X. Closing the Accessibility Gap: A Look at the Smithsonian Institution’s Use of Digital Technologies for Physically Impaired Visitors

- Megan Williams, The George Washington University

Digital technology continues to change year after year, with new technological innovations being continuously developed, re-imagined and applied to the museum field. With these changes comes the opportunity to implement digital technology to museum exhibitions, not only to make them more engaging, but to improve involvement with individuals who have hearing, mobility, or vision issues. For the purpose of this paper, digital technologies are defined as “electronic tools, systems, devices and resources that generate, store or process data.”1 Since the 1970s, museum professionals have been actively working on the betterment of engaging museum visitors who have disabilities.2 This movement forward is made evident by the American Alliance of Museums’ Diversity, Equity, Access and Inclusion webpage.3 This organization provides articles and resources that can be utilized by museums to aid their efforts in accessibility. Additionally, in their 2022-2025 strategic plan where they outline a projected framework to continue the furthering of diversity, equity, accessibility, and inclusion in the museum field.4

Following a similar route, the Smithsonian Institution has their own website dedicated to accessibility for museum professionals to use.5 This paper will focus on the Smithsonian Institution’s implementation of digital technologies to aid those with physical accessibility needs within in-gallery exhibitions. To be specific, the physical disabilities I will be covering here include visual, auditory and mobility issues. As a summation, I will discuss the challenges that come with adding digital technologies to museum exhibitions. These topics are of the utmost importance in the museum field, as we continue to work towards a more accessible and inclusive world for all.

Before continuing further, I wanted to add a short note regarding my position in this paper. Although I have no physical disabilities of my own, for the last ten years or so, a close family member has been living with severe mental and physical disabilities. Witnessing his experiences in museums and other institutions has shaped the way I approach this work. Professionals discuss the ideas of diversity, equity, and inclusion, but I feel it wasn’t until recently that accessibility was added to those ideas. While my paper is strictly on people with physical disabilities, I have seen an increase in accessibility for those with mental disabilities as well. It is there that my interest started with accessibility, especially within the museum profession. For my brother, and for many other individuals around the world, I want to create more inclusive access to museum spaces because people who are different have always been shuttered away from intellectual spaces. It’s time we open these spaces up for all and continue working towards more diverse settings everywhere.

History of ADA Compliance in Museum Spaces

In the summer of 1990, the first version of the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) was enacted by then President George H.W. Bush. The legislation of the ADA outlaws the discrimination of people with disabilities and affirms that they will “have the same opportunities as everyone else to participate in the mainstream of American life – to enjoy employment opportunities, to purchase goods and services, and to participate in State and local government programs and services”6. The United States Congress revised the Americans with Disabilities Act in 2008. Titles II and III were revised by the Department of Justice (DOJ) with regulations titled the 2010 ADA Standards for Accessible Design. These titles regard accessibility in public services and accommodations, as well as private services.7 Museums are covered under both of these titles depending on whether they are operated privately or publicly.8 As a federal institution, the Smithsonian Institution operates under Title II of the Americans with Disabilities Act.

Visual Accessibility Technologies within the Smithsonian Institution

Visual accessibility in museums focuses on the needs of expanding interaction to those who are blind or have low vision so that they feel more engaged and prioritized in the cultural space. In early 2019, the Smithsonian Institution began partnering with the visual interpreting service Aira Access to provide a free verbal description resource to each of their museums in Washington D.C. via the Aira app. The app can be downloaded to any museum visitor’s cellular device and the application will connect the visitor to trained real-time agents through the free Smithsonian Wi-Fi.9 This service allows visitors who are blind or have low vision to be independent and explore the museum at their own pace, as the Aira agent objectively describes the surroundings. By doing this, the agents act as the visitor’s eyes, while the visitor can create their own commentary of the objects and environment around them.10

In the National Museum of American History, raised wayfinding lines on the floor throughout varying galleries indicate the presence of QR codes that can be scanned by patrons. These codes bring the visitor to a Smithsonian website that is compatible with screen readers for visually impaired visitors to use to hear the information through their phone’s speaker or headphones. The information available through these QR codes include photos from exhibit cases, as well as similar text to those displayed on the walls of the exhibition. Additionally, the website provides instructions on how to navigate to more QR codes, as well as detailed descriptions of touchable objects scattered around the exhibit.

Also located in the National Museum of American History, is the Molina Family Latino Gallery. The Molina Family Latino Gallery is a prime example of a new exhibit space being designed for accessibility rather than around accessibility. The Smithsonian worked with Janice Majewski from the Institute for Human Centered Design to curate the gallery space for museumgoers with disabilities to “feel welcome rather than tolerated.”11 This is an important step forward in the world of accessibility and inclusion, especially since approximately 1 in 6 of the Latino community has a disability.12

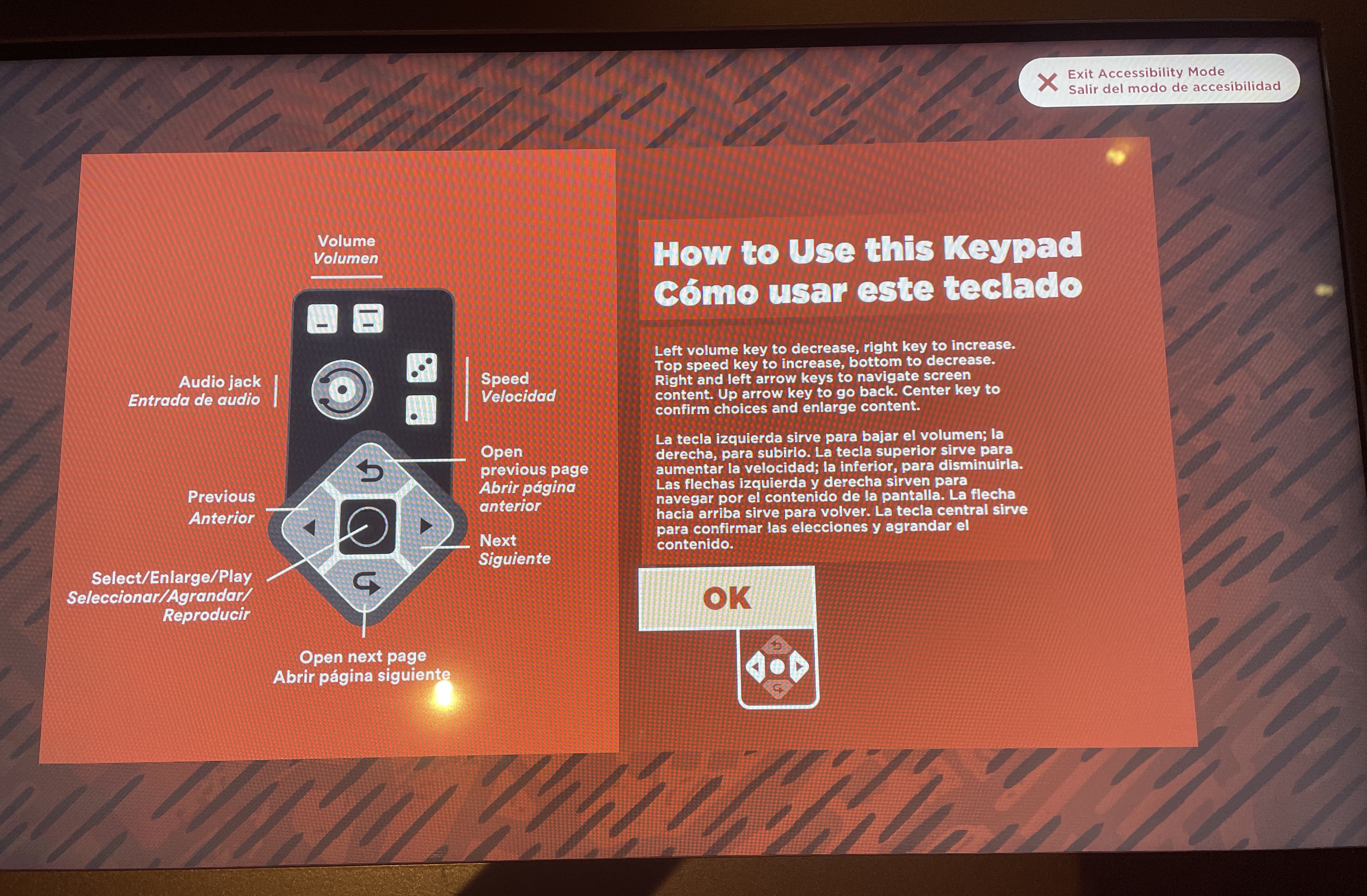

The QR codes mentioned earlier are also featured in this exhibit, with thirteen of them spread around the new space for visitors to scan. The gallery also features many digital screens that include keypads with braille on them for ease of use by those who are blind or have low vision.

Figure 1

Figure 1 Figure 2

Figure 2These digital screens and the keypads were designed as a way to permit each visitor with engaging with the exhibit. The Smithsonian worked alongside cultural accessibility consultant, Nefertiti Matos who is blind, to design the accessibility of the screens and its keypads functions.13 The keypads have plugs for wired headphones that visitors can either bring themselves or ask staff for. By doing this, visitors with low vision or who are blind, can navigate through the gallery space and listen to the artifact and display descriptions orally. As an addition to this exhibition space, the olfactory senses are a focus for all as well with three displays diffusing the air with different scents with the press of a button.

Moving across the National Mall to the the National Museum of Asian Art, there is an interactive exhibit also created with visually impaired museum visitors in mind. Funded by the Smithsonian Accessibility Innovation Fund the Interactive Cosmic Buddha is located in a secluded hallway of the museum where the exhibit’s video narrator can be properly heard.14 Visitors can take a seat or stand next to a three-dimensional replica of a sixth-century Chinese Buddha and the narrator will voice instructions on how to interact.

Figure 3

Figure 3It is notable that the narrator uses directional terms for those who are blind or have low vision, so that they can participate in the interactive exhibit as well. Particularly, the three metal plates’ locations are described for visitors who may have difficulty finding them. When touched, these plates trigger a narration of information about that specific part of the Buddha statue. Additionally, there is a bronze plate with braille at the base of the replica which the visitor is instructed to touch by the exhibit narrator so that the rest of the interaction begins. The exhibit also features three stone tablets with raised tactile illustrations depicting the three areas that have the metal plates. This is useful for visitors, especially those with little to no vision, to get a sense of the description as the narrator describes the Chinese Buddha.

Auditory Accessibility Technologies within the Smithsonian Institution

The Smithsonian Institution museums provide induction loop assistive listening systems through receivers for visitors to use. Induction loop assistive listening devices are used in tandem with hearing aids through a wireless, magnetic signal when the aids are set to the telecoil setting. For an induction loop assistive listening system to work there must be three components. The first is a microphone to pick up the sound or word, then an amplifier registers the signal which is sent through a loop cable that is built around a specific area.15 For example, in the National Museum of American History’s Molina Family Latino Gallery, induction loops are installed around the exhibition for patrons who are deaf or hard of hearing. Labels are shown on varying sections of the gallery to illustrate where induction loops are installed for use.

Figure 4

Figure 4Each of the Smithsonian Institution museums also provide assistive listening devices to those who benefit from them for certain exhibitions. Assistive listening devices use “direct sound amplification or visual or vibrotactile alerts” that help museumgoers who are deaf or have hearing loss communicate in a more effective manner.16 These devices are typically small hand-held amplifiers that will enhance sounds around a person and into their ear through a hearing loop. Assistive listening devices can be used in conjunction with telecoils, hearing aids without telecoils, or without any hearing aids.17

In addition to assistive listening technologies, the Smithsonian Institution exhibits include open captioning with each of their video presentations. Open captions are labeled as such when they are “permanently embedded in the audiovisual material.”18 Open captions are incredibly helpful for museum visitors who are hard of hearing because it can help them gain the information if there is a large crowd or if the museum exhibition contains loud or multitudes of noises. In the Molina Family Latino Gallery, the captions, on the exhibits and the digital screens, are available in both the English and Spanish language to include visitors who are fluent in either language. Captioning is incredibly helpful for people who are deaf or have hearing loss, but captions can also help hearing individuals as well. Museums often have events, field trips for children, or other noisy events that can limit one’s ability to hear, so open captioning can help with these situations. Open captioning is popular among many communities, so much so that users on social media, such as Twitter, are advocating for movie theatres and movie companies to begin implanting open captions in their films.19

Mobility Accessibility Technologies within the Smithsonian Institution

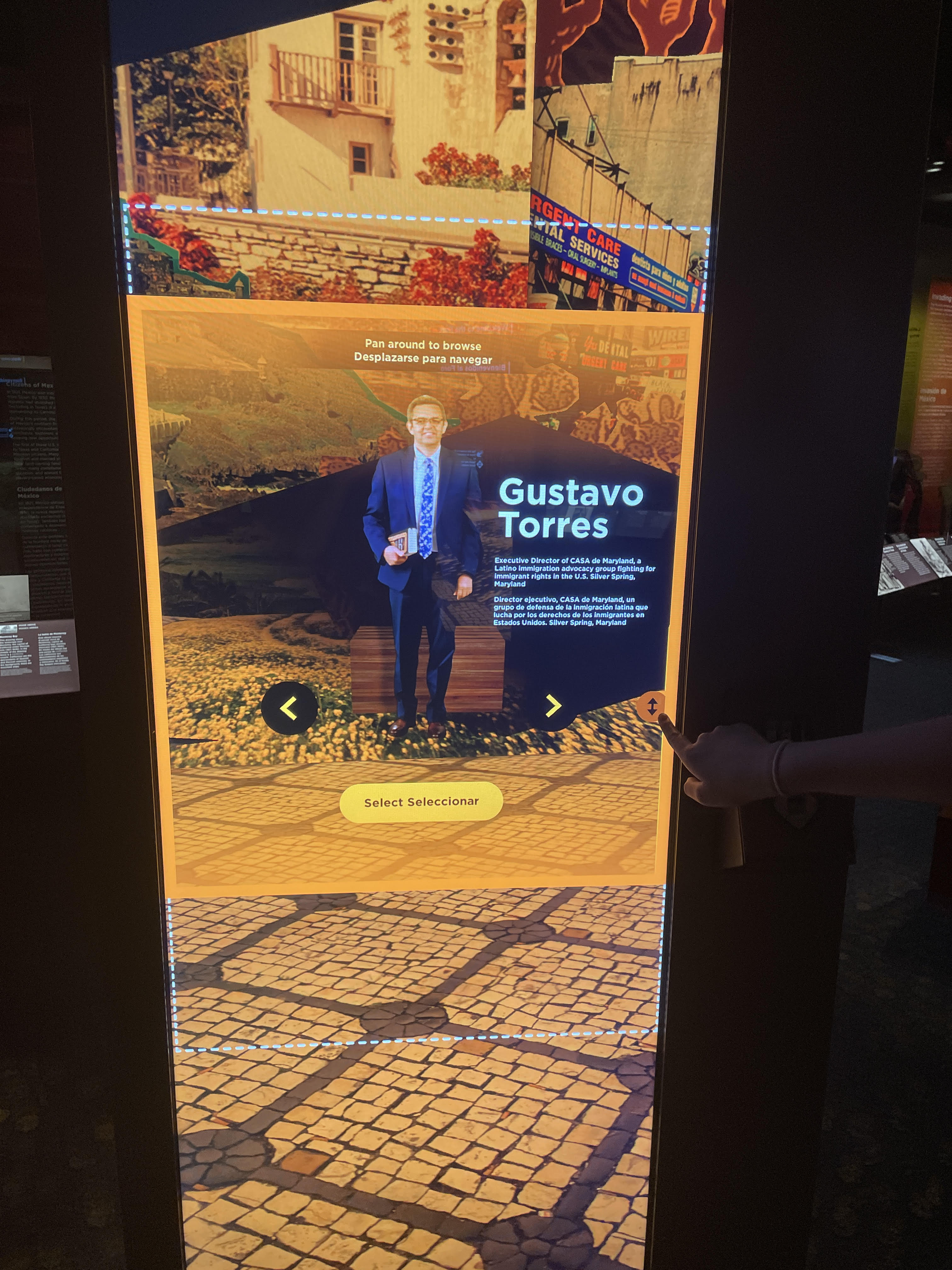

As previously mentioned, the Molina Family Latino Gallery does a fantastic job of accessible exhibition design. This stands true for museum visitors who have physical impairments such as mobility issues. Particularly, the Molina Gallery includes large vertical interactive screens that are able to be interacted with by patrons who have vision or hearing issues, but also those who may be in a wheelchair. These screens are enabled to have the presenter on screen be lowered or raised to any height so that they are on eye-level with the individual in front of the screen. This feature is a great start to digital technology being regularly incorporated into exhibits to extend interaction for museum visitors with mobility issues.

Figure 5

Figure 5Prior to the opening of the Molina Family Latino Gallery, the Smithsonian Institution created a virtual reality (VR) component to the Renwick Gallery’s No Spectators: The Art of Burning Man exhibit. This VR experience was a collaborative venture between the Smithsonian Institution, Intel, and Linden Lab, using the Linden Lab’s VR platform, Sansar.20 While the Burning Man exhibit itself is no longer available in person, the VR experience is still available online for people to continue to use for years to come. The team of contributors also wanted to create this experience so that individuals who were unable to visit the physical location could enjoy it.21 This avenue of digital technology is crucial to explore for many reasons, an important one being the opportunity for mobility impaired museum visitors to comfortably enjoy exhibits either from their home or in an area of the gallery for a more interactive feel with mobile VR headsets.

Digital technologies, such as VR headsets, have the potential to help the mental health of mobility impaired individuals. For example, studies into virtual reality have shown that patients experience less pain and anxiety after surgery when exposed to calm scenes via virtual reality.22 Many individuals who have less mobility and utilize wheelchairs could use VR and VR headsets to engage in moments of respite through VR tours through museums. It is vital for the Smithsonian Institution, and all museums, to strive for more virtual reality additions in their museums because it is a key method into accessibility for mobility impaired persons.

In the same regard, virtual tours can be incredibly useful for individuals who use wheelchairs. Many Smithsonian museums offer virtual tours on their own museum websites. The National Museum of Natural History has an extensive virtual tour website for both current and past exhibitions. Designed for both the computer and mobile phones, these tours are equipped to be used by visitors physically inside the museum and for exploring at home. Virtual tours like this can be utilized by museumgoers in wheelchairs for exhibits that were not made with disabilities in mind. Particularly, people can use these self-guided virtual tours on their phones when exploring museum exhibits that have artifacts and descriptions at varying levels and locations that cannot be properly read by visitors who use wheelchairs. Additionally, virtual tours have an opportunity to enrich the museum visit experience by providing more information and links to other websites where visitors can learn more about what they are viewing.23 This is an important quality of adding digital technology to museums because it serves the museum’s purpose and provides accessibility for all to learn from the institution.

Challenges with Museum Digital Technology Implementation

While I believe it is of extreme importance to prioritize digital technology implementation into as many museums as possible for accessibility needs, I understand that there are many challenges that need to be considered. It is estimated that there are approximately 35,000 museums in the United States and a majority of them are historical societies and general museums.24 As the largest museum complex in the world, the Smithsonian Institution is well-equipped to fund digital technology implementation in their exhibits through grants and donor funding. Unfortunately, many of these historical and general museums across the United States do not have the reputation and resources that the Smithsonian Institution does, so it is more difficult for them to include digital technologies into their budgets. In addition to this, financial recessions and global health pandemics can create loss of what little revenue streams these smaller institutions have.25 During these times, museum professionals have to work diligently to create fundraising efforts for their museums.

In addition to financial struggles surrounding the implementation of digital technology into museums, there are also issues of museums staying up to date with the new technological trend. How many times have visitors interacted with digital technology at a museum just for it to be outdated and broken? It is essential for museums to keep their technological efforts maintained. This can typically be mediated by hiring an individual or team of museum technology trained professionals for digital outreach, website design and content, as well as digital efforts within the physical museum. This is connected still to the issue of financial stability because these museum technology professionals are usually doing “invisible work,” which is subject to cutbacks and layoffs when financial crises emerge.26

Conclusion

Digital technology is a part of everyone’s day-to-day life and for those with accessibility needs, digital technology is a lifeline for communication and obtainment of information. As museums continue to work towards more diversity, equity, and inclusion in their spaces, it is crucial for institutions to include accessibility in those practices. By implementing digital technologies into accessible exhibit design, museums aren’t only welcoming individuals with disabilities to interact, but every museum visitor to interact personally with the exhibits. To the best of their ability, museums around the country, and the world, can use the Smithsonian Institution as a guide to work towards implementing digital technology for the physically impaired museum visitors in their community. Technology will undoubtedly continue to improve, and museums will grow alongside it to continue serving their communities.

Notes

-

Victoria State Government, “Teach with Digital Technologies,” Victoria State Government, last modified September 25, 2019, https://www.education.vic.gov.au/school/teachers/teachingresources/digital/Pages/teach.aspx#. ↩︎

-

Americans with Disabilities Act, “Maintaining Accessibility in Museums,” Americans with Disabilities Act, accessed November 3, 2022, https://archive.ada.gov/business/museum_access.htm. ↩︎

-

American Alliance of Museums, “Diversity, Equity, Accessibility, and Inclusion,” American Alliance of Museums, accessed October 11, 2022, https://www.aam-us.org/category/diversity-equity-inclusion-accessibility/. ↩︎

-

American Alliance of Museums, “American Alliance of Museums 2022-2025 Strategic Framework,” American Alliance of Museums, accessed October 11, 2022, https://www.aam-us.org/programs/about-aam/american-alliance-of-museums-strategic-plan/. ↩︎

-

Smithsonian Institution, “For Museum Professionals,” Smithsonian Institution, accessed October 11, 2022, https://access.si.edu/museum-professionals. ↩︎

-

Americans with Disabilities Act, “Introduction to the ADA,” Americans with Disabilities Act, accessed November 3, 2022, https://www.ada.gov/topics/intro-to-ada/. ↩︎

-

Americans with Disabilities Act, “2010 ADA Standards for Accessible Design,” Americans with Disabilities Act, accessed November 3, 2022, https://www.ada.gov/regs2010/2010ADAStandards/2010ADAstandards.htm. ↩︎

-

Americans with Disabilities Act, “Maintaining Accessibility in Museums.” ↩︎

-

Access Smithsonian, “Resources,” Access Smithsonian, accessed November 4, 2022, https://access.si.edu/resources. ↩︎

-

Kayla Randall, “The Smithsonian Debuts New Accessibility Technology for Blind and Low-Vision Patrons,” Washington City Paper, March 15th, 2019, https://washingtoncitypaper.com/article/181230/smithsonian-debuts-new-aira-accessibility-technology-for-blind-patrons/. ↩︎

-

Peggy McGlone, “Smithsonian’s Latino Gallery Makes Big Gains for Accessibility,” The Washington Post, June 14th, 2022, https://www.washingtonpost.com/arts-entertainment/2022/06/14/smithsonian-accessible-gallery-molina/. ↩︎

-

Elizabeth A. Courtney-Long et al., “Socioeconomic Factors at the Intersection of Race and Ethnicity Influencing Health Risks for People with Disabilities,” Journal of Racial and Ethnic Health Disparities 4, (2017): 213, https://doi.org/10.1007/s40615-016-0220-5. ↩︎

-

McGlone, “Smithsonian’s Latino Gallery.” ↩︎

-

National Museum of Asian Art, “Hands On with the Interactive Cosmic Buddha,” Smithsonian Institution, accessed November 5, 2022, https://asia.si.edu/interactive-cosmic-buddha/. ↩︎

-

Hearing Link Services, “Hearing Loops,” Hearing Link Services, accessed November 5, 2022, https://www.hearinglink.org/technology/hearing-loops/what-is-a-hearing-loop/ (sometimes%20called,T'%20(Telecoil)%20setting. ↩︎

-

Arizona State University Speech and Hearing Clinic, “What are Assistive Listening Devices,” Arizona State University, accessed November 5, 2022, https://asuspeechandhearingclinic.org/hearing/rehabilitation-services/assistive-listening-devices/what-are-assistive-listening-devices. ↩︎

-

Hearing Loss Association of America, “Assistive Listening Systems,” HLAA, accessed November 6, 2022, https://www.hearingloss.org/hearing-help/technology/hat/alds/. ↩︎

-

National Association of the Deaf, “What is Captioning,” National Association of the Deaf, accessed November 6, 2022, https://www.nad.org/resources/technology/captioning-for-access/what-is-captioning/. ↩︎

-

Carolyn Hinds (@CarrieCnh12), “It’s strange that people have to raise money for open caption devices that allow the hearing impaired to watch a movie that Disney marketed as being diverse, because…” Twitter, 7:12p.m., November 1, 2021, https://twitter.com/carriecnh12/status/1455311760525770754?s=46&t=R8kZm6yrcLId0hZSCyMrcw. ↩︎

-

Author’s note: Linden Lab sold Sansar in 2020. The collaboration with Intel and the Smithsonian Institution occurred while they still owned the platform. ↩︎

-

DJ Pangburn, “How the Smithsonian is Turning its Art Exhibitions into Virtual Reality Experiences,” Fast Company, August 4, 2018, https://www.fastcompany.com/90213035/how-the-smithsonian-is-turning-its-art-exhibitions-into-virtual-reality-experiences. ↩︎

-

Quina Baterna, “How to Make VR Gaming More Wheelchair-Accessible,” Make Use Of, August 26, 2021, https://www.makeuseof.com/how-to-make-vr-games-wheelchair-accessible/. ↩︎

-

Maria Chiara Ciaccheri, “Do Virtual Tours in Museums Meet the Real Needs of the Public? Observations and Tips from a Visitor Studies Perspective,” June 1, 2020, https://www.museumnext.com/article/do-virtual-tours-in-museums-meet-the-real-needs-of-the-public-observations-and-tips-from-a-visitor-studies-perspective/. ↩︎

-

Giuliana Bullard, “Government Doubles Official Estimate: There are 35,000 Active Museums in the U.S.,” Institute of Museum and Library Services, May 19, 2014, https://www.imls.gov/news/government-doubles-official-estimate-there-are-35000-active-museums-us. ↩︎

-

Paul F. Marty and Vivian Buchanan, “Exploring the Contributions and Challenges of Museum Technology Professionals During the COVID-19 Crisis,” Curator N.Y. 65, no. 1 (January 2022): sec. Museums and Museum Professionals in Times of Crisis, https://doi.org/10.1111/cura.12455. ↩︎

-

Marty and Buchanan, “Contributions and Challenges,” sec. Museums and Museum Professionals in Times of Crisis. ↩︎