XIV. Museums, Virtual Reality, and Historical Context

- Joseph Ingrum, The George Washington University

Museums are always looking for ways to integrate new engaging experiences into their galleries, often utilizing the latest technological innovations to entice visitors to learn more about the past. One emerging technology that may revolutionize how museums educate and present information is virtual reality. Virtual reality, or VR, is defined as “the use of computer modeling and simulation that enables a person to interact with an artificial three-dimensional (3-D) visual or other sensory environment” to “immerse the user in a computer-generated environment that simulates reality through the use of interactive devices.”1 These interactive devices most often include headsets with gloves or controllers. Examples of what we would consider VR have existed since the 1960s, with Ivan Sutherland creating the first VR head mounted display called the Sword of Damocles.2

By the 1990s, VR had reached a high point in popularity with the help of movies such as Lawnmower Man and the release of the first consumer VR headsets by video game companies Sega and Nintendo.3 However, the high cost and graphical limitations of this technology demonstrated the impracticality of these early attempts at virtual reality. Computer images at the time had to “omit textures, color and lighting subtleties,” creating images that were “so minimal that the end product [was] detrimentally reductivist.”4 As a result, virtual reality lost popularity by the start of the new millennium, once again becoming more science fiction than fact. When the company Oculus released their first consumer headset in 2012, VR became seen as a real possibility for public consumption. After the release of Oculus, the 2010s witnessed an explosion of new releases of VR headsets, including the HTC Vive, Playstation VR, and Samsung Gear VR.

As VR became more accessible throughout the 2010s, museums saw the opportunity to incorporate this technology into their galleries and education programs. Large institutions such as the Met, the British Museum, the Louvre, and the Tate Modern have all utilized VR to provide new experiences and educational opportunities to visitors. This paper will examine the various methods of how museums have utilized VR in their galleries and education programs in the years since the technology’s resurgence. Particular attention will be placed on VR’s ability to virtually recreate historic spaces, while also exploring how the technological advancements of VR help alleviate some of the common criticisms found with historical reconstructions, such as period rooms and living history museums.

One thing to note is that this paper will focus exclusively on VR and not augmented reality (AR) or mixed reality (MR) technologies. AR and MR involve placing “computer-rendered objects in the real world via a screen (or glasses or visor), and that object’s three-dimensional coordinates are supposed to be precisely calibrated within the real world.”5 An example of this would be The Met Unframed, an AR experience that allowed users to explore the Met’s collection from their smartphones during its Covid-19 closure. Along with touring galleries and playing mini-games, the app allowed you to “’borrow’ the artwork” and “place an image of a Met treasure into your own surroundings” through your smartphone screen.6 Both AR and MR technologies are valuable tools to help museums present information and interactive replicas of museum objects to those unable to visit the museum. AR is utilized more as a tool to bring virtual museum objects into the visitor’s real world, rather than transporting the visitor into a virtual world for that object. As a result, this paper will not explore AR and MR museum applications.

Gallery Recreations

One of the main types of VR experiences that dominate the museum field involves recreating a museum’s existing galleries in virtual space, either with images of the galleries or full 3D reconstructions in a virtual space. Most of these experiences are extensions of already existing online “virtual tours” that make museum galleries accessible to those unable to visit the museum. While most virtual tours are intended to be viewed through a computer screen, some do offer VR support for those wanting to use their headset to get a closer look at the galleries.

An example of this can be found at The British Museum with their VR experience British Museum React VR. For this project, in partnership with Oculus, the British Museum took 136 high-resolution 360° panorama photos of its Egyptian galleries and combined them to allow visitors to travel through the galleries.7 Included with this experience are “audio commentary from curators, text descriptions, and interactive 3D models of highlighted objects.”8 At the Australian Museum, the virtual tour of their First Nations exhibit Unsettled gives the option to view the galleries in an Oculus headset (Figure 1).9 Adding to the immersive quality of this tour is the audio and multimedia content playing in real time as you move through the galleries. Including audio and moving visuals significantly adds more life and immersion to the tour, removing the silence and static nature seen in most virtual tours.

Figure 1

Figure 1Rather than taking 360° photos of their galleries, some museums build new gallery spaces in VR to virtually display objects from their collection. Examples of these virtual galleries can be found at “VR-All-Art,” a company that specializes in building virtual exhibitions for art galleries, collectors, and museums. Instead of photographing existing galleries, VR-All-Art builds virtual recreations of galleries from the ground up. While most of these galleries are original designs by the company, others are cloned copies of existing real-world galleries. For example, VR-All-Art collaborated with the National Museum of Serbia to virtually recreate one of its galleries.10 The exhibit space has already been used for two different exhibitions, demonstrating the benefits of utilizing these virtual reconstructions. Unlike the 360° photos of galleries, virtually reconstructing the gallery in this way allows the museum to reuse this template for any new exhibition. The objects and labels can be easily switched out for each exhibit, granting the museum more flexibility with how it uses the space.

Linear Experiences

Museums are also utilizing VR to create what can be described as “linear experiences.” Rather than providing visitors a virtual space to move around in, these VR experiences play out as 360º films for the visitor to sit back and watch. The visuals for these experiences are often not grounded in reality and fully utilize the artistic capabilities of VR to transport visitors to other worlds. In 2021, the V&A Museum opened Alice: Curiouser and Curiouser, an exhibition that chronicles the history and influence of Lewis Carroll’s classic Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland. As part of this exhibit, the V&A created a VR experience called Curious Alice, where visitors are surrounded by “beautifully surreal Victorian-esque illustrations” of scenes and characters from the story.11 Visitors become immersed in Wonderland as they sit back and watch scenes from the popular story play out around them.

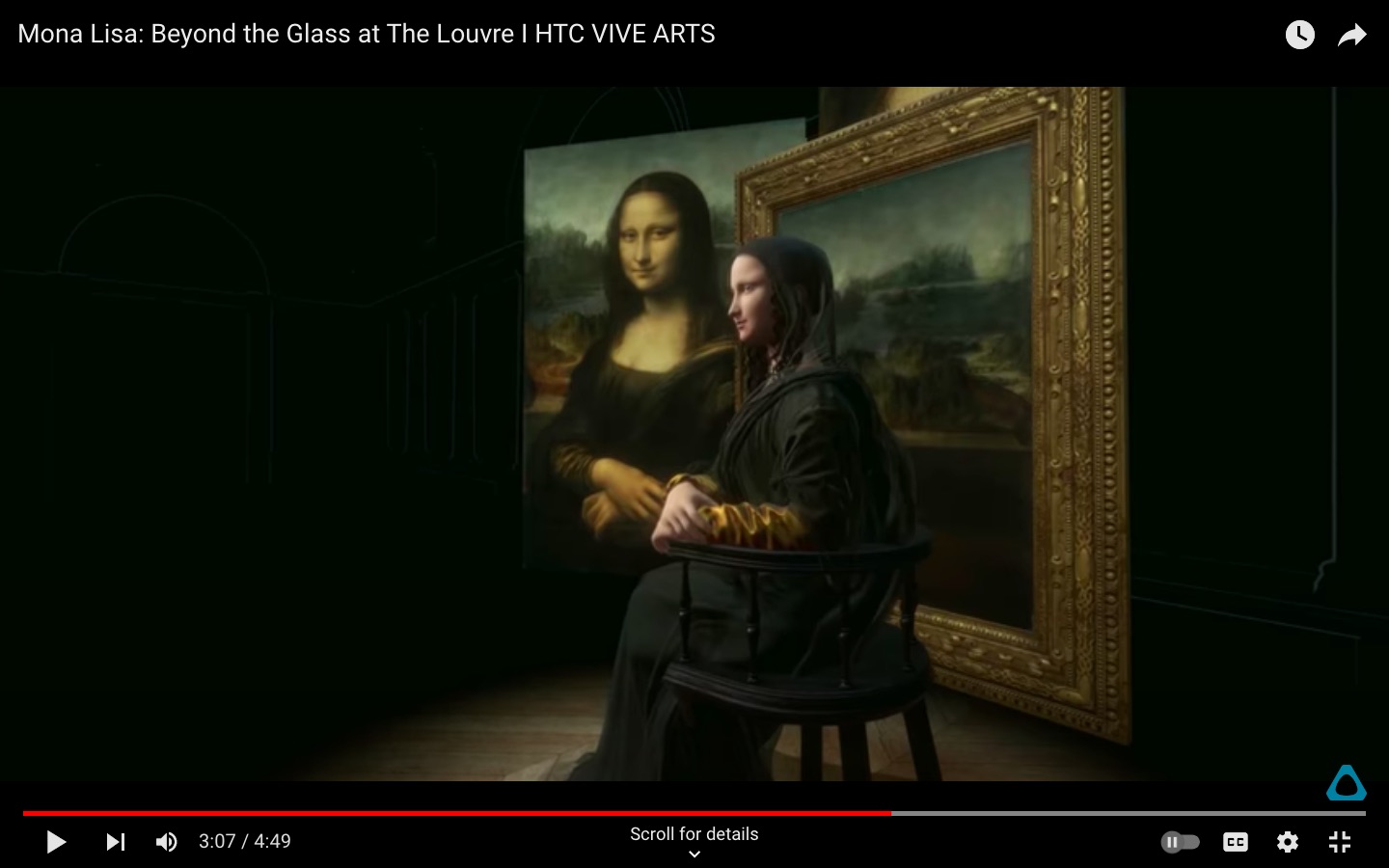

Another example of these VR films was created by the Louvre in 2020 for their Leonardo da Vinci exhibition. Titled Mona Lisa: Beyond the Glass, visitors don a headset and are placed in a dark space with various images of the Mona Lisa to give “a detailed view of [da Vinci’s] painting processes and shows how they brought his work to life.”12 (Figure 2) A full body 3D model of Mona Lisa herself is then placed in front of the painting to demonstrate her positioning, clothes, and hair, details which are not as noticeable when viewing the piece in the galleries. The experience ends with the visitor being transported to a villa overlooking a landscape based on the background of the Mona Lisa and then fly over that landscape in one of da Vinci’s flying machines. While these VR films do provide visitors with unique educational and entertaining experiences, they are limited by their lack of interactivity. The linear aspects of these films require viewers to stay mostly stationary, only moving their head to look around. By inhibiting the visitor’s freedom to explore the virtual world around them, these programs miss out on engaging opportunities to help visitors learn more about their topics.

Historical Reconstructions

Some institutions have used this technology to recreate historical settings for their objects, returning them to their original historical context. In fact, the first VR experience launched by the British Museum in 2015 placed visitors inside a Bronze Age roundhouse with 3D objects from the museum’s collection, including gold bracelets and a bronze dagger. In an interview with the BBC, the museum’s head of digital and publishing, Chris Michaels, stated that this experience “gives us the chance to create an amazing new context for objects in our collection, exploring new interpretations for our Bronze Age objects.”13 Unlike the linear VR films, this exhibit allowed visitors to move around and explore the roundhouse as they pleased. Interacting with them in their original context “further [enhanced] the real life experiences of these objects” to museum visitors, providing visitors with a better understanding of the Bronze Age.14 The result not only provided visitors with more context for the objects, but also served as a way of “helping people to remember that what they are experiencing was actually real, a way of humanising history.”15

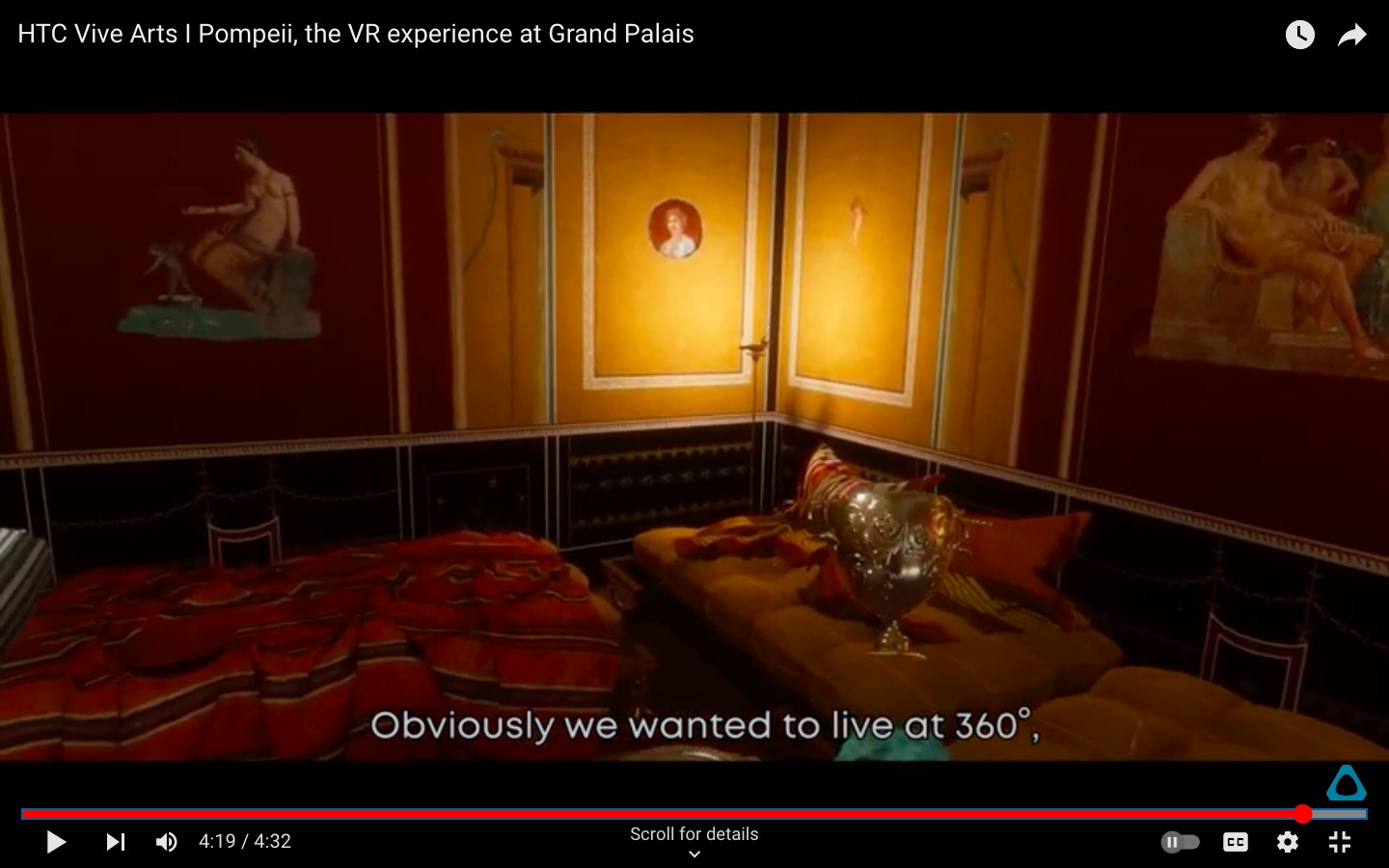

In 2017, the Tate Modern released Modigliani VR: The Ochre Atelier as part of their special exhibition of Italian artist Amedeo Modigliani. In this experience, visitors were placed in a virtual reconstruction of Modigliani’s last art studio before his death with over 60 objects and two portraits digitally recreated throughout the space. Placing these objects and portraits in this context allowed visitors to get a better understanding “about how Modigliani worked and details of his materials and techniques.”16 One of the best examples of a museum bringing context back to objects with VR historical reconstructions came in 2020 from the Grand Palais in Paris with Pompeii: The VR Experience (Figure 3). As part of their Pompeii exhibition, visitors don a VR headset that places them in the ruins of the House of the Garden in Pompeii. With the headset, they are able to switch back and forth between the present-day ruins and a reconstruction of the villa before its destruction 2,000 years ago. The faded and partial frescos become fully restored to their original splendor with furniture and artifacts placed around the room. Visitors are free to move around and interact with this space, creating a fully immersive environment that adds context to the ruins and the objects on display in the exhibition. All of these VR experiences serve as a proof of concept for the potential of VR to bring historical context back to their objects. However, criticisms of these types of contextualizing historical reconstructions may leave some museum professionals hesitant to see the potential of this technology.

Criticisms of Historical Reconstructions

Long before VR technology emerged, museums have utilized multiple methods over the past century to recreate historical settings and add historical context to their objects. The late 19th century saw period rooms emerge as “reconstructed historic interior[s] that [are] in some way representative of its past owner, era and/or region.”17 Objects in a similar artistic style as the reconstruction were then displayed in these rooms to provide visitors with historical context for the whole room. Around that same time, living history museums developed as “reconstructions of room settings or, usually, entire sites, including human beings within the displays to convey the human context as well as the physical objects.” 18 These include sites such as Colonial Williamsburg, Old Sturbridge Village, and Greenfield Village.

For the past several decades, these contextualizing museum experiences have been severely critiqued by the museum field for their historical inaccuracies that give visitors a more fictitious view of the past. Period rooms have been referred to as “a form of fiction posing as history, for much of their fabric was ‘made up’ to fit the museums’ needs” to display the objects.19 Some scholars believe living history museums present historic generalizations that “creates a Disney-like view of the past - clean, sweet, pure.”20 To these critics, these types of installations can do more harm than good in trying to help visitors understand the past. VR has not been spared from similar critiques. As far back as 1997, art historian Rebecca Leuchak believed that VR reconstructions, like period rooms, were too heavily “constructed from the ideas and values of the present” to accurately depict the past.21 More recently, virtual reconstructions of cultural sites have been critiqued for presenting a limited amount of knowledge, “as some of our cultural knowledge is neither ostensive nor directly tangible.”22 As a result, these virtual reconstructions cannot properly represent the cultures they are recreating.

The overarching idea with these critiques is that VR experiences will continue to perpetuate these historical inaccuracies and biases to museum visitors. In the case of real world reconstructions, critics tend to perceive “tourists as naïve and gullible,” passively absorbing all of the information and “unable to critically evaluate heritage displays… and incapable of recognizing inauthenticity.”23 However, when Lara Rutherford-Morrison examined living history museums and heritage sites in the UK, she found that “tourists actively and critically engage with the heritage that they consume,” demonstrating how museums tend to underestimate their visitors ability to understand possible inaccuracies within these reconstructions.24

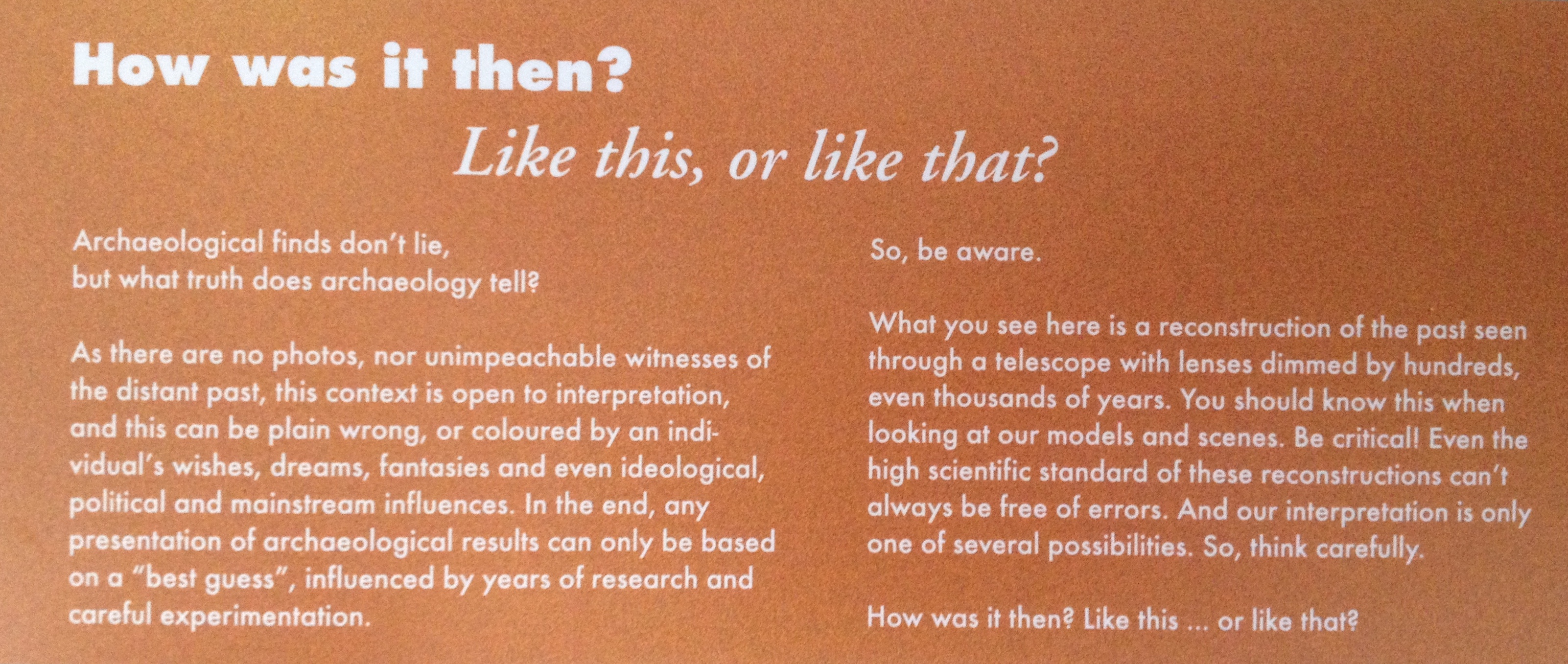

One physical museum may offer a solution for how virtual reconstructions can help visitors understand these potential inaccuracies. On the shores of Lake Constance in Germany, the Pfahlbauten Museum, or stilt house museum, contains full reconstructions of Bronze Age stilt houses based on archaeological findings along the lakeshore. Amongst these reconstructed houses, a sign is posted on a wall that asks visitors “How was it then? Like this, or like that?” (Figure 4) The sign goes on to explain that “this context is open to interpretation, and this can be plain wrong, or colored by an individual’s wishes, dreams, fantasies, and even ideological, political and mainstream influences.”25 They encourage their visitors to “Be critical! Even the high scientific standard of these reconstructions can’t always be free of errors.”26 This transparency could easily be applied to virtual reconstructions in VR. Similar labels and warnings could be stated before a VR experience begins, with this text being the first thing that appears on the headset’s screen. This allows visitors to understand the limitations of these immersive experiences while also giving them the opportunity to create their own interpretations of what they are seeing.

Figure 4

Figure 4Critics are also quick to point out how period rooms and living history museums were heavily influenced by the politics and beliefs of their founders. Some of the most popular targets for these critiques are Colonial Williamsburg, founded by the Rockefeller family, and Greenfield Village, founded by Henry Ford. As a result, these museums “reflected deliberately conservative political and social views” that strived “to valorize a national past and reaffirm the values of a preindustrial heritage.”27 American period rooms in the late 19th century had roles “in furthering nationalist self-definition” and “to protect and strengthen native traditions and standards” at a time when millions of new immigrants were seen as a threat to America’s cultural identity.28 It becomes clear that the intentions behind the creators of these museums was not placed entirely on historical accuracy, but rather as tools to promote these traditional ideals. However, the VR experiences utilized by museums today are not created by the likes of Bill Gates, Mark Zuckerberg, or Elon Musk. Instead, museum VR experiences are done by museum professionals with museological and curatorial practices to build off of. All of the VR experiences and programs mentioned earlier in this report were spearheaded and finalized by the institutions they were serving. We understand how the values and ideas of the present can influence these reconstructions, and our jobs as museum professionals is to limit as much as possible their influence on the historical context.

Even if a VR experience turns out to contain historical inaccuracies, the technology behind VR allows museums to easily fix these problems than previously possible. If new information comes forward that differs from how a museum’s period rooms or historic buildings are displayed, the museum must begin the long, painstaking process of redesigning the space. Labor and material costs for the renovations can also stack up as a project continues. When working with virtual spaces, this process overall becomes more simplified. Material costs are virtually nonexistent as everything will be done on computers. Any mistakes or errors that occur when creating the virtual world can easily be undone with a few clicks of a keyboard, while the real-world equivalent would result in major setbacks and delays. Period rooms and living history museums are also limited by the layout of the building or amount of space available to work with. VR, on the other hand, contains no such limitations and offers curators unlimited space to work with. Utilizing virtual spaces can also help preserve historic buildings and rooms when restoring them to a particular time period. For example, when Colonial Williamsburg was created, the year 1800 was established as the cutoff date for all structures in the museum.29 This meant that everything on site built after 1800 was removed and all original buildings were restored to their 18th century appearance. This “selective preservation and restoration” resulted in removing newer historical elements from structures and designating these “excluded epochs as inferior and unworthy of attention.”30 On the other hand, virtual reconstructions would allow curators to recreate a building’s 18th century appearance while keeping the physical structure intact for future research into its various architectural elements. In the end, the virtual world is significantly more malleable than our physical one, providing museums with unlimited potential to update and reinterpret these virtual spaces whenever necessary.

Conclusion

“The past is dead, and it cannot be brought back to life.”31 While written in 1974 by museum professional Robert Ronsheim, these words still ring true to those critical of contextualizing museum experiences. The historical inaccuracies and biases of period rooms and living history museums create a false sense of authenticity that makes it impossible to fully understand and recreate past structures. Virtual reconstructions in VR have faced similar criticisms. From recreating their galleries to artistic 360º films, museums have utilized VR to create a variety of experiences to engage with their visitors. However, one of the most significant potential applications for VR in museums is the ability to virtually recreate historical spaces. Despite the criticisms, VR offers museums the opportunity to take what they have learned from over a century of creating and interpreting historical reconstructions, combined with a technology with limitless creative potential, to create immersive, educational, and engaging experiences that can make the past feel more alive than ever before.

Notes

-

Henry E. Lowood, “Virtual Reality: Computer Science,” Britannica, accessed October 2, 2022, https://www.britannica.com/technology/virtual-reality. ↩︎

-

Erik Malcom Champion, Rethinking Virtual Places, (Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press, 2021), 5. ↩︎

-

Ibid, 15. ↩︎

-

Rebecca Leuchak, “Imagining and Imaging the Medieval: The Cloisters, Virtual Reality, and Paradigm Shifts,” Historical Reflections/Reflexions Historiques 23, no. 3 (Fall 1997): 367. ↩︎

-

Champion, Rethinking Virtual Places, 12. ↩︎

-

Ben Davis, “I Spent Two Hours Inside the Met’s New Augmented-Reality Experience. Here’s a Minute-by-Minute Chronicle of My Edutainment Odyssey,” Artnet News, January 13, 2021, accessed September 28, 2022, https://news.artnet.com/opinion/two-hours-inside-met-unframed-1936671. ↩︎

-

Eric Cheng, “Quality Capture and Compression in React VR,” Meta Quest Developer Center, November 17, 2017, accessed October 10, 2022, https://developer.oculus.com/blog/quality-capture-and-compression-in-react-vr/. ↩︎

-

“Experiences Entertain, Educate, and Let You Explore,” Oculus Blog, November 17,2017, accessed October 10, 2022, https://www.oculus.com/blog/new-webvr-experiences-entertain-educate-and-let-you-explore/. ↩︎

-

“Exhibition Virtual Tours,” Australian Museum, accessed October 2, 2022, https://australian.museum/exhibition/virtual-exhibition-tours/. ↩︎

-

“National Museum,” VR-All-Art, accessed October 2, 2022, https://vrallart.com/spaces/national_museum/. ↩︎

-

“Curious Alice: The VR Experience,” Victoria and Albert Museum, accessed October 2, 2022, https://www.vam.ac.uk/articles/curious-alice-the-vr-experience. ↩︎

-

“The Mona Lisa in Virtual Reality in Your Own Home,” The Louvre, February 23, 2021, accessed September 15, 2022, https://www.louvre.fr/en/what-s-on/life-at-the-museum/the-mona-lisa-in-virtual-reality-in-your-own-home. ↩︎

-

“British Museum Offers Virtual Reality Tour of Bronze Age,” BBC, August 4, 2015, accessed October 2, 2022, https://www.bbc.com/news/technology-33772694. ↩︎

-

Elizabeth Merritt, “Why VR?: Enhancing IRL (In Real Life) Experiences for Visitors to the British Museum,” American Alliance of Museums, April 28, 2016, accessed October 30, 2022, https://www.aam-us.org/2016/04/28/why-vr-enhancing-irl-in-real-life-experiences-for-visitors-to-the-british-museum/. ↩︎

-

Vilsoni Hereniko, “Virtual Museums and New Directions?,” in Curatopia: Museums and the Future of Curatorship, ed. by Phillipp Schorch and Conal McCarthy (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2019), 331. ↩︎

-

“Virtual Reality Brings Modigliani’s Final Studio to Life,” Tate Modern, November 21, 2017, accessed October 2, 2022, https://www.tate.org.uk/press/press-releases/virtual-reality-brings-modiglianis-final-studio-life. ↩︎

-

Julius Bryant, “Museum Period Rooms for the Twenty-First Century: Salvaging Ambition,” Museum Management and Curatorship 24, no. 1 (March 2009): 75. ↩︎

-

Sandra Shafernich, “On-Site Museums, Open-Air Museums, Museum Villages, and Living History Museums: Reconstructions and period rooms in the United States and the United Kingdom,” Museum Management and Curatorship 12, no. 1 (March 1993): 45. ↩︎

-

Bryant, ““Museum Period Rooms for the Twenty-First Century,” 75. ↩︎

-

Shafernich, “On-Site Museums,” 45. ↩︎

-

Leuchak, “Imagining and Imaging the Medieval,” 369. ↩︎

-

Champion, Rethinking Virtual Places, 164. ↩︎

-

Lara Rutherford-Morrison, “Playing Victorian: Heritage, Authenticity, and Make-Believe in Blists Hill Victorian Town, the Ironbridge Gorge,” The Public Historian 37, no. 3 (August 2015): 79. ↩︎

-

Ibid, 79. ↩︎

-

“How was it then? Like this, or like that?,” Pfahlbauten Museum, Unteruhldingen, Germany. ↩︎

-

Ibid. ↩︎

-

Neil Harris, “Period Rooms and the American Art Museum,” Winterthur Portfolio 46, no. 2/3 (Summer/Autumn 2012): 125. ↩︎

-

Ibid, 125. ↩︎

-

Thomas J. Schlereth, “It wasn’t that Simple,” in A Living History Reader Volume 1: Museums, ed. Jay Anderson, vol. 1, (Nashville: American Association for State and Local History, 1991), 164. ↩︎

-

David Lowenthal, “The American Way of History,” in A Living History Reader Volume 1: Museums, ed. Jay Anderson, vol. 1, (Nashville: American Association for State and Local History, 1991), 160. ↩︎

-

Robert Ronsheim, “Is the Past Dead?,” in A Living History Reader Volume 1: Museums, ed. Jay Anderson, vol. 1, (Nashville: American Association for State and Local History, 1991), 174. ↩︎