II. Balancing Access and Ethics in Digitization

- Sophia Kaminski, The George Washington University

Digitization and its translation to an online format is often championed as an asset for museums as a means of providing expanded access to a wider audience. On average, approximately two to four percent of a museum’s collection will be displayed in galleries, an increase in digitization, however, can enable unprecedented access that otherwise would be unavailable. Additionally, an increase in digitized collections can facilitate a diversified experience for visitors and provide added levels of historical interpretation. Simply, digitization of cultural heritage is “fundamentally about democracy and human rights…Cultural heritage belongs to everyone and everyone should have the same opportunities to take part in and contribute to our cultural heritage.”1

Figure 1

Figure 1Furthermore, the process of digitization and online access also has the potential to reorient objects outside the western, colonialist perspective and agenda. To the benefit of source communities, digitization can allow for a subtle reclaiming of culture and is considered part of the restitution process. Additionally, digitization can work to build strong relationship with source communities and museums. Above all, it is also important to understand that digitization should not be considered a replacement to physical exhibitions. Instead of an inferior method of viewing objects and collections, digitization provides a parallel experience that allows for a unique perspective and interpretation.

In contrast to the praised effects, digitizing museum collections and making them available online also leads to important questions regarding whether vital context about the object is lost. For instance, while museums can largely control the environment in which objects are presented within their galleries, meaning they can provide context to orient visitors, the same is not always the case online. Online collections can be viewed outside of the museum’s anticipated context. As a result, this can lead to differing interpretations by internet users that while sometimes liberating for the object, can also be detrimental for the online collections and individuals depicted within them. The digitized collections may be used to promote harmful stereotypes that were entirely unanticipated prior to the museum’s efforts to increase digitization for greater online accessibility and transparency.

Although digitization and increased online access is generally lauded and viewed as progress for the development of museums and the cultural heritage institution, it must not be considered without its potential harm. While it is true that unprecedented access is a commendable achievement for museums, it can come at the cost of breaching privacy in regards to sensitive collections and a perpetuation of western ideals in the digitization process, augmenting an already prevalent power imbalance. In order for digitization to achieve its desired affects, an increase in access for a broader audience, strong ethics must be considered. Is it possible to achieve the balance of invaluable access while also abiding by ethical guidelines? This essay will use case studies from across the sector to unpack the issues of digitization related to privacy and the perpetuation of western/colonial power imbalances.

Museums acquire sensitive collections, those that contain vulnerable topics and individuals, for many reasons, one of them may be to address difficult histories in an ever-continuing pursuit of educating visitors. In fact, it may be argued that it is important for museums to obtain such collections. While on exhibition and in storage, museums can ensure, or strive to attempt, that sensitive collections, and people affected, are able to retain a sense of privacy and protection due to exhibition design or collaboration with source communities in regards to storage conditions. However, through digitization, the ability to ensure privacy can be hindered. “Memory Archive,” a collection of vulnerable testimonies and objects from the Holocaust within Swedish museums will serve as a case study for this ethical concern relating to digitization.

The “Memory Archive” was prepared as a part of a Swedish Government’s agency in 2003 titled, Living History Forum. This collection contains “over 100 video-taped testimonies from individuals with a connection to the Holocaust (e.g., victims, rescue workers, and bystanders).”2 Interestingly, this collection has been shielded from the public, defying a larger trend within museums to increase transparency of Holocaust collections. However, in 2019, Swedish Prime Minister Stefan Löfven declared the need for “a museum to preserve the memory of the Holocaust.”3 In addition, with the number of living survivors dwindling, pertinent considerations have arisen relating to increasing accessibility and transparency of this collection, evidently digitizing the Memory Archive. Stemming from the Prime Minister’s realization, it becomes important to question digitization and sharing collections in an online context. Ethical concerns abound when privacy concerns collide with a desire for increased access and must be considered, especially when objects can be radically recontextualized noted previously.4

A major concern with digitizing these testimonies is the need to protect privacy for individuals involved. Privacy is linked to anonymity, and while some argue that both should be preserved when necessary, opposing perspectives opine that situating anonymity in historical context as a priori efforts can neglect minority groups from important historical events.5 In connection to this opposing perspective, it is also important to recognize that often times collections of Holocaust materials are digitized in order to acknowledge individuality and to memorialize victims and survivors, seen through projects such as Shoah and Yad Vashem.6 Given the trend in eliminating privacy in Holocaust related collections, and its apparent acceptable nature, the ethical issue of privacy within digitization needs to be addressed. Is it appropriate to digitally produce these immensely vulnerable testimonies for a digital audience that can attract a host of negative and patently historically inaccurate comments and critiques? For those still living, has consent been addressed? These questions matter deeply in all museum collections, especially with topics as sensitive as genocide, something the Memory Archive has considered.

Zinaida Manžuch writes in, “Ethical Issues in Digitization of Cultural Heritage” to explicate the dangers related to breaching privacy for the benefit of greater accessibility. Privacy issues flourish through digitization and online access as copious amounts of personal information within cultural heritage documents and objects are brought to an online audience at an incredible rate. Intimate details of personal life-events are made visible for an overbearing audience. For objects and collections acquired before digitization prospects grew, the sensitive information referenced above would only reach visitors in the physical museum.7 Is it reasonable to assume that certain museum collections gathered prior to these efforts are not appropriate for digitization? Even in the case of information pertinent to Holocaust education? Returning to the case study of the Memory Archive within this debate, ethical concerns surrounding anonymity and privacy were strongly considered. Individuals in the collections who wished to collaborate with digitization efforts, creating important shared authority, were allowed to break their anonymity, facilitating a safe relationship between the source community and Museum.8 Bucking the trend of most Holocaust collections and museum digitization efforts, the Swedish Memory Archive is contemplating the sensitivity of oral testimonies that uncover humanities most vulnerable moments. Where legal requirements in the form of policies and laws are shaky, ethical considerations must remain dominant throughout digitization.

Tara Robertson wrote “Digitization: Just Because You Can, Doesn’t Mean You Should” to further expand upon the dynamics of digitization and online access breaching privacy concerns. In her writing, Robertson focused on the lack of sensitivity given to LGBTQ+ groups and Native Americans in digitization. Many universities engaged in flippant behavior while digitizing collections related to Native American as Robertson expressed, “I’ve heard similar concerns with lack of care by universities when digitizing traditional Indigenous knowledge without adequate consultation, policies or understanding of cultural protocols.”9 Moreover, Robertson acknowledged that “librarians need to take more care with ethical issues, that go far beyond simple copyright clearances, when digitizing and putting content online.”10 Efforts to digitize collections for the benefit of increasing accessibility must go beyond legal considerations. Underscoring Robertson’s pleas, it is imperative that ethical concerns are diligently considered and respected.

In stark contrast to what Robertson described, Mukurtu, “a digital collection platform that was built in collaboration with Indigenous groups to reflect and support cultural protocols” should serve as a guiding example for digitizing collections from minority communities by a majority group who often lack nuanced knowledge of these communities. Mukurtu represents as a stellar exemplar of ethical digitization.11

Aside from the above-mentioned need to consider balance for access and ethics, digitization’s benefits related to accessibility must also be weighed against an additional problem, the perpetuation of western ideas and colonialism. Firstly, it is important to note that as collections are digitized and made accessible to internet users, relevant information is transcribed from a Collections Management System (CMS) in order to create an object collection page that is displayed online. Unavoidably, a CMS holds inherent biases that work to uphold western knowledge systems and language, which starkly illustrates the present ethical dilemma.

According to Feminist and Queer digital humanity theories some CMS contain “encoded biases, false binaries, and implied hierarchies. Feminist thinking teaches us to question why such distinction have come about and what values they reflect- not just the categories, but the structure of the system itself.”12 Elaborating upon this blistering critique, a CMS is often hampered by rigidity. Ironically, a CMS informs our understanding and importance of an object, “if there is no way to hold a kind of knowledge or type of information in a collections management system, then it is relegated to a space outside of the official, institutional, source of knowledge about an object.” 13 Additionally, when CMS metadata is produced in order to contribute to part of a collection’s page, an internet user is unaware that “they are only seeing a part of the picture” and does not “acknowledge diverse ways of know” which are located outside the CMS metadata.14 This translates to the harmful realization that “collections management systems impose constrained notions of what is object information, and therefore, what is an object- and what is object knowledge.”15 Above all, the present dichotomy, an us vs them structure, encompasses the CMS along with the proliferation of specific knowledge systems that are the direct manifestation of western ideology and colonialism. It is this aspect that directly hampers the applauded benefits of digitization and increased access.

Digitization practices using a CMS as described above and colonialism within the cultural heritage institution are directly connected and as a result lead to great inequities and the misrepresentation of source communities. The Iziko South African Museum as well as the The Crying Child photograph housed within the Royal Danish Library will serve as case studies for this ethical issue. Additionally, through these case studies the inherent normalization of colonial knowledge and practices becomes widely apparent, especially on the digital front. As will be seen, the Iziko South African Museum depicts a strident effort to decolonize the digitization of material collections and the Royal Danish Library exposes unfortunate flaws while producing metadata for enslaved or colonized individuals.16

To begin, it is generally understood that within Danish and other colonial collections “images of enslaved and colonized peoples were predominantly envisioned by Europeans, who also controlled the means of production, rights of access, and dissemination.”17 The effects of such collecting practices reveal that source communities lack legal representation and perhaps more importantly, the visual representation of the individuals relayed to the public.18 As a result of this trend, “it has become clear that ethics of care requires a more nuanced and holistic organizational mindset to accommodate the vulnerabilities of postcolonial collections management.”19 To bolster the above point, a response to the Sarr-Savoy Report in 2018 noted the need to decolonize French institutions holding African material culture, strongly reinforcing the claim for ethics of care.20

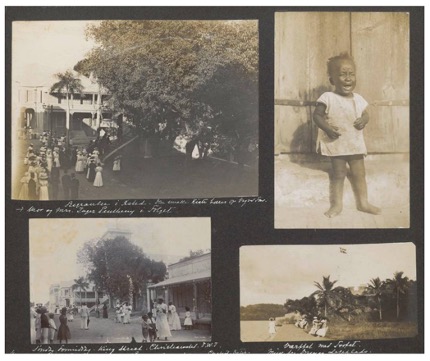

The photograph of the unidentified crying child held in the Royal Danish Library was taken in 1910 by Axel Ovesen a military officer who went to St. Croix as a young man in 1906, documenting tensions for enslaved individuals regarding their conditions after achieving emancipation in 1848. The child in the photograph is unnamed and as of now, unknown. To date, the photograph remains randomly pasted in private albums and donated to the Royal Danish Library.21

Figure 2

Figure 2It is important to note that digitization is certainly not a neutral process, rather, it is a process which reflects decisions made by the institution. Racialized terminology such as “slavery,” “racism,” and “Jim-crow”, etc. often remain the predominant terms within online object collections.22 Searching for images such as that of the crying child using racialized terms that perpetuate colonial ideals and systemic racism dematerialize and decontextualize historic objects and collections. Instead, images portraying extremely sensitive topics and vulnerable individuals lose all dimension and interpretation, certainly from the perspective of the source community. The harsh reality is that “photographic collections… ‘are reduced to, and managed as, data banks of images, understood to be uncomplicated, transparent and passive representations of truth.’”23 The results stemming from this process of digitization is extremely damaging and fails to honor the traumatic experiences of many minority groups. This represents another example of the reckless nature of digitization and increased online access in connection to western institutions remaining steadfastly rooted in colonialism, underscoring the need for a diligent adherence to ethics.

Perhaps what Gibson proposed in the case study surrounding the Iziko South African Museum provides an exemplary model for dismantling the power of colonialism within the sector in contrast to the treatment of the Crying Child photograph. In this example descendants of the Zulu community, the group represented in the collections that will be digitized, collaborated with the Museum and proposed alternative categories, classifications, and knowledge structures throughout the process in order to change how the museum represented their ancestors.24 As opposed to having predominantly white, western museums, “develop a definitive anticolonial narrative that might make a futile attempt to fill these archival gaps,” source communities such as those who self-identify as Zulu can “explore the possibility of producing alternative stories.”25

Through initiatives such as the previously mentioned Mukurtu and the Iziko South African Museum, western, colonial narratives will be challenged, eventually striking the “core museum activities of collecting, cataloguing, and classifying.” 26 Through efforts to include Indigenous narratives, these projects appear less as “add ons” or mere substitutes for colonial systems of knowledge, rather they can be regarded as equal or even prevailing in prominence for digitized objects/collections. It is important to note however, this must not constitute a substitute for repatriation, but “a broader decolonization process aimed at the restitution of knowledge.”27

Although digitization practices are fraught with colonial undertones as described above, many plausible arguments can be made which advocate for the continued process of making Indigenous and Native American objects/collections available online at an increased rate. To provide context, after the passing of NAGRPA (Native American Grave and Repatriation Act) in 1990, the term “digital repatriation” rose in prominence, described as “the return of cultural heritage items in some type of digital format to the communities from which they originated.” 28 Stemming from this monumental piece of legislation, digital repatriation has gained traction, allowing for renewed ownership by source communities.

What has resulted since 1990 is the Indigenous Digital Archive which aims to digitally return collections to source communities, providing a way of reversing colonialism and increasing a sense of cultural revitalization. This product is the result of collaboration between the Museum of Indian Arts and Culture, the Indian Pueblo Cultural Center, and the New Mexico State Library’s Tribal Libraries Program, among many other cooperating organizations. 29 Stated in an August 2018 Pasatiempo magazine, “it’s important to understand the Indigenous Digital Archive as more than a socially collaborative archive. It’s best seen as the tech component of a larger social movement that has pushed for Native American families to repair and recover from intergenerational trauma inflicted by Indian boarding schools.”30

Emerging from the creation of Indigenous Digital Archives, which promotes ethical accessibility of Indigenous collections, is the realignment of ownership and the path to mending generational trauma. Some of the multiple projects highlighting an Indigenous interpretation of online collections in the Archive are, American Indian Histories and Cultures, American Indians of the Pacific Northwest Collection, and the Duke Collection of American Indian Oral History.31 Therefore, as each project has the ability to reach beyond Indigenous communities to educate a wider audience on Native American culture and history, they also return power and a sense of ownership to source communities, an authority which had been previously demolished. In this instance, digitization of objects/collections from vulnerable groups is seen as extremely beneficial for source communities and wildly educational for others groups. To reiterate, ethical digitization is not only achievable but strongly encouraged.

It has been well established that increasingly open access to museum collections via online collections pages is also extremely beneficial to the institution. Noticeably, prominent museums such as the Metropolitan Museum of Art and the J. Paul Getty Museum have exponentially increased access to digitized collections. The Metropolitan Museum of Art’s (The Met) open access initiatives “’grew out of [their] 2006 strategic plan’ and was officially announced in 2007, making it one of the first major museums in the United States to adopt OA.” 32 As of October 2020, The Met’s online art collection provides digital access to more than 375,000 high resolution JPEG images of public domain works.33

Figure 3

Figure 3Similarly, The Getty’s Open Content Program, which debuted in August 2013 has made over 10,000 images of public domain works accessible to the public. As of 2020 the number has risen to over 74,000. The result of these efforts is that the various publics of the J. Paul Getty Museum have unprecedented access to the Museum’s robust collection.34

Figure 4

Figure 4Although art museums have notoriously “gatekept” collections from public exploitation, an earnest attempt to deconstruct this notion by the Association of Art Museum Directors (AAMD) has led to the gradual acceptance of providing unprecedented digital access to collections.35 Since the AAMD’s initiative dating back to 2005, a burgeoning number of museums have adapted their collections for a digital format, reaping benefits such as increased access to their institution by a diversified audience and an inevitable boost in publicity.

As stated previously, digitization and online access in museums and other cultural heritage institutions has proven to disrupt the sector’s ethics by exhibiting a lack of care to sensitive collections depicting vulnerable individuals and perpetuating western, colonial knowledge systems that are undeniably harmful. However, if executed successfully, ethical digitization is a process which can be instrumental for the advancement of museums, libraries, archives, etc. Previously mentioned examples such as Mukurtu and the Indigenous Digital Archives illustrate the notion that ethical digitization and online access is certainly achievable.

Finally, the undeniable ethical complications previously mentioned must be considered in this nuanced topic. In general, most museums are trying their best to achieve this task, however, multi-faceted problems must be dealt with in order to generate success. It is imperative that digitization efforts are firmly rooted in unwavering ethical actions. Without laws or regulations in place to prevent unethical behavior, it is important to acknowledge what is appropriate and what is damaging for vulnerable communities within a museum’s collection. If digitization works to deconstruct colonial undertones and respects the sensitive nature of collections, the incredible access granted to online visitors is invaluable. However, if racist terminology is perpetuated due to a lack of care, failing to honor victims and survivors of mass atrocities within museum collections, the results of unethical digitization are unsuccessful at best and irreversibly damaging at worst.

Notes

-

Malin Thor Tureby and Kristin Wagrell, “Digitization, Vulnerability, and Holocaust Collections. (Russian),” Santander Art & Culture Law Review, no. 2 (July 2020), https://doi.org/10.4467/2450050XSNR.20.012.13015, 88. ↩︎

-

Tureby and Wagrell, “Digitization, Vulnerability, and Holocaust Collections,” 92. ↩︎

-

Tureby and Wagrell, “Digitzation, Vulnerability, and Holocaust Collections,” 92. ↩︎

-

Tureby and Wagrell, “Digitization, Vulberability, and Holocaust Collections,” 92-93. ↩︎

-

Tureby and Wagrell, “Digitization, Vulnerability, and Holocaust Collections,” 96. ↩︎

-

Tureby and Wagrell, “Digitization, Vulnerability, and Holocaust Collections,” 98. ↩︎

-

Zinaida Manžuch, “Ethical Issues In Digitization Of Cultural Heritage,” 4 (2017), 7. ↩︎

-

Tureby and Wagrell, “Digitization, Vulnerability, and Holocaust Collections,” 113. ↩︎

-

Tara Robertson Consulting, “Digitization: Just Because You Can, Doesn’t Mean You Should,” March 21, 2016, https://tararobertson.ca/2016/oob/. ↩︎

-

Robertson, “Digitization.” ↩︎

-

Robertson, “Digitization.” ↩︎

-

ICOM CIDOC, “Making Space for Diverse Ways of Knowing in Museum Collections Information Systems - Erin Canning (August 2020),” https://cidoc.mini.icom.museum/blog/making-space-for-diverse-ways-of-knowing-in-museum-collections-information-systems-erin-canning-august-2020/. ↩︎

-

ICOM CIDOC, “Making Space.” ↩︎

-

ICOM CIDOC, “Making Space.” ↩︎

-

ICOM CIDOC, “Making Space.” ↩︎

-

Laura Kate Gibson, “Pots, Belts, and Medicine Containers: Challenging Colonial-Era Categories and Classifications in the Digital Age: Töpfe, Gürtel Und Medikamentenbehälter: Herausfordernde Kategorien Aus Der Kolonialzeit Und Klassifikationen Im Digitalen Zeitalter,” Journal of Cultural Management & Cultural Policy / Zeitschrift Für Kulturmanagement & Kulturpolitik, no. 2 (July 2020), https://doi.org/10.14361/zkmm-2020-0204, 1; Temi Odumosu, “The Crying Child: On Colonial Archives, Digitization, and Ethics of Care in the Cultural Commons,” Current Anthropology 61, no. S22 (October 2, 2020), https://doi.org/10.1086/710062, 289. ↩︎

-

Odumosu, “The Crying Child,” 295. ↩︎

-

Odumosu, “The Crying Child,” 295. ↩︎

-

Odumosu, “The Crying Child,” 295. ↩︎

-

Mathilde Pavis and Andrea Wallace, “Response to the 2018 Sarr-Savoy Report: Statement on Intellectual Property Rights and Open Access Relevant to the Digitization and Restitution of African Cultural Heritage and Associated Materials,” SSRN Scholarly Paper, Rochester, NY, March 25, 2019, https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3378200, 115. ↩︎

-

Odumosu, “The Crying Child,” 291. ↩︎

-

Odumosu, “The Crying Child,” 298. ↩︎

-

Odumosu, “The Crying Child,” 299. ↩︎

-

Gibson, “Pots, Belts, and Medicine Containers,” 1. ↩︎

-

Gibson, “Pots, Belts, and Medicine Containers,” 4. ↩︎

-

Gibson, “Pots, Belts, and Medicine Containers,”4. ↩︎

-

Gibson, “Pots, Belts, and Medicine Containers,”4. ↩︎

-

Nancy K. Herther, “Digitization Provides Access to Native American Archives.” Information Today 36, no. 1 (February 1, 2019), 18. ↩︎

-

Herther, “Digitization Provides Access,” 18. ↩︎

-

Herther, “Digitization Provides Access,” 18. ↩︎

-

Herther, “Digitization Provides Access,” 19. ↩︎

-

Rachel Hoster, “Art Museums and the Public Domain: A Movement Towards Open Access Collections.” Visual Resources Association Bulletin 47, no. 2 (Fall/Winter 2020), 2. ↩︎

-

Hoster, “Art Museums and the Public Domain,” 3. ↩︎

-

Hoster, “Art Museums and the Public Domain, 3-4. ↩︎

-

Hoster, “Art Museums and the Public Domain,” 1. ↩︎