VIII. Beyond Zoom: Digital Museum Education Today

- Sarah Farver, The George Washington University

As the world emerges from the Covid-19 pandemic, museums face new expectations when it comes to interacting with audiences online. During the height of museum closures, institutions turned primarily to teleconferencing technologies, such as Zoom, to deliver educational programs. However, the grace period of experimenting with virtual or hybrid museum education has passed. Now, digital museum audiences expect technological proficiency at the least and innovative features that suit hybrid lifestyles and combat Zoom fatigue at best. Amid financial strain and staff burnout, museums in the United States of all sizes require guidance for future success in digital museum education.

Scalable solutions for digital education programming at small, medium, and large museums in the wake of the Zoom boom will help museums emerge from the pandemic stronger and more in tune with their communities’ needs. Rooted in a rich history spanning decades before Covid-19, successful digital museum education must learn from its own past, following standards and best practices developed along the way. With a solid foundation in accessible, sustainable, and high-quality digital education practices, museums of all sizes and abilities can build adaptable, individualized programming portfolios as they navigate post-Covid society.

In implementing the following recommendations, museums are encouraged to self-identify as small, medium, or large based on pertinent factors. Guidance and case studies for each class of museum adhere to the following rough estimates: small museums have fewer than 20 full-time staff members, medium museums have 20-100 full-time staff members, and large museums have over 100 full-time staff members.

History of Virtual Museum Education

While the Covid-19 pandemic seemingly brought on a Cambrian explosion of virtual museum programming, most museums actually spent lockdown deploying distance learning techniques with decades of pedagogical precedent. In the early 1990s, museums first began using videoconferencing technology as a way of interacting with visitors remotely, primarily focusing on school groups.1 Despite this early availability, widespread adoption would wait until the early 2010s as relevant technology, from webcams to software applications, for both museums and schools grew more affordable. By the end of the early 2010s, museums also had access to a variety of digital education tools beyond videoconferencing to choose from, including discussion forums, wikis, podcasts, and more.2

As smaller and midsize museums began dipping their toes into the digital education pool, larger institutions continued pushing the limits through large-scale collaborations. On the east coast of the United States, the Metropolitan Museum of Art (Met) and American Museum of Natural History joined forces exploring methods of virtual learning for students that adapted to more STEM-centered curricula, later teaming up with west-coast developments from the California Academy of Sciences and Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco.3 These online museum learning projects, typically involving synchronous videoconferencing components as well as asynchronous online discussion forums, also developed as partnerships between museums and nonprofit organizations.4

Despite this flourishing of creative partnerships and experiments with novel technologies, museum digital education fell into a relatively stagnant period from the early 2010s through early 2020. With shifting priorities and low on-site visitor usage of mobile applications, cellphone-based audio tours, and QR codes, museums seemed less willing to invest in new digital education initiatives. By February of 2020, less than fifty percent of art museum directors viewed digital education as a priority.5 Ultimately, it took a natural disaster of epic proportions to shake museum digital education back into motion.

As American life shifted into physical isolation in March 2020, museums quickly turned to the available technological tools and strategies they previously underused or neglected. Social media campaigns encouraged engagement with #MuseumFromHome content while overworked school teachers turned to virtual field trips as opportunities for escapism rather than curricular enhancement.6 In some cases, the pandemic also returned museums to analog practices, such as the Met’s meals-on-wheels-style delivery of art kits to retirement communities with roots in the 1980s.7

The digital scramble in the early days of the pandemic also highlighted the inequality within the digital divide between traditional museum audiences who retained access to online resources and marginalized groups who struggled with the financial demands of the global crisis. Some museums stepped up by offering relevant diversity, equity, accessibility, and inclusion (DEAI) resources to their communities, but countless others fell short of moving beyond empty statements of solidarity.8

By 2021, museums and their audiences found themselves in fundamentally new relationships with each other and the digital technologies connecting them. Due to increased online interaction with museums, many museum visitors expressed Zoom fatigue. 9 In an increasingly hybrid – digital and in-person – world, museums stand to gain even greater audience reach than possible in pre-pandemic times, but the grace period for technical experimentation has ended. 10 Those interacting with museums online, whether through a livestreamed program, social media platform, or other digital resources, expect streamlined experiences that deliver high-quality content.

Standards and Best Practices

Moving forward into a world forever changed by the Covid-19 pandemic, museums must follow battle-tested standards and best practices for digital museum education for future synchronous and asynchronous learning experiences. Adhering to the following tenets of accessibility, quality, and sustainability will help museums of all sizes and abilities provide sound virtual education offerings.

Just as museums champion accessibility in their on-site experiences, they must foster equally accessible environments for online audiences that go beyond legally required minimums. Museum accessibility best practices extend beyond regulations addressing physical access needs into financial access. According to the International Council of Museums’ recently adopted definition, museums are “open to the public, accessible and inclusive…offering varied experiences for education, enjoyment, reflection and knowledge sharing."11 Naturally, this mandate applies to the whole of museum experience, including digital museum practices.

Beginning with the core infrastructure of museums’ online presence, museum websites, social media channels, and resources available through each must adhere to Web Content Accessibility Guidelines (WCAG). Meeting WCAG requirements includes implementing text hierarchies, alternative text captions for non-textual elements, and captioning for video content.12 Museums should comply with these standards in all digital education applications, from synchronous videoconferencing or livestreaming sessions to asynchronous activities delivered through downloadable documents such as PDFs. Meeting these standards keep museums in step with accessibility requirements, but also increase the discoverability of their materials online, helping them reach larger audiences.

While these standards apply to physical digital accessibility, such as screen-reader compatibility for users with low vision, keeping resources free or affordable within reason help museums address needs of financial accessibility. With the economic fallout of the Covid-19 pandemic, schools facing funding cuts continue eliminating arts or humanities resources not deemed as “priorities."13 In response, museums should seek grant funding or other philanthropic resources that keep virtual school learning experiences free or low cost, particularly to vulnerable institutions such as Title I schools.14 Since the pandemic also revealed the gap in technology access for those of limited financial means, museums should also consider creative methods of reaching these audiences to provide them with digital educational materials.15 Museums can create opportunities for accessibility by partnering with schools, libraries, and other institutions capable of connecting the public with Internet access and web-accessible devices so that their virtual programming extends beyond typical museum audiences. Benefitting more than just their audiences, museums offering accessible, dependable educational resources increase public trust in their institutions, sustaining them financially as well as ethically.

Maintaining public trust in museums as reputable sources of information hinges on providing high-quality content in online educational resources reflective of high quality in-person experiences. In accordance with the standards of the American Alliance of Museums, museums must account for “the characteristics and needs of its existing and potential audiences” and must “[assess] the effectiveness of its interpretive activities and [use] those results to plan and improve its activities.”16 Thus, museums should practice community engagement as a means of providing high-quality digital education materials that serve their intended audiences. Despite continued claims of progressiveness, museums often struggle to break out of the long-held, colonialist mold of a teacher-student relationship when addressing their communities.17 True community engagement constitutes a reciprocal relationship built over time between a museum and a given population, resulting in projects – in this case educational programs – that value multiple ways of knowing. Conveniently, this model reflects the constructivist education approach that equalizes educator and learner used in effective digital museum pedagogy.18 Conversations with community stakeholders should thus guide digital museum education development, from platforms used to deliver content to the formats of content present and even the scope of the content itself. Museums should also undertake evaluations throughout the various phases of development as a way of ensuring that community needs are met.

However, museums can only create high-quality digital education programming by following best practices in museum sustainability. In this context, sustainability refers to adequate staffing and resources supporting the livelihood and longevity of virtual museum education projects. The graveyard of virtual museum resources still present, but not updated since the early days of the pandemic, lingering on museum websites suggest a deficit in staff resources directed towards sustained digital content. Some museum staffs can find aid through their community engagement practices, with collaborative efforts sharing the burdens of content creation and maintenance.19 Yet, such collaborations in and of themselves require museum staff time for building and facilitating these relationships. In the interest of budgeting staff time, museums must narrow the scope of their projects to the most feasible and impactful by first determining a community’s needs and then determining how their museum is uniquely positioned to meet those needs.

Small Museum Recommendations

As small museums navigate the burdens of post-pandemic digital education, they should remain open-minded with their digital offerings to participate in knowledge sharing through like institutions and stretch programming already in place. Though typically focused on local audiences, small museums can use digital education strategies to reach the large percentages of museum goers continuing to engage with museums virtually.20 Thankfully, effective digital education remains rooted in the constructivist education principles that museum educators have implemented through in-person programming for decades. At its core, constructivist education empowers learners to develop their own meaning out of an experience, supporting a more equalized environment where educators and learners share authority.21 Teleconferencing applications like Zoom tend to promote hierarchical structure, favoring a single voice rather than allowing multiple conversations simultaneously. Therefore, museums in the post-Covid era should carefully consider the digital applications that they use to promote constructivist education approaches. For small museums, this does not necessarily require high-cost investments. As noted by museum educator Susan Bernstein, it is more important for museums to use the technology that they have in “new and interesting ways” than it is for them to simply use new technology.22 To this end, museums can use their existing websites as a starting point for offering digital education resources and modify their in-person programming to adapt to hybrid audience needs.

President Lincoln’s Cottage serves as an excellent example of a small museum providing digital offerings suited to hybrid audiences within the scope of its resources and mission. One simple yet effective element of their webpage for “Educator Resources” provides links to the websites of similar organizations, such as the Abraham Lincoln Historical Digitization Project, Ford’s Theater, and the Lincoln Home in Springfield. 23 Without added costs beyond the Cottage’s resources allocated to running their website, the museum provides learners with free choice to explore additional, relevant digital education opportunities. In the future, the museum could consider moving these virtual resources to a more publicly accessible webpage, such as the “Learn” page, to show that these resources are available for all learners, not just educators.

On a more advanced level, the Cottage also produces a podcast responding to questions posed by museum visitors.24 Although initiated before the pandemic, this digital resource kept the Cottage virtually accessible to learners throughout the museum’s temporary closure and continues resonating with listeners unable to visit the museum in person. At roughly 30 minutes in length, each episode seems approachable and can easily be downloaded and consumed as the listener goes about other tasks. While the Cottage’s podcast operates as an independent project, other museums could easily adapt the podcast medium as a means of recording live, in-person programming – a practice already implemented by some large museums.25 With the increased popularity of podcasts, recording and production materials have grown more affordable and user-friendly. Starting by adapting in-person programming into podcasts helps alleviate some time and content creation burdens, while their digital accessibility can help small museums diversify their virtual offerings beyond visually based resources.

Medium Museum Recommendations

For medium or midsize museums, effective digital museum education reaches beyond the now-standard virtual museum tour into more individualized, gamified experiences through the museum’s website. During the height of the Covid-19 pandemic, museums raced to produce online experiences simulating the in-person museum experience via Matterport, Google Arts and Culture, and other software and hosting sites. Unfortunately, these experiences often failed to live up to their educational goals as users struggled with navigation issues and distracting digital infrastructure. 26 In some cases, museums offering virtual tours in video format, such as The George Washington University Museum and The Textile Museum, found success with more digital views of the exhibition than in-person visitors.27 However, these videos lack interactive features that transform passive virtual experiences into participatory ones, a necessary shift to create lasting educational value.

Thus, midsize museums should reevaluate and gamify their virtual tours as a step towards producing more meaningful digital education content. Museums with more limited staff time and resources can begin by updating their video tours to include links to specific objects on the museums’ collections websites as they are referenced throughout the tour. This way, interested viewers can pause their passive experience for a more self-driven look into any given work that captures their attention, returning to the rest of the video if or when they feel satisfied. Working up the gamification ladder, museums can place their collections in the creative control of their audiences with programs akin to Minecraft Your Museum from National Museum Wales.28 Such online activities allow independent viewer-led exploration of objects in a museum’s collection or given exhibition, granting the user control over their own meaning making. This style of online museum education experience plays into the constructivist education approach that many museums strive for in their on-site experiences.29

With gamification presenting itself as a powerful method of creating successful, constructivist learning online, medium-sized museums in the post-pandemic era should not limit themselves to only gamifying their virtual tours. Since learning through play promotes positive motivation for learning in both formal and informal settings, museums should strive for more gamified digital learning materials that reach adult, family, and student audiences. 30 Creating these materials meets a real and present demand, as interactive online materials such as games and quizzes remain highly requested from schoolteachers in 2022. 31 These often asynchronous virtual education materials can also offer museum education teams some respite from facilitated experiences via Zoom or other teleconferencing applications.

Large Museum Recommendations

As museums push their virtual education resources into the post-pandemic future, large museums can push the envelope towards fostering more inclusive communities through online educational offerings. With greater staff power and financial resources comes great responsibility, and large museums often shoulder this responsibility by serving as role models for the rest of the field. As evidenced by the American Alliance of Museum’s recent announcement on including diversity, equity, accessibility, and inclusion (DEAI) standards in the museum accreditation process, museums in the post-pandemic era must reach beyond current DEAI efforts.32 In terms of accessibility, large museums in particular should demonstrate that digital education initiatives serve communities with specific access needs, expanding upon the digital accessibility standards previously outlined in this paper. Striving for inclusivity that fosters real community proves an even greater challenge for large museums catering to broad audiences but represents a crucial shift in museums becoming more transparent and approachable in our hybrid world.

When considering the future of accessible digital education resources in large museums, the Metropolitan Museum of Art (Met) springs to mind. One of the largest and best-endowed museums in the United States, the Met’s long history of serving learners with disabilities now includes dedicated virtual programming for visitors with developmental and learning disabilities, visitors with dementia, and visitors who are blind or partially sighted, respectively.33 Each of these virtual programs recreates an in-person program that existed prior to the pandemic via teleconferencing technology. While several of these synchronous virtual programs provide interactive elements via activity kits mailed to participants that allow for individualized meaning-making, the level of social interaction is difficult to gauge. 34 On the other hand, the Met’s synchronous virtual programming for visitors with dementia seems entirely socially focused, helping build community, yet lacking a physically interactive element for full constructivist learning. As a large museum, the Met should diversify its accessibility programming to fill the respective gaps of relationship building and physical meaning-making for more enriching digital education in the post-pandemic future.

Meanwhile, the Met’s asynchronous, digitally accessible learning tools provide a launch point towards greater community building and inclusion. The museum runs a dedicated Facebook page, “Access at The Metropolitan Museum of Art,” which serves as a virtual bulletin board announcing accessible museum programming from the Met and fellow museums as well as resources ranging from film screenings to online courses curated for their disabled community. 35 This communal sharing that extends beyond promotion of Met-sponsored events reveals a conscientious effort for inclusion, yet the page remains limited in its current state. Today, many museums and adjacent institutions explicitly use social media channels as tools for education rather than promotional marketing.36 By operating as a Facebook page as opposed to a Facebook group, the Met serves as a broadcaster rather than a facilitator. Changing this approach could see Facebook used more directly as an educational tool with the equalized educator-to-learner relationship necessary for true constructivist education.

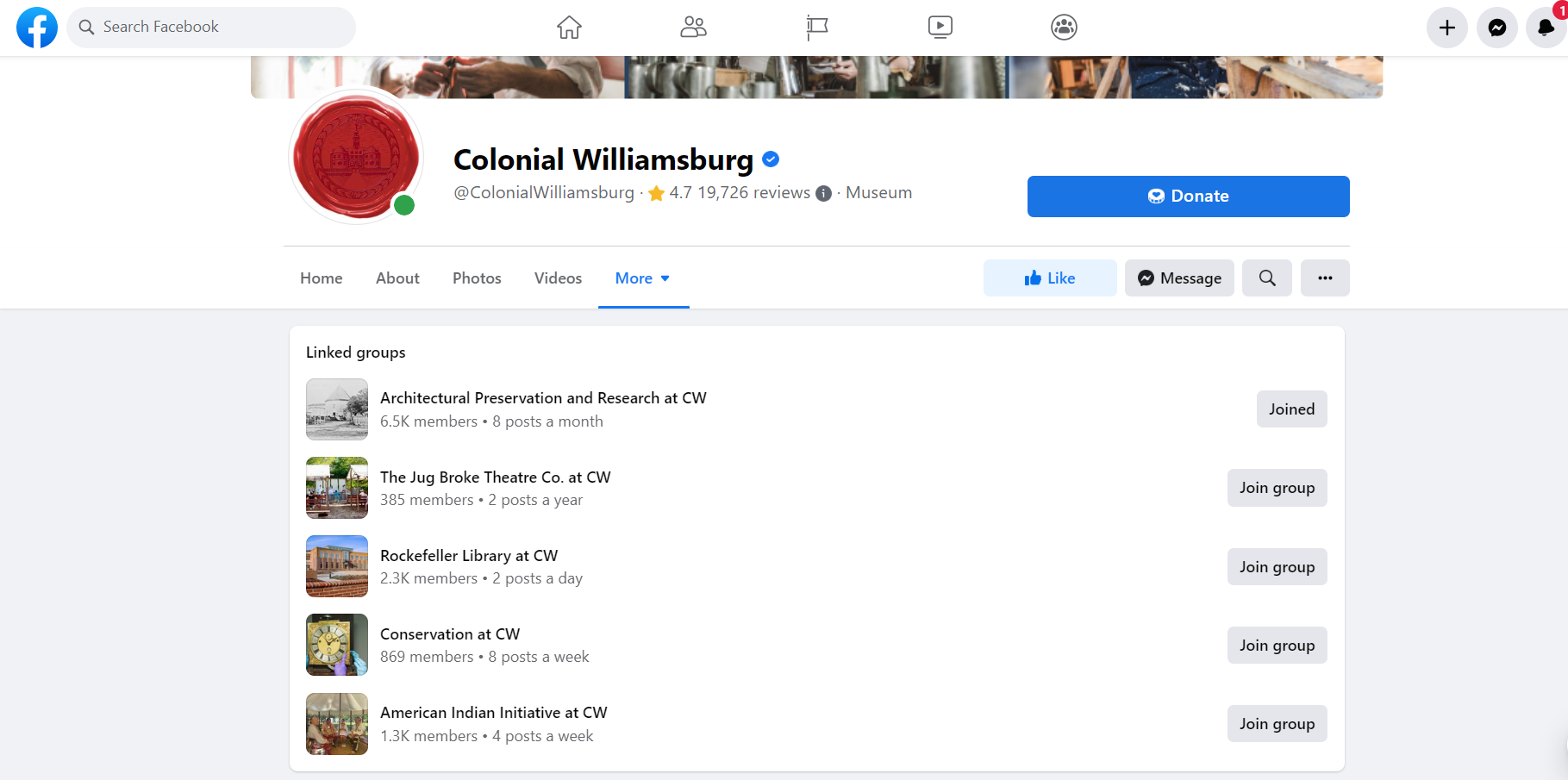

Moving towards a more inclusive model, the Met can look to fellow large museums’ endeavors in education-driven, community-focused Facebook groups, such as those run by Colonial Williamsburg. Easily located on the museum’s Facebook page, Colonial Williamsburg currently maintains five museum-sponsored Facebook groups, including two private groups created in 2022. 37 Allowing conversation between niche groups within a larger institution creates a more intimate atmosphere for informal digital education, which many large museums often struggle to produce. Creating space for knowledge sharing among affinity groups can happen on a number of platforms, so while Facebook can serve as a launchpad, large museums should look towards working with ethical platforms that support their missions and values. As large museums strive towards inclusion in our increasingly digitally attuned world, they must continue pushing staff resources towards community-based constructivist learning.

Conclusion

For museums of all sizes, successful navigation of post-Covid society requires effective digital education practices that build on recent history and respect visitor expectations of high-quality digital experiences. These practices must extend beyond teleconferencing platforms to form meaningful and inclusive educational interactions that bolster museums’ unique positions as trusted public institutions. By adapting current digital offerings and programming through the recommendations supplied here, museums can gradually scale up their digital education resources while avoiding the risks associated with novel experimentation. Staying true to their missions and areas of expertise, museums participating in digital museum education beyond Zoom can expand knowledge sharing and meaning making with new media, new approaches, and new ideas.

Notes

-

William B. Crow and Herminia Din. Unbound By Place or Time: Museums and Online Learning (Washington, DC: The AAM Press, 2009), 6. ↩︎

-

Crow and Din, 33-34. ↩︎

-

William B. Crow and Herminia Din, All Together Now: Museums and Online Collaborative Learning (Washington, DC: The AAM Press, 2011), 11 & 49. ↩︎

-

Crow and Din, 88. ↩︎

-

Jamie Wallace et al., “Pivoting in a Pandemic: Supporting STEM Teachers’ Learning Through Online Professional Learning during the Museum Closure,” Journal of STEM Outreach 4, no. 3 (2021): 2, DOI: https://doi.org/10.15695/jstem/v4i3.11. ↩︎

-

Wallace et al., 6. ↩︎

-

Tim Deakin, “How The Metropolitan Museum of Art Used Conversation to Reduce Social Isolation,” Museum Next, August 31, 2022, https://www.museumnext.com/article/art-conversation-to-reduce-social-isolation/. ↩︎

-

Audrey Hudson, “Virtual School Programs at Art Gallery of Ontario,” Museum Next, September 16, 2022, https://www.museumnext.com/article/virtual-school-programs/. ↩︎

-

Wilkening Consulting, “Virtual Audiences, Part 2: Who It Worked For…And Why It Didn’t Work For Everyone,” Wilkening Consulting, October 19, 2021, https://www.wilkeningconsulting.com/uploads/8/6/3/2/86329422/2021_virtual_content_part_2.pdf. ↩︎

-

Colleen Dilenschneider, “Increased Digital Engagement Is a ‘New Normal’ for Cultural Entities (DATA),” Know Your Own Bone, September 29, 2021, https://www.colleendilen.com/2021/09/29/increased-digital-engagement-is-the-new-normal-for-cultural-entities-data/. ↩︎

-

International Council of Museums, “Museum Definition,” International Council of Museums, last modified August 24, 2022, https://icom.museum/en/resources/standards-guidelines/museum-definition/. ↩︎

-

Web Content Accessibility Guidelines are determined by the World Wide Web Consortium, an international group run by the Massachusetts Institute of Technology alongside other affiliates. “How to Meet WCAG Quick Reference,” Web Accessibility Initiative, last modified October 4, 2019, https://www.w3.org/WAI/WCAG21/quickref/. ↩︎

-

Rebecca Hardy Wombell, “Lockdown learning – the digital education resources that raised the game,” Museum Next, June 17, 2021, https://www.museumnext.com/article/lockdown-learning-the-digital-education-resources-that-raised-the-game/. ↩︎

-

In the United States, Title I schools are schools in which children from low-income families make up at least 40 percent of enrollment. Improving Basic Programs Operated by Local Educational Agencies (Title I, Part A), U.S. Department of Education, last modified October 24, 2018, https://www2.ed.gov/programs/titleiparta/index.html. ↩︎

-

Jayatri Das and Mikey Maley, “The Brain Science of Museum Learning,” in Museum Education For Today’s Audiences: Meeting Expectations With New Models, ed. Jason L. Porter and Mary Kay Cunningham (Lanham, Maryland: Rowman & Littlefield, 2022), 222. ↩︎

-

“Education and Interpretation Standards,” American Alliance of Museums, accessed October 12, 2022, https://www.aam-us.org/programs/ethics-standards-and-professional-practices/education-and-interpretation-standards/. ↩︎

-

Bernadette Lynch, “The Gate in the Wall: Beyond Happiness-making in Museums,” in Engaging Heritage, Engaging Communities, ed. Bryony Onciul (Woodbridge: Boydell & Brewer, Incorporated, 2017), 24. ↩︎

-

Megan Ennes et al., “Museum-Based Online Learning One Year After Covid-19 Museum Closures,” Journal of Museum Education 46, no. 4 (2021): 477, DOI: 10.1080/10598650.2021.1982221. ↩︎

-

Paul Born, “Community Collaboration: A New Conversation,” The Journal of Museum Education 31, no. 1 (2006): 11, http://www.jstor.org/stable/40283902. ↩︎

-

Wilkening Consulting, “Virtual Audiences, Part 1: A 2021 Annual Survey of Museum-Goers Data Story,” Wilkening Consulting, October 12, 2021, https://www.wilkeningconsulting.com/uploads/8/6/3/2/86329422/2021_virtual_content_part_1.pdf. ↩︎

-

George Hein, “Evaluating Teaching and Learning in Museums,” in Museum, Media, Message, ed. Eilean Hooper-Greenhill (London: Routledge, 1995), 191. ↩︎

-

Susan Bernstein, “Looking Towards the Future,” in Presence of Mind: Museums and the Spirit of Learning, ed. Bonnie Pitman, (Washington, DC: American Association of Museums, 1999), 117. ↩︎

-

Educator Resources, President Lincoln’s Cottage, accessed November 8, 2022, https://www.lincolncottage.org/learn/educator-resources/. ↩︎

-

Podcast, President Lincoln’s Cottage, accessed November 8, 2022, https://www.lincolncottage.org/learn/podcast/. ↩︎

-

About, 100 Climate Conversations, accessed November 8, 2022, https://100climateconversations.com/about/. ↩︎

-

Jovana Milutinović and Kristinka Selaković, “Pedagogical Potential of Online Museum Learning Resources,” Journal of Elementary Education 15, Special Issue, (August 2022): 135, https://doi.org/10.18690/rei.15.Spec.Iss.131-145.2022. ↩︎

-

The George Washington University Museum and The Textile Museum, Unpublished internal document, 2022. ↩︎

-

Minecraft your Museum!, Amgueddfa Cymru, accessed October 23, 2022, https://museum.wales/learning/activity/405/Minecraft-your-Museum/. ↩︎

-

Hein, 190. ↩︎

-

Milutinović and Selaković, 135. ↩︎

-

Centrum Cyfrowe, “Open GLAM & education. Teacher’s and educator’s perspective on digital resources,” Centrum Cyfrowe, accessed October 23, 2022, https://centrumcyfrowe.pl/en/open-glam-2022/. ↩︎

-

American Alliance of Museums, “Diversity, Equity To Become Required for Museum Accreditation, Standards,” American Alliance of Museums, October 17, 2022, https://www.aam-us.org/2022/10/17/diversity-equity-to-become-required-for-museum-accreditation-standards/. ↩︎

-

Accessibility at The Met, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, accessed October 23, 2022, https://www.metmuseum.org/learn/accessibility. ↩︎

-

Virtual Discoveries (All Ages)—Majestic Making, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, accessed October 23, 2022, https://www.metmuseum.org/events/programs/met-creates/visitors-disabilities/discoveries/tudors-2022. ↩︎

-

Access at The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Facebook, accessed October 23, 2022, https://www.facebook.com/MetAccess. ↩︎

-

Bodleian Libraries, Twitter post, November 3, 2022, 1:12 p.m., https://twitter.com/bodleianlibs/status/1588217578736025605?s=20&t=Hz4yrz-TfuFVdvMhVMxsBw. ↩︎

-

Colonial Williamsburg, Facebook, accessed October 23, 2022, https://www.facebook.com/ColonialWilliamsburg/groups. ↩︎