Today, artificial intelligence (AI) is everywhere. With the creation of Siri, Alexa, and other virtual command search engines, we can engage with information in a more interactive and interpersonal way. An extension of this development is generative artificial intelligence, or generative AI, which the World Economic Forum defines as “artificial intelligence (AI) that uses machine learning algorithms to create new content in the form of images, text, audio, and more” (Routley, Nick. “What is Generative AI? An AI explains.” World Economic Forum, February 6, 2023. Accessed October 2, 2023. https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2023/02/generative-ai-explain-algorithms-work/). Another term used often with generative AI is large language modules, or LLMs, which exist as an umbrella term for all machine learning platforms that use large quantities of memory from a data source to output information (Riedl, Mark. “A Very Gentle Introduction to Large Language Models Without The Hype.” Medium. April 13, 2023. Accessed November 24, 2023. https://mark-riedl.medium.com/a-very-gentle-introduction-to-large-language-models-without-the-hype-5f67941fa59e#:~:text=As%20of%20the%20time%20of,for%20Generative%20Pre%2Dtrained%20Transformer). Companies like Open AI have developed some of the largest LLMs, such as ChatGPT, GPT-3, and DALL-E (Riedl, Mark. “A Very Gentle Introduction to Large Language Models Without The Hype.” Medium. April 13, 2023. Accessed November 24, 2023. https://mark-riedl.medium.com/a-very-gentle-introduction-to-large-language-models-without-the-hype-5f67941fa59e#:~:text=As%20of%20the%20time%20of,for%20Generative%20Pre%2Dtrained%20Transformer). These Generative Pre-Trained Transformers (Riedl, Mark. “A Very Gentle Introduction to Large Language Models Without The Hype.” Medium. April 13, 2023. Accessed November 24, 2023. https://mark-riedl.medium.com/a-very-gentle-introduction-to-large-language-models-without-the-hype-5f67941fa59e#:~:text=As%20of%20the%20time%20of,for%20Generative%20Pre%2Dtrained%20Transformer) utilize trained data to complete a variety of tasks, from developing project ideas to drafting entire dissertations.

Consider this trial session with ChatGPT 3.5, for example, in helping me brainstorm topic ideas for “Museums and Technology.” Within my search, I received insight on 18 different topics, ranging from virtual reality (VR) to QR codes, covering several topics we have discussed in class. (Disclaimer: The following questions have been edited to fit a website-friendly format, and I provided five of ChatGPT’s replies verbatim).

Emma Meverden: ChatGPT, help me brainstorm project ideas for museums and technology.

ChatGPT: Certainly! Here are some project ideas that combine museums and technology:

- Augmented Reality (AR) Exhibits: Develop AR applications that visitors can use on their smartphones or AR glasses to enhance their museum experience. For example, visitors could point their devices at an exhibit, and AR could provide additional information, animations, or 3D models related to the artifact.

- Virtual Reality (VR) Tours: Create immersive VR experiences that allow visitors to explore historical sites or exhibitions from the comfort of the museum. This can be particularly beneficial for museums with limited physical space.

- Interactive History Apps: Develop mobile apps that offer self-guided tours of the museum with interactive features like quizzes, challenges, or location-based puzzles that help visitors learn about history and artifacts in a fun way.

- AI-Powered Museum Guides: Implement chatbots or AI-driven virtual guides that visitors can interact with via a museum app or on-site kiosks. These guides can provide information, answer questions, and offer recommendations based on visitor preferences.

- Digital Art Installations: Collaborate with digital artists to create dynamic, interactive digital art installations that change in response to visitor input, creating a unique and evolving experience.

In another session, I asked ChatGPT to craft a poem in the spirit of John F. Kennedy. Not only did the software mirror historical allusions to the late president, including his famous quote “Ask Not What Your Country Can Do For You,” but it also wrote rhyming structures and an original title. (Disclaimer: Like the previous example, I modified my question to mirror the language in a web post. However, I provided the poem that ChatGPT generated verbatim.)

Emma Meverden: ChatGPT, how would John F. Kennedy recite a poem?

ChatGPT: Sure, here’s a poem in the style of John F. Kennedy:

“Ask not what your country can do for you, / But what you can do for your nation, it’s true. / In the face of challenges, we’ll stand strong, / For together, we’ll right what’s wrong. / From the moon to the stars, we’ll reach so high, / With courage and vision, we’ll touch the sky. / For America’s spirit is one of might, / Guiding us through the darkest night. / In the pursuit of justice, we’ll unite, / As we strive for a future that’s bright. / So let us be bold, let our hearts be free, / For in unity, we’ll find our destiny. / With hope in our hearts, we’ll always persist, / For in this great land, we shall coexist. / Ask not what your country can do for you, /But together, there’s nothing we can’t do.”

Whether with humorous user intention or not, generative AI has the potential to change how online users engage with people, learn new trends, and transform how we think about our routines and the world around us. Specifically, ChatGPT is beginning to transform the education sector, as teachers and professors are working to adapt to using (or prohibiting the use of) ChatGPT in their classrooms. As ChatGPT and other forms of generative AI become popular discussion topics within the legal and educational sectors, it has also become increasingly provocative within the museum sector. With these technological developments, a new question for studying and interpreting history is apparent: What if we used generative AI to transport us into the past? Within this think piece, I will explore the agency of historical figures in current museum exhibitions and inquire how museums take precautions with using AI.

Controversies and Criticism: AI in the Broader Cultural Heritage Sector

The question of authenticity and technology collaborating within a museum space predates the invention of generative AI. Specifically, conversations around “deep fakes” in museums have been around since at least the mid-2010s. For instance, scholars Jenny Kidd and Arran J. Rees write about AI within the greater humanities field, ranging from 3D prints of Rembrandt artworks to the generative artwork Portrait of Edmond Belamy selling for $432,500 in 2018 (Kidd, Jenny, and Arran J. Rees. “A Museum of Deepfakes? Potentials and Pitfalls for Deep Learning Technologies.” In Emerging Technologies in Museums, edited by Theopisti Stylianou-Lambert, Alexandra Bounia, and Antigone Heraclidou, 218-232. New York: Berghahn Books, 2022.). Just as the name suggests, the use of “deep fakes” employs a negative connotation. Some journalists have argued that AI perpetuates “fake news” and misinformation, especially when addressing AI-generated videos of using someone’s likeness to craft a false narrative (Kidd, Jenny, and Arran J. Rees. “A Museum of Deepfakes? Potentials and Pitfalls for Deep Learning Technologies.” In Emerging Technologies in Museums, edited by Theopisti Stylianou-Lambert, Alexandra Bounia, and Antigone Heraclidou, 218-232. New York: Berghahn Books, 2022.). These concerns transfer to the museum field, especially when expanding digital collections.

Generative AI has a controversial use case in nearly every industry, including the museum sector. While there has been discourse around chatbots in museums within the past decade, AI platforms like ChatGPT are a novelty in the museum sector, leaving much to be discovered. In some areas, ChatGPT excels, having passed national exams–including the US Medical Licensing Exam (Merritt, Elizabeth. “Chatting About Museums with ChatGPT.” American Alliance of Museums, January 25, 2023. Accessed October 27, 2023. https://www.aam-us.org/2023/01/25/chatting-about-museums-with-chatgpt/.). However, it does poorly in other areas, such as failing to accurately cite sources and its inability to perform simple mathematical problems (Merritt, Elizabeth. “Chatting About Museums with ChatGPT.” American Alliance of Museums, January 25, 2023. Accessed October 27, 2023. https://www.aam-us.org/2023/01/25/chatting-about-museums-with-chatgpt/.). With ChatGPT’s advancements in finding, analyzing, and generating text, many workers in writing-based careers are worried that the AI platform will replace them. Moreover, ChatGPT and other AI platforms have a track record of perpetuating racism and bias. In 2018, several users of the Google Arts and Culture app expressed disappointment when the app failed to match their selfie to a portrait who looked like them (Nuñez, Michael. “The Google Arts and Culture app has a race problem.” Mashable. January 16, 2018. Accessed November 23, 2023. https://mashable.com/article/google-arts-culture-app-race-problem-racist.). In particular, several people of color who used the app reported that the app matched them with a painting of an individual with a lighter skin tone or of European descent (Nuñez, Michael. “The Google Arts and Culture app has a race problem.” Mashable. January 16, 2018. Accessed November 23, 2023. https://mashable.com/article/google-arts-culture-app-race-problem-racist.). Racism and bias have also appeared in the medical field, as a Stanford study reports that chatbots like ChatGPT are perpetuating antiquated and racist ideas about Black patients when tasked to summarize doctors’ notes (Burke, Garance, and Matt O’Brien. “Health providers say AI chatbots could improve care. But research says some are perpetuating racism.” AP News. October 20, 2023. Accessed November 26, 2023. https://apnews.com/article/ai-chatbots-racist-medicine-chatgpt-bard-6f2a330086acd0a1f8955ac995bdde4d.).

In early 2023, the AI-powered app Historical Figures Chat raised controversy for its ability to converse with thousands of historical figures (Wu, Daniel. “AI chatbot mimics anyone in history — but gets a lot wrong, experts say.” Washington Post, January 31, 2023. Accessed October 20, 2023. https://www.washingtonpost.com/nation/2023/01/31/ai-gpt-chatbot-historical-figures/.). Developed by software engineer Siddhant Chadda, Historical Figures Chat allowed users to have conversations with any one of their 20,000 AI profiles of historical figures, ranging from Jesus Christ to Adolf Hitler (Merlan, Anna. “An AI Chatbot Connects You With Pol Pot, Jeffrey Epstein, and Jesus in the Afterlife.” Motherboard | Tech by Vice, Vice, January 19, 2023. Accessed November 24, 2023. https://www.vice.com/en/article/3ad9ww/an-ai-chatbot-connects-you-with-pol-pot-jeffrey-epstein-and-jesus-in-the-afterlife.). While the app had a disclaimer urging users to do their own fact-checking–stating that “‘A.I. is not guaranteed to be accurate–’” that did not stop educators from calling out alarming inaccuracies from these conversations. Zane Cooper, history teacher and researcher from the University of Pennsylvania, asked AI Henry Ford about his antisemitic views; specifically, Ford claimed his “reputation as an antisemite is based on a few isolated incidents” and, “in reality, [he] had many Jewish friends and associates.” (Wu, Daniel. “AI chatbot mimics anyone in history — but gets a lot wrong, experts say.” Washington Post, January 31, 2023. Accessed October 20, 2023. https://www.washingtonpost.com/nation/2023/01/31/ai-gpt-chatbot-historical-figures/.) Moreover, dictators like Heinrich Himmler and Pol Pot reportedly expressed remorse for spearheading genocide and other crimes against humanity. In falsely misrepresenting genocidal dictators as remorseful for their crimes, the spectator’s experience holds greater weight than the historical accuracy of the app. In other words, the Historical Figures project has resulted in the questioning of AI algorithms in sympathizing with extremists and rewriting history. Following this scandal, Chadda claimed the app is “a work in progress” and needs more training to ensure it maintains historical accuracy (Wu, Daniel. “AI chatbot mimics anyone in history — but gets a lot wrong, experts say.” Washington Post, January 31, 2023. Accessed October 20, 2023. https://www.washingtonpost.com/nation/2023/01/31/ai-gpt-chatbot-historical-figures/.).

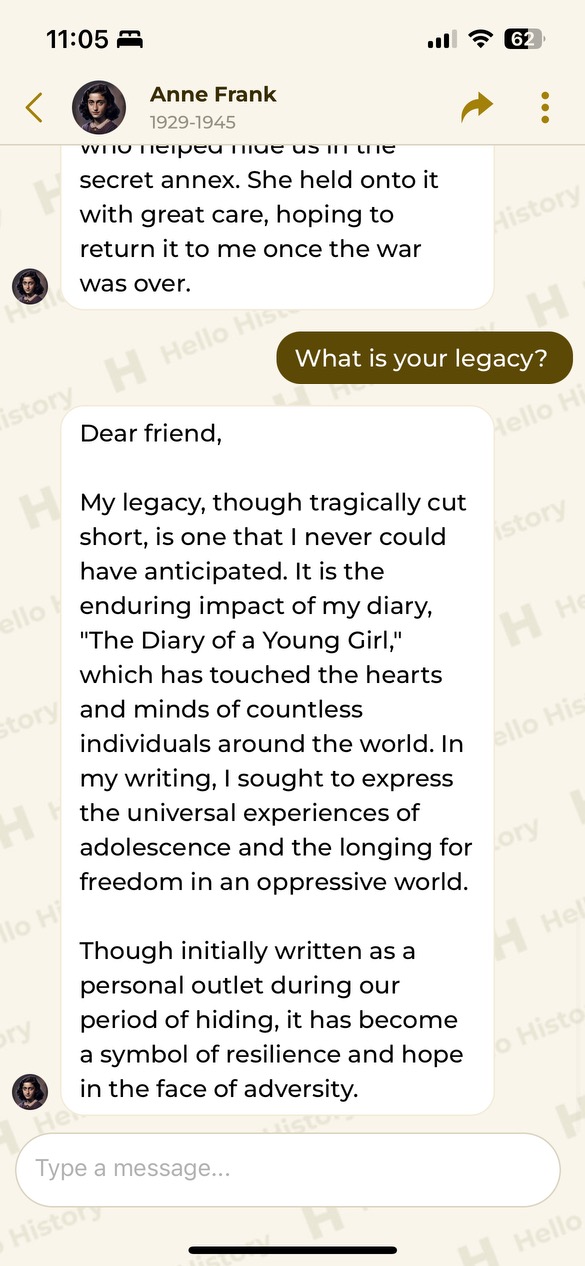

Can and should AI learning be used in this way if more research is needed on how the appliance retrieves information? What about other history-based AI apps? Can the same hold true for future trials of the same concept? I tested out another education-based app called “Hello History,” developed by another company called Humy (“For Education.” Hello History - Chat with AI Generated Historical Figures, 2023. Accessed October 4, 2023. https://www.hellohistory.ai/for-education.). Already, I could tell this app would be different because it is owned by a parent company that designs personalized AI assistants for smart device users. When I went to open the app, I looked to see who I could speak to. With nearly 400 historical figures to have conversations with, I did not find an AI version of Hitler, Pol Pot, or any notorious dictator. I decided to ask AI Anne Frank a few questions. Similar to Historical Figures Chat, Hello History warned me that the generated chat responses were “based on online historical information” and that “the responses may have biases and inaccuracies…please, verify facts” (“For Education.” Hello History - Chat with AI Generated Historical Figures, 2023. Accessed October 4, 2023. https://www.hellohistory.ai/for-education.).

I asked AI Anne Frank four questions. Each response I received was very academic and reflective in tone. For instance, when I asked AI Anne about her legacy, she responded the following about her famed diary: “Though initially written as a personal outlet during our period of hiding, it has become a symbol of resilience and hope in the face of adversity.”

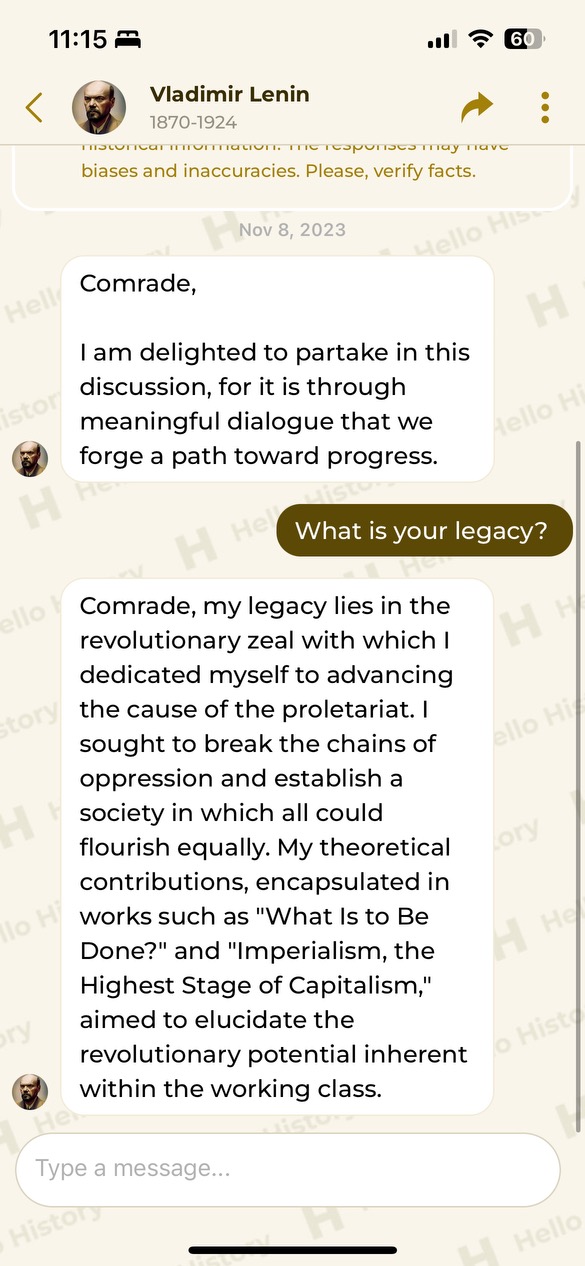

I then asked former Soviet ruler Vladimir Lenin the same question: “What is your legacy?” In his response, he stated that his legacy “lies in the revolutionary zeal with which I dedicated myself to advancing the cause of the proletariat.” When I asked about his views on the demise of the Russian Royal Romanov family, AI Lenin responded with the following: “[I]t remains a matter of debate as to what extent I personally advocated for their execution.”

Both AI Anne Frank and AI Vladimir Lenin’s responses appear to have a scholarly, yet neutral attitude. At the end of each session, I was left with questions on how Hello History narrowed down their data pool of information. Furthermore, how can this AI app be used to encourage younger generations to find the facts for themselves, and not solely rely on the word of the app?

AI and The Museum

In January 2023, Elizabeth Merritt of the American Alliance of Museums asked a series of questions about ChatGPT in ChatGPT, including how museums can best use the platform. ChatGPT responded with five viable options, including “creating exhibit labels, catalogs, and other educational materials” in the form of interactive Q&As and audio guides. These could serve as viable outlets for AI to offer assistance (Merritt, Elizabeth. “Chatting About Museums with ChatGPT.” American Alliance of Museums, January 25, 2023. Accessed October 27, 2023. https://www.aam-us.org/2023/01/25/chatting-about-museums-with-chatgpt/.).

Using AI platforms can provide a growth opportunity for museums, whether it be generating ideas for how to organize an exhibition or aiding in digital preservation. However, it is important to note that this product is only valuable when a human uses it. As Merritt poses the question of whether or not museum staff should use ChatGPT as a writing and research tool, she also asserts that human staff would need to be present to do fact-checking and assess the platform’s language. This shows that an AI platform cannot completely replace a human being’s work. Major institutions like the Smithsonian have incorporated values statements regarding their use of AI. While the Smithsonian embraces using AI tools to aid in the digitization and discoverability of historic materials and source communities online, the institution asserts it will only use technologies that respect its public and represent the values of its institution (“AI Values Statement.” AI Values Statement | Smithsonian Data Science Lab, 2022. https://datascience.si.edu/ai-values-statement.).

Humans designed AI systems; and just as we humans have our biases–unconscious and obvious–so do the systems we create. Like museums, technologies are not neutral.

Case Studies: AI Use of Historical Figures in The Dalí Museum and The United States Holocaust Memorial Museum

What are some ways that museums can use AI to represent history in their exhibitions? A possible answer can be provided in the tailored use of generative AI in the Salvador Dalí Museum and the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum (USHMM). In 2019, for instance, the Salvador Dalí Museum utilized DALL-E, “sibling” software to ChatGPT, to splice photos, videos, and recordings of Dalí’s mannerisms and vocal patterns to create a realistic likeness of the late surrealist painter (Salvador Dalí Museum. “Dalí Lives (via Artificial Intelligence).” Accessed September 17, 2023. https://thedali.org/exhibit/dali-lives/.). The staff behind this project shared how the digital projection of Dalí would create another avenue for visitors to explore Dalí’s creative mind and inspiration for his celebrated artworks. At the end of the exhibit, the AI-generated Dalí asks his visitors if they would like to take a picture with him, and he takes a selfie using a smartphone (Salvador Dalí Museum. “Dalí Lives (via Artificial Intelligence).” Accessed September 17, 2023. https://thedali.org/exhibit/dali-lives/.). In reality, Salvador Dalí would not have known what a smartphone was in his lifetime–let alone know how to take a selfie with one–as he passed away in the late 1980s. Therefore, is it wrong for the museum to share this minute inaccuracy about Dalí’s life? What other ramifications can historical AI figures bring?

Regarding the Dalí Museum, I was drawn to Hank Hine’s (Executive Director) emphasis on using AI Salvador Dalí to add another layer of empathy to the exhibit (Salvador Dalí Museum. “Dalí Lives (via Artificial Intelligence).” Accessed September 17, 2023. https://thedali.org/exhibit/dali-lives/.). In using Dalí’s mannerisms and stories of his life through the exhibit of his famous works, I can see how visitors would have a more nuanced understanding of Dalí’s creative vision. The desire for empathic reasoning and a dedicated mission to crafting accurate portrayals of a historical figure’s identity is commendable and should be the expectation within a museum setting. It is evident to me that the Dalí Museum has curated a version of Salvador Dalí that honors his artistic views and offers insightful commentary on his artwork.

Within the past three years, interactive AI has stirred controversy within museums and technology sectors. Jonathan Edelman wrote for Museums & Digital Technology in 2019 about digital testimonies incorporated in the USHMM. There, he shared how curator Heather Miao and staff from the Shoah Foundation Institute (SFI) and the USC Institute for Creative Technologies recorded testimonies of Holocaust survivors in response to questions visitors may ask when they arrive at the USHMM’s exhibition (Edelman, Jonathan. “Empathy + Technology: Digital Testimony in Holocaust Museums.” In The State of Museum Digital Practice in 2019: A collection of graduate essays and responses, by Suse Anderson, Cristin Guinan-Wiley, Jonathan Edelman, Rachel Rosenfeld, Mary McCulla, Sheridan Small, Cynthia Kurtz, Amy Pollard, Corrie Brady, Melissa Garcia, Caitlin Hepner, Sydney Thatcher, Laura Dickson, and Rebecca Brockette. Washington, D.C.: Ad Hoc Museum Collective, 2019. Accessed October 16, 2023. https://ad-hoc-museum-collective.github.io/GWU-museum-digital-practice-2019/essays/essay-1/.). It is also important to mention that three Holocaust survivors served on the board overseeing this project (Edelman, Jonathan. “Empathy + Technology: Digital Testimony in Holocaust Museums.” In The State of Museum Digital Practice in 2019: A collection of graduate essays and responses, by Suse Anderson, Cristin Guinan-Wiley, Jonathan Edelman, Rachel Rosenfeld, Mary McCulla, Sheridan Small, Cynthia Kurtz, Amy Pollard, Corrie Brady, Melissa Garcia, Caitlin Hepner, Sydney Thatcher, Laura Dickson, and Rebecca Brockette. Washington, D.C.: Ad Hoc Museum Collective, 2019. Accessed October 16, 2023. https://ad-hoc-museum-collective.github.io/GWU-museum-digital-practice-2019/essays/essay-1/.). Through this initiative, visitors can ask and actively converse with survivors about their lives before, during, and after the Holocaust. The answers are pre-recorded from living survivors, and docents are around to help visitors craft their questions. While this initiative brings an interpersonal layer to the exhibit, it also raises questions about the spectator being the main focus rather than the survivor’s experience.

While the USC Shoah Foundation and USHMM’s collaboration was very well received by scholars, journalists, and general museum-goers, the team was concerned about the project unintentionally making a spectacle out of this grave tragedy. However, as Stephen Smith (Executive Director of the USC Shoah Foundation) shared, the first group to participate in the project without question were the survivors themselves. Survivors gave their time and consent to answer over 2,000 questions, and for that, their memory will transcend their lifetimes and will be accessed by generations.

Both of the above exhibitions, while having their concerns, have a narrowly tailored focus on what hologram-like depictions can express in an exhibit that is reviewed by museum staff and third-party partners. Museums also have a plethora of resources–from digital catalogs to informational videos–which fosters a dynamic learning environment. As the Smithsonian’s AI Values Statement shares, it is imperative that the museum documents how its AI content is produced and for what purpose it serves (“AI Values Statement.” AI Values Statement | Smithsonian Data Science Lab, 2022. https://datascience.si.edu/ai-values-statement.). It also recommends frequent testing for bias and assessing how the bias aids the museum in its programming. Some central messages from the AI Values Statement are the need for continuous supervision of AI tools and clear distinction of when AI is used, for what reason, and where exactly it draws its data from (“AI Values Statement.” AI Values Statement | Smithsonian Data Science Lab, 2022. https://datascience.si.edu/ai-values-statement.). Unlike the museums, the AI app Historical Figures Chat drew input from all corners of the Internet, including divisive, discriminatory, and flamingly incorrect information, with very little sign of oversight from the app’s AI team. As Chadda previously shared, his product would be more successful if it had better training. Therefore, museums should follow the AI Values Statement in continuing to review the information they are inputting in their AI-generated initiatives and the legality of its use.

The Legality of AI

Generative AI is a new phenomenon in the legal field, especially concerning copyright law. Copyright law states that someone can be the sole owner of their work for the time of their lifetime plus 70 years after their death (Frank, Will. “IP-rimer: A Basic Explanation of Intellectual Property.” Medium, November 23, 2015. Accessed October 3, 2023. https://medium.com/@scifantasy/ip-rimer-a-basic-explanation-of-intellectual-property-9be6f0ce6711.). In a museum setting, could family or descendants have copyright over their ancestor’s image? According to the National Library of Medicine, only if the ancestor (especially if they were famous in their lifetime) has a current foundation and license to use their likeness (National Library of Medicine. “Copyright: Patron Guide to Copyright and Historical Materials.” Updated May 17, 2018. Accessed October 21, 2023. https://www.nlm.nih.gov/hmd/copyright/patron-guide-privacy-and-publicity-rights.html.). But, with so many famous artworks made by Dali or Van Gogh, all of their works are in the public domain.

Additionally, intellectual property claims–or, claims that focus on the legal protection of one’s ideas and creative work–can be poorly received in some cases. For example, if someone uses intellectual property law to censor someone’s criticisms of their work, then the courts will often rule against the plaintiff, or person who started the legal case (Frank, Will. “IP-rimer: A Basic Explanation of Intellectual Property.” Medium, November 23, 2015. Accessed October 3, 2023. https://medium.com/@scifantasy/ip-rimer-a-basic-explanation-of-intellectual-property-9be6f0ce6711.). With this legal observation, could some courts dismiss copyright claims to the portrayal of AI historical figures in museum exhibitions?

According to a Reuters report in August 2023, AI-generated art cannot be copyrighted, since it was not directly made by a human artist (Brittain, Blake. “AI-generated art cannot receive copyrights, US court says.” Reuters, August 21, 2023. Accessed September 29, 2023. https://www.reuters.com/legal/ai-generated-art-cannot-receive-copyrights-us-court-says-2023-08-21/.). With this knowledge in mind, would copyright laws impede a museum’s ability to use AI projections in future exhibitions? The United States Congress is assessing various arguments for and against the use of AI across the country (Zirpoli, Christopher T. “Generative Artificial Intelligence and Copyright Law.” Congressional Research Service: Legal Sidebar. Updated September 29, 2023. https://crsreports.congress.gov/LSB10922..). Many of these courts have argued that human authorship is necessary to file for a copyright claim. Without human beings to advocate for themselves, it appears that AI can be used to reconfigure a historical person’s likeness.

Moving Forward

AI is not going anywhere. It is not only beginning to hold influence in museums but the greater workforce and our legal landscape. Earlier this month in November of 2023, the SAG-AFTRA Union and the Alliance of Motion Picture and Television Producers (AMPTP) reached an agreement that studios must compensate and receive consent from the actor to allow generative AI to replicate their likeness (Klar, Rebecca. “SAG-AFTRA releases agreement, details AI protections.” The Hill. November 13, 2023. Accessed November 26, 2023. https://thehill.com/policy/technology/4307400-sag-aftra-releases-agreement-details-ai-protections/.). This case will likely help reinforce the precedent that consent is needed to generate AI based on a living person; however, the legality of using an AI replica of a deceased person is not always quite as clear.

AI is being explored as a tool for crafting an engaging visitor experience. However, there are ethical considerations that should be made when experimenting with AI. As code and algorithms are made by humans, they come with complexities that require human literacy and understanding. Technology can surprise machines and humans alike. As stated by museum experts Ariana French and Elena Villaespesa, the sector should establish clear expectations for how AI should be used in their museums and allocate their resources accordingly (French, Ariana, and Elena Villaespesa. “AI, Visitor Experience, and Museum Operations: A Closer Look At the Possible.” In Humanizing the Digital: Unproceedings from the 2018 MCN Conference,* First Edition*, 101-113. Middletown: DE: Ad Hoc Museum Collective, 2019.).

As the USHMM and the Dalí Museum illustrate, museums can use AI effectively if they can strategically tailor their programming to a specific language that holds the integrity of the history they are representing. In utilizing a cautious approach and scheduling frequent training sessions by staff and third-party vendors, AI can be used as a useful educational tool within the museum sector. However, with any new invention, it is essential the museum uses it often and with great review. When used with ethical consideration, AI can be a promising feature for new exhibitions. Museums should continue to use generative AI with great caution.

Bibliography

- “AI Values Statement.” AI Values Statement | Smithsonian Data Science Lab, 2022. https://datascience.si.edu/ai-values-statement.

- Brittain, Blake. “AI-generated art cannot receive copyrights, US court says.” Reuters, August 21, 2023. Accessed September 29, 2023. https://www.reuters.com/legal/ai-generated-art-cannot-receive-copyrights-us-court-says-2023-08-21/.

- Burke, Garance, and Matt O’Brien. “Health providers say AI chatbots could improve care. But research says some are perpetuating racism.” AP News. October 20, 2023. Accessed November 26, 2023. https://apnews.com/article/ai-chatbots-racist-medicine-chatgpt-bard-6f2a330086acd0a1f8955ac995bdde4d.

- Edelman, Jonathan. “Empathy + Technology: Digital Testimony in Holocaust Museums.” In The State of Museum Digital Practice in 2019: A collection of graduate essays and responses, by Suse Anderson, Cristin Guinan-Wiley, Jonathan Edelman, Rachel Rosenfeld, Mary McCulla, Sheridan Small, Cynthia Kurtz, Amy Pollard, Corrie Brady, Melissa Garcia, Caitlin Hepner, Sydney Thatcher, Laura Dickson, and Rebecca Brockette. Washington, D.C.: Ad Hoc Museum Collective, 2019. Accessed October 16, 2023. https://ad-hoc-museum-collective.github.io/GWU-museum-digital-practice-2019/essays/essay-1/.

- “For Education.” Hello History - Chat with AI Generated Historical Figures, 2023. Accessed October 4, 2023. https://www.hellohistory.ai/for-education.

- Frank, Will. “IP-rimer: A Basic Explanation of Intellectual Property.” Medium, November 23, 2015. Accessed October 3, 2023. https://medium.com/@scifantasy/ip-rimer-a-basic-explanation-of-intellectual-property-9be6f0ce6711.

- French, Ariana, and Elena Villaespesa. “AI, Visitor Experience, and Museum Operations: A Closer Look At the Possible.” In Humanizing the Digital: Unproceedings from the 2018 MCN Conference,* First Edition*, 101-113. Middletown: DE: Ad Hoc Museum Collective, 2019.

- Kidd, Jenny, and Arran J. Rees. “A Museum of Deepfakes? Potentials and Pitfalls for Deep Learning Technologies.” In Emerging Technologies in Museums, edited by Theopisti Stylianou-Lambert, Alexandra Bounia, and Antigone Heraclidou, 218-232. New York: Berghahn Books, 2022.

- Klar, Rebecca. “SAG-AFTRA releases agreement, details AI protections.” The Hill. November 13, 2023. Accessed November 26, 2023. https://thehill.com/policy/technology/4307400-sag-aftra-releases-agreement-details-ai-protections/.

- Merlan, Anna. “An AI Chatbot Connects You With Pol Pot, Jeffrey Epstein, and Jesus in the Afterlife.” Motherboard | Tech by Vice, Vice, January 19, 2023. Accessed November 24, 2023. https://www.vice.com/en/article/3ad9ww/an-ai-chatbot-connects-you-with-pol-pot-jeffrey-epstein-and-jesus-in-the-afterlife.

- Merritt, Elizabeth. “Chatting About Museums with ChatGPT.” American Alliance of Museums, January 25, 2023. Accessed October 27, 2023. https://www.aam-us.org/2023/01/25/chatting-about-museums-with-chatgpt/.

- National Library of Medicine. “Copyright: Patron Guide to Copyright and Historical Materials.” Updated May 17, 2018. Accessed October 21, 2023. https://www.nlm.nih.gov/hmd/copyright/patron-guide-privacy-and-publicity-rights.html.

- Nuñez, Michael. “The Google Arts and Culture app has a race problem.” Mashable. January 16, 2018. Accessed November 23, 2023. https://mashable.com/article/google-arts-culture-app-race-problem-racist.

- Riedl, Mark. “A Very Gentle Introduction to Large Language Models Without The Hype.” Medium. April 13, 2023. Accessed November 24, 2023. https://mark-riedl.medium.com/a-very-gentle-introduction-to-large-language-models-without-the-hype-5f67941fa59e#:~:text=As%20of%20the%20time%20of,for%20Generative%20Pre%2Dtrained%20Transformer

- Routley, Nick. “What is Generative AI? An AI explains.” World Economic Forum, February 6, 2023. Accessed October 2, 2023. https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2023/02/generative-ai-explain-algorithms-work/

- Salvador Dalí Museum. “Dalí Lives (via Artificial Intelligence).” Accessed September 17, 2023. https://thedali.org/exhibit/dali-lives/.

- Wu, Daniel. “AI chatbot mimics anyone in history — but gets a lot wrong, experts say.” Washington Post, January 31, 2023. Accessed October 20, 2023. https://www.washingtonpost.com/nation/2023/01/31/ai-gpt-chatbot-historical-figures/.

- Zirpoli, Christopher T. “Generative Artificial Intelligence and Copyright Law.” Congressional Research Service: Legal Sidebar. Updated September 29, 2023. https://crsreports.congress.gov/LSB10922..