needs to be somewhere to put the digitized exhibit so that visitors can interface with it. While companies expect their continued lifespans, the retirement of the widely used Adobe Flash highlights that something that is expected to be lasting and easy to integrate onto a web platform isn’t necessarily going to stick around. Virtual exhibits created on third-party platforms have an uncertain fate if companies like Matterport or Vortic close. Could the museum reuse the scans on another platform, especially if they used proprietary scanning techniques during the image collection process? Are there ways for the museum to keep versions of the tours that don’t require any specific software? These are questions to consider when we think about the fate of digital exhibits that exist now. The National Museum of Natural History supports the future of their digital exhibit tours by working with virtual reality artist Loren Ybarrondo, who coded their virtual tours in HTML5 and JavaScript for specific use by the institution, meaning no additional software is required to host. (Ybarrondo, Loren. “Loren Ybarrondo: Create Immersive Experiences with Virtual Reality.” Visual Construction. Accessed November 24, 2023. https://visualconstruction.com/index.html#home.) As a large institution who has committed resources for their VR projects, their budget allows for commissioned coding. But other institutions may not have the same ownership of their work and could grapple with hosting issues in the future.

For smaller museums just trying to get a VR project off the ground, uncertain hosting futures and usage rights can make planning difficult. To help alleviate some of the resource strain on museums starting up VR projects, Google Arts & Culture has initiatives and funding to provide different kinds of 3D digitization services for free, and host VR tours of museums and cultural sites on their platform. Partnering with Google reduces the work on the museum teams themselves, but comes with the complications of partnering with a massive company that comes with its own corporate complications about access, usage rights, user data, and funding that not every institution is willing to sacrifice on.

Not every museum is likely to be sold on the pitch of 3D digitization of exhibits. Some might value the temporal nature of exhibitions and prefer to let them exist and then pass as part of their process. Other museums may be protective of their materials such as architectural details, lighting design, or the artworks shown inside an exhibit. Some museums may fear that a digital version of an exhibit will dissuade in-person visitation. Artist’s usage rights might control the digital use of their works, which may prevent inclusion in VR exhibits. Anything from the unwillingness to use budget resources to a distrust of digital platforms could act as a barrier. For those who have already undertaken VR exhibit efforts, there is also the possibility of discouragement – a first VR exhibit experience might have been costly and time consuming while learning the ropes, which may put teams off from continuing to digitize more. Teams must grapple with where to invest resources if VR exhibits aren’t getting the outreach draw that were expected, even if the end product is impressive and archivally useful.

The pitch to executives and donors to invest resources in digitization can be difficult. Even the purest academic value of preservation of exhibits for the museum field is unlikely to be enough to sell VR exhibits to those who don’t see the immediate value. But as discussed when considering audience nostalgia of exhibits and attractions, there are ways to articulate the value of digitized spaces that serve many museum’s goals of legacy, audience retention, and outreach. Pushing past the novelty of the medium can be difficult, but a thoughtful argument can express how preserving exhibit spaces benefit museum audiences past, present, and future. Museums audiences are fan-bases, and just like nostalgic theme park fans, they want to feel connected with places they associate with recreation, learning, and family. Museums can take ownership of their body of exhibition work and their own nostalgic legacy by creating VR exhibits for their audiences that help them remember, connect, and continue to learn even long after an exhibit has been taken down. By doing so, they can control their relationship to their audiences now, and to audiences in the future looking back at what once was.

Bibliography

- Bonasio, Alice. “Experience the Art of Burning Man in Vr.” VRScout, July 30, 2018. https://vrscout.com/news/experience-art-of-burning-man-vr/.

- Cornwall Museum Partnership. “Coastal Timetripping Launch.” YouTube, May 17, 2021. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ERQMKhQy1pI.

- Ebenhöh, Monika. “Improvements in Zoo Design by Internet-Based Exchange of Expertise.” Masters diss. University of Georgia, 1992.

- Gerencer, Tom. “What Is Extended Reality (XR) and How Is It Changing the Future?” HP® Tech Takes, April 20, 2021. https://www.hp.com/us-en/shop/tech-takes/what-is-xr-changing-world.

- Gilliam, Ryan. “Fortnite’s MLK Event Is a Weird Way to Hear the ‘I Have a Dream’ Speech.” Polygon, August 26, 2021. https://www.polygon.com/fortnite/22642844/fortnite-mlk-march-through-time-event.

- Lafontant, Floris. “A Beginner’s Experience with 360° Photography in Museums and Art Spaces.” In Context RSS, October 2018. https://blogs.stthomas.edu/arthistory/2018/10/23/a-beginners-experience-with-360-photography-in-museums-and-art-spaces/.

- Mused Team. “How to Build a Digital Exhibition for Your Museum or Heritage Site in 2022: Getting Started, Part 1 of 3.” Mused. Accessed October 16, 2023. https://blog.mused.org/how-to-build-a-digital-exhibition-for-your-museum-or-heritage-site-in-2022/.

- National Gallery of Art. “Raphael and His Circle Virtual Tour.” Raphael Virtual Tour. Accessed November 24, 2023. https://www.nga.gov/features/raphael-virtual-tour.html.

- Pangburn, DJ. “How the Smithsonian is turning its art exhibitions into virtual reality.” 2018. https://www.fastcompany.com/90213035/how-the-smithsonian-is-turning-its-art-exhibitions-into-virtual-reality-experiences.

- Parsons, Matthew. “How Virtual Platform Second Life Kept This Small Baltimore Museum Going.” Skift, November 24, 2020. https://skift.com/2020/11/24/how-virtual-platform-second-life-kept-this-small-baltimore-museum-going/.

- Rijksmuseum. “Rijksmuseum Masterpieces up Close.” Rijksmuseum.nl. Accessed October 16, 2023. https://www.rijksmuseum.nl/en/masterpieces-up-close.

- Smithsonian American Art Museum. “Wonder 360: Experience the Renwick Gallery Exhibition in Virtual Reality.” Smithsonian American Art Museum. Accessed October 16, 2023. https://americanart.si.edu/wonder360.

- Smithsonian Magazine. “A Night at the Museum with the Smithsonian’s Laser Cowboys.” Smithsonian.com, April 23, 2013. https://www.smithsonianmag.com/smithsonian-institution/a-night-at-the-museum-with-the-smithsonians-laser-cowboys-39683076/.

- Vortic. “For Institutions.” Vortic, July 4, 2022. https://partners.vortic.art/for-institutions.

- Williams, Rebecca. Theme park fandom: Spatial transmedia, materiality and participatory cultures. Amsterdam University Press, 2020.

- Ybarrondo, Loren. “Loren Ybarrondo: Create Immersive Experiences with Virtual Reality.” Visual Construction. Accessed November 24, 2023. https://visualconstruction.com/index.html#home.