VI. Ghost in the Machine: Gender in Museum Database

- Sam Waltman, The George Washington University

In cataloguing, museums assign meaning, categorization and value to objects in their collection, creating the foundational information used to link the object to its history and the museum. While this process at first appears to have three actors, the museum, the object and the cataloger, the modern museum employees a fourth often unrecognized partner, the Collections Management System. Since the 1970s, Collections Management Systems (CMS), or Collections Databases, have transformed into the keystone tool for museum collections, a foundational piece employed by many collecting institutions.1 Databases have fundamentally changed the nature of museum cataloging, allowing museums to keep, manage and share information on scale previously unimaginable.2 Further, the very nature of relational databases allows museums to connect and organize data in ways previously unfeasible, creating a whole new dynamic between the object’s information and the museum. Despite the power of these systems to shape and manage museum information, museums often ignore the effects of the relationships drawn by collection databases in the way that they access, store and preserve information. As critical repositories of societies cultural expectations, museums often serve to enforce societal norms, particularly around gender and sexuality. Museum databases not only contain the information surrounding objects, but the cultural context both knowingly and unknowingly included by catalogers in the records. Museums must critically examine information management in collections management databases, as they have the potential to deeply embed these systems of patriarchal power, or to deconstruct the norms surrounding gender and sexuality.

Under the Hood-Relational Databases Oversimplified

Databases are a staple of life in the information era, both inside and outside the museum. Businesses, Individuals and Organizations extensively utilize databases to manage personal, public and privately held data. Museums use databases not just in collections management, but to keep track of visitor and financial data. However, despite the incredible impact that databases have on our daily lives, they are often misunderstood by society at large. Database is an extremely broad term, used to describe a variety of information management systems. At its core, a database is an organized collection of structured information, or data, typically stored electronically in a computer system.3

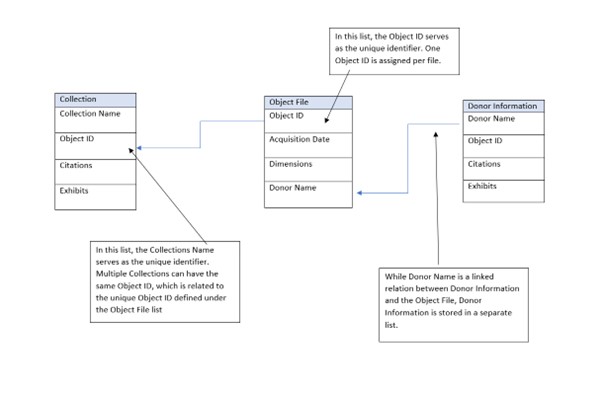

How this information is structured, stored and retrieved varies from database to database, however most museum databases are relational.4 A relational database separates the information held in a series of tables, which include distinct rows and columns.5 The database is comprised of relationships between these tables, created through the linking of object categories to create relationships between unique identifiers and other tables. 6 What this means is that a relational database is made up of a collection of relationships between information, rather than a series of distinct, individual files. An example of how this might be visualized is shown below:

Gender Inequality: A Feature, Not a Bug

Museum Collections are powerful vehicles. They are often used to explore identities, values and experiences, while also serving to provide educational insight onto large cultural issues. Museums play a central role in telling these stories, as visitors overwhelmingly trust museums as sites of cultural, historical, and artistic authority. 7 While stories told through these objects often can push societal boundaries, museums can also serve to reflect and normalize norms, stereotypes and in some cases, discrimination. In these cases, collections can knowingly and unknowingly inform viewers world view, leading to the internalization of problematic systems of power through assumptions. This is particularly problematic for issues regarding gender and sexuality, as lack of representation and casual misogynistic narratives serve to reinforce problematic norms, and in turn support and build systems of power that activity utilize gender roles to discriminate and oppress those who do not fit into the normalized boundaries set out by society. Museums not only play an active role in shaping these narratives through the exhibition of problematic pieces of art and labels, but also in how they manage the information related to objects that both fit into and fall outside of these systems of power.

The creation of categories for museum objects is not an innovation spurred by Collections Management Systems or even Collections Managers, but rather a deeply embedded practice within the museum field. As noted by Kransy and Perry, classification is a fundamental tenant of museum curation, the “creation of knowledge through identification and categorization.” 8 Museums are intentional about the information that they collect about objects. While this provides museums a great deal of freedom to describe their collections, it also provides collections professionals with the daunting task of defining what information should be catalogued about an object. Museums have limited funding, and collections departments do not have the resources or time to provide in depth information about every object in their collection. Despite this, all cataloguing involves some degree of naming, organizing and classifying objects. This process serves a real and important service to the museum, allowing for a clear organization of data that is accessible to both internal staff, researchers and casual visitors, all of which can have very different interests and needs. However, this process can also serve to disassociate objects from their original cultural context and situate them in recognizable gender and sexual norms for the cataloger.

Gender and Databases

Categorization lies at the root of these two seemingly separate pillars of the museum: the collections management database and the position of cultural authority taken by museum curators, collections and exhibits. Both serve to reinforce hierarchical structures of information in the museum. The categories in the museum database enforce strict standards for the institution to define what is and is not relevant for an object, like the position museums often play in shaping cultural expectations and norms through art and discussion of historical events. While these seem like broad, opaque forces in the museum, they are rooted in very specific choices made in what language museums use to describe their objects. It’s important to remember that computers and databases reflect the intentional or unintentional instructions of their users, and that biases in computer databases are rooted in systems of power internalized by the user. Despite museum databases being digital spaces, they are rooted in human practice and description, and have very clear effects on how databases store and retrieve data.

Case Study- RDA and The Database

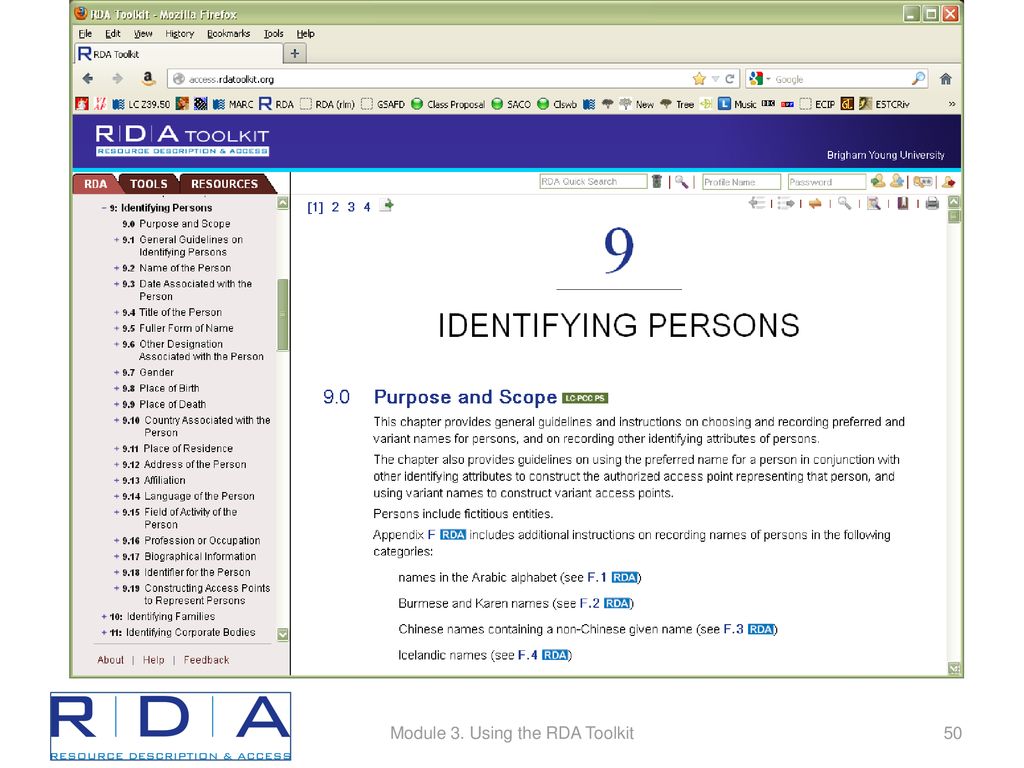

In 2010, the Library of Congress released a set of guidelines on “recording the contents and formulating bibliographic metadata for description and access to information resources covering all types of content and media held in libraries and related cultural organizations”.9 This standard, Resource Description and Access (RDA), was developed with the digital age in mind, recognizing the central role of databases in cultural institutions. 10 The RDA toolkit provided by the Library of Congress contains guidelines, instructions and recourses designed to help organizations adhere to a unified content standard in their cataloguing process, providing a clear, unified method of categorization across the museum field. Important to note is that RDA primarily acts as a content standard, meaning that it focuses primarily on the RDA is particularly interesting as it is deigned intentionally to optimize the capabilities provided by relational databases. Through its support of linked data applications, RDA aims to interlink individual museum data with larger controlled vocabularies, creating a system which functions well in creating categories and organization within a relational database.

A main selling point for RDA is its focus on providing organizations with an easily applicable content standard, which also allows a degree of flexibility for individual institutions to organize their data structures based on their needs. In fact, making the content standard more “user focused, and less anglo-centric” was a main goal in the creation of RDA. 11 This means that the description method aimed to create a degree of latitude for organizations when defining curatorial categorizations, both in digital and analog services. By providing a set of guidelines, RDA aimed to standardize the cataloguing process by providing clear, set rules of what information should and shouldn’t be included in object files. This process provides some real benefits to cultural institutions seeking to standardize their data sets, especially those that intake large collections with less resources. The development of RDA was a response for a lack of clear, standardized categorizations in the museum field, fulfilling a pressing and important gap in data standards in the digital age. However, the development of the standards closely reflected previous understandings of categorization within the museum field, specifically around gender.

As highlighted by Biley and Drabinsky (2014), RDA employees the use of binary language when attributing gender to an authority file, creating a system of gender norming throughout the descriptive practice. 12 This can be seen most particularly in authority files, which asks catalogers to assign a gender tag to author or creator. In theory, this provides an easily accessible data point for researchers to utilize while searching the database. Problematically, the rule governing this aspect of cataloging, RDA rule 9.7, asks catalogers to assign an “appropriate” term for the gender field. While the term “appropriate” implies that researchers do not have to use “male” or “female” as identifiers, it still demands that a firm label be affixed to an object, which might have a more complicated relationship with gender and sexuality. In the RDA form of cataloging, gender serves as a unique identifier in a relational database, a guiding tool used to sort and search through information. Affixing a static, singular gender identity to an author or creator not only is problematic for individual files, but also data sets linked to this unique identifier. Singular gender identities are not just imposed on singular sets of records or collections, but rather on the database as a whole.13

To be clear, the issue presented by RDA is not the inclusion of gender in museum collections management software. Gender can be an important contextualize of an individual’s identity and experiences and can serve a key role in understanding objects or overarching stories present in collections. Further, databases serve as critical links between large museum collections and communities whose identities have often been marginalized in traditional historical narratives, both inside and outside the academic community. These complex issues of gender have often been written out of history through purposeful omission, erasing critical aspects of people’s lives and identities in order to prevent more complicated discussions surrounding gender and sexuality. By removing gender from databases, museums would contribute to this legacy of erasure, electing to disengage from peoples’ often complicated relationship with gender and sexuality rather than embracing the discussion. When done correctly, gender in databases can serve to connect those searching for these stories inside the collection. What is an issue, however, is the inclusion of singular categories that reinforce traditional heteronormative understandings of gender and sexuality as static, unchanging categories that remain permanently fixed. As concluded by Biley and Draminsky, it would not matter how many options a cataloger was provided with, as long as the core of the cataloging process around the selection of a singular gender identity from a fixed list, all data in the CMS becomes centered around this restrictive view of gender and sexuality.

The Ghost in the Machine: Relational Databases

While Biley and Dramisky’s work primarily focuses on RDA as a cataloging process, the issue is much more fundamental than specific choices made by one cataloging method. As pointed out by the Library of Congress, RDA was envisioned to synergize with museum databases, acting as a cataloging tool for the digital age. 14 Relational databases that museums utilize are based on systems of standardization, lists are defined by unique identifiers and consistent categories, which link together to create the information management tools that museums rely on. It’s no accident that museum database software has led to a rise in homogeneous nomenclature in the field, the digital layout of a relational database inherently revolves around the creation of these standardized lists for the linking of data. Relational databases were designed with categorization in mind, to easily store, query and filter information for end users. Relational databases that museums utilize are based on systems of standardization, lists are defined by unique identifiers and consistent categories, which link together to create the information management tools that museums rely on.

It’s no accident that museum database software has led to a rise in homogeneous nomenclature in the field, the digital layout of a relational database inherently revolves around the creation of these standardized lists for the linking of data. At first glance, this data management model seems extremely convenient for museums seeking to categorize their collection. However, as discussed, this process of categorization foundational to the museum field often serves to place or incorporate objects and stories into dominant, heteronormative gender identities. The failure of RDA to provide a dynamic vocabulary that reflects the constant fluctuation of gender identity lies not in its failure to understand collections management systems or gender identities, but rather how well the cataloging standards are constructed to fit within the nature of a relational database. On the surface, RDA appears to be based around the cataloger’s relationship with the objects being cataloged. However, on a deeper level, RDA revolves around the cataloger’s relationship with the tool they use to catalog, with the database playing an active role in defining and shaping these processes. While on the surface issues revolving around the institution of heteronormative terms and beliefs in cataloging processes appears to revolve around the user, the relational database acts as an active player, an invisible specter which prevents a fluid and changing definition of gender from being utilized by the very nature of its being. To exorcise this ghost from collections management software, museums professionals must dive deeper than simply redefining cataloguing terms and consider a data management model based on complexity and overlapping identities, rather than on fixed categorization.

Building a New Type of Database

The creation of a new type of museum database is a task more easily identified than completed. Setting aside the logistical issues of migrating large museum collections, as well as ethical issues related to the equal distribution and access of technology to smaller and less funded institutions, there is the considerable challenge of designing a software that reflects both the collections management needs of an institution. This logistical challenge should not stop museums from engaging in the issue. Continuing to employ systems simply because they work well enough maintains systems of gender normativity in the museum space, continuing a long and troubling history of academia aiding in de-queering history. Instead, acknowledging the reality that immediate improvements to language used in current collections management systems are needed in addition to the continual goal of developing new information systems not based on categorization is necessary to make the field a more equitable place, now and in the future. For both immediate and long-term projects working on creating these new database systems, empowering LGBTQIA+ communities to be decision makers in design and implementation processes is essential.

As discussed, the relational databases that museums traditionally utilize rely heavily on the categories defined by users. For standardization processes, adopting a unified lexicon (such as RDA) is necessary for creating organized databases. While this process is inherently problematic, there are immediate solutions to ensure that these categories utilize terms and language accepted by LGBTQIA+ communities. As noted by the Trans-Metadata collective, the current descriptive practices for trans and gender fluid people inside of GLAM spaces presents the risk of being misnamed or outed, potentially opening individuals to harm or violence. 15 The collective published a cataloging standard “Metadata Best Practices for Trans and Gender Diverse Resources”, which seeks to provide best practices for “for the description, cataloguing, and classification of information resources as well as the creation of metadata about trans and gender diverse people.”16 By providing a set of relatively easily accessible standards for institutions, the document provides a road map for improving cataloging practices already utilized by museums. As pointed out by the Trans-Metadata collective, “Perfect is not always possible, and sometimes you just have to do your best”. 17 While this form of categorization runs into the same issue of providing a static identifier for gender, which is often fluid and complex, it at least provides a baseline for museums to start to implement within currently existing databases. While recognizing these databases are not perfect, empowering LGBTQIA+ individuals to make decisions about what categorizes are used within them provides a necessary middle ground for progressing the field.

While empowering LGBTQIA+ professionals to shape databases in ways that utilize preferred terminology is an important step towards creating collections management systems that reflect the complexity of gender, working towards systems of information management that are responsive, rather than static, is a necessary step for the field. In her work on diverse systems of knowing in the museum, Erin Canning suggests moving towards an event centric information data model. 18 Essentially, the suggestion revolves around basing the management of information in museum databases not around physical objects, but rather around the context and knowledge surrounding them. What Canning provides is not a fully functional framework for a new model of data management. However, it does call attention to different ways of constructing database to emphasize different types of data and organize it in ways that do not revolve around firm categorization into distinct, unchanging categories. Shifting the mindset of the museum away from collections databases to simply manage physical objects to collections management systems as a way to incorporate and preserve complex, changing stories around topics like gender is necessary step for the evolution of the field. The solutions are frustratingly vague and seemingly out of reach. However, the rethinking of the use of databases in managing museum collections holds boundless potential for enabling LGBTIA+ communities to access and preserve critical knowledge, stories, and histories. By opening the field to alternatives in collections management systems, the field also provides space towards moving past a legacy of upholding gender norming ideals, and towards acting as a critical resource for challenging systems of power and identity.

Notes

-

Parry, R. “From the ‘Day Book’ to the ‘Data Bank’: The Beginnings of Museum Computing,” Recoding the museum: digital heritage and the technologies of change. (London: Routledge, 2007), 15-31. ↩︎

-

Ibid ↩︎

-

What Is a Database?,” Oracle, accessed October 6, 2022, https://www.oracle.com/database/what-is-database/. ↩︎

-

Examples of Relational Museum Databases include Past Perfect, TMS, Emu, and MimsyXG. ↩︎

-

Harrington, Jan L. Relational Database Design and Implementation Clearly Explained. 3rd ed. Amsterdam;: Morgan Kaufmann/Elsevier, 2009. Print. ↩︎

-

Ibid ↩︎

-

American Alliance of Museums, “Museum Facts and Data,” (AAM Press, 2020). ↩︎

-

Elke Krasny, Lara Perry. “Unsettling Gender, Sexuality, and Race: ‘Crossing’ the Collecting, Classifying, and Spectacularising Mechanisms of the Museum.” Museum International 72, no. 1-2 (2020): 130–139. ↩︎

-

“About.” RDA Toolkit. Accessed September 17, 2022. https://www.rdatoolkit.org/about. ↩︎

-

Ibid. ↩︎

-

Ibid. ↩︎

-

Billey, Amber, Drabinski, Emily, and Roberto, K.R., “What’s Gender Got to Do With It? A Critique of RDA Rule 9.7” (2014). University Libraries Faculty and Staff Publications. 19. ↩︎

-

Ibid, 21. ↩︎

-

Ibid, 19. ↩︎

-

The Trans Metadata Collective, Burns, Jasmine, Cronquist, Michelle, Huang, Jackson, Murphy, Devon, Rawson, K.J., Schaefer, Beck, Simons, Jamie, Watson, Brian M., and Williams, Adrian. “Metadata Best Practices for Trans and Gender Diverse Resources”. Zenodo, June 22, 2022. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.6687044. ↩︎

-

Ibid ↩︎

-

Ibid ↩︎

-

Canning, Erin “Making Space for Diverse Ways of Knowing in Museum Collections Information Systems” (ICOM, August 2020) ↩︎