III. Patterns of Engagement

- Samantha Bateman, The George Washington University

From the moment we are born to the day we die; we are surrounded by clothing. Clothes have become an integral part of the human experience, varying across time, culture, and geography. Clothing has the “power to alter perceptions and opinions, to disguise and interpret, to heighten or lessen the wearers’ very sense of themselves for better or for worse.”1 Therefore, it is unsurprising that the global fashion industry will be valued at $1.7 trillion in 2022.2 As fashion and clothing are so intertwined with our daily lives, it makes sense that, as a society, we are fascinated by the aesthetics, history, and production of clothing. Many museums collect, preserve, and store clothing, accessories, and objects relating to or documenting clothing production. To reconnect “museum objects and knowledge to global flows of culture and information,” museums have developed online collection databases allowing the meaning behind the objects to come forward and be represented.3 Yet, digitization efforts have not engaged fashion collections in the same way as other objects in museums.

To digitize clothing to their full potential, museums should not just preserve the garments through photos or three-dimensional(3D) imaging but go beyond that by creating step-by-step instructions on how the recreate the clothing. By providing instructions to recreate garments in a fashion collection, museums can help preserve the object and engage with a broader audience by reconnecting the garment’s social past. This paper will first discuss the problems museums face regarding the digitization of fashion collections. Then the paper will describe three methods museums have used to digitize fashion collections and the opportunities and obstacles of each method. Subsequently, the paper will explore the importance of creating patterns of garments in fashion collections to preserve the object while engaging visitors.

Overview of fashion collections

Fashion collections at a museum include clothing and accessories spanning centuries. The Costume Institute at the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s (MET) collection has “more than thirty-three thousand objects [over] seven centuries of fashionable dress and accessories for men, women, and children, from the fifteenth century to the present.”4 Another museum with an extensive fashion collection is the Victoria and Albert Museum (V&A), with a collection spanning five centuries containing “rare 17th century gowns, 18th century ‘mantua’ dresses, 1930s eveningwear, 1960s daywear and post-war couture.”5 These two museums are an example of how vast fashion collections are and that the collection does not have the constraints of time, the original owner’s gender, or the origin of an object. This wide range makes working with fashion collections complex, as a shift dress from the 1960s is easier to put on a mannequin for display than an eighteenth-century gown. This paper will focus on historical garments dated before the twentieth century because garments from his period illustrate the problems fashion collections face when digitizing their collection.

Digitizing Fashion Collections: Challenges

Over time fibers that make up historical clothing weakens and often break, which is part of the natural life cycle of a garment. Even with standard wear and aging, factors such as light exposure, humidity, temperature, pests, physical forces [such as], and pollutants make historical clothing vulnerable.6 The composition of the textile, such as the type of fiber, the structure of the fabric, and the dyes or embellishments, can also cause damage, which requires urgent conservation and presentation before the garment becomes too delicate to display.7 An excellent example of a combination of external factors reacting to a specific textile is weighted silk, which was used in the nineteenth century. Weighted silk is silk fabric that has been treated with metallic salts to improve the drape of the fabric and restore the weight of silk, which enhances the dying process.8 Over time the metal dyes become photosensitive and deteriorate, causing the fabric to look shattered (fig. 1).9 The example of weighted silk shows that one or more external factors can cause irreparable damage to clothing in a museum collection.

Figure 1

Figure 1Museums utilize digitization as a preservation method to catalog the current state of a garment, track the deterioration of fibers, and give the public access to objects they would not have a chance to see. Like many digitization projects, digitization uses a lot of resources and funding to plan and complete. The process of digitizing a fashion collection is outlined by Tekara Shay Stewart and Sara Marcketti as “objects [are] selected, they [are] then placed on dress forms, photographed and saved in raw format, and then the photos [are] edited and uploaded as low resolution jpeg files to the website.”10 The complexity of digitizing a fashion collection is in selecting the objects and placing the garments on the dress form. When choosing objects, a large amount of space is needed to unbox the garments from storage onto a flat table to see what the garment needs to have before the garment is placed on the dress form.11 To aid in dating and the determination of what under support is necessary for the garment before it goes on the dress form, staff utilize the resources found in books, such as Janet Arnold’s Patterns of Fashion series, which is a collection of line drawings of the inside and pattern of a garment made through reverse patterning.12

Due to the delicate nature of historical clothing, the dress forms need to have the proper under support not just to create the original shape of the garment but to help prevent stress on the fibers. Dress forms that do not provide adequate support can cause the garments to warp due to gravity, and “mounting a costume on a [dress form] can involve a great deal of manipulation; as such, this type of handling can result in undue stresses on certain parts of the garment.”13

Digitizing Fashion Collections: Methods

Clothing in museum collections is often stored relatively flat but needs to be displayed three-dimensionally. This quality has led to many museums using different digitization methods for their respective fashion collections. Currently, there are three ways to digitize fashion collections: multiple high-resolution images, 3D imaging of a garment, and reverse patterning by analyzing a garment.

Multiple high resolution images

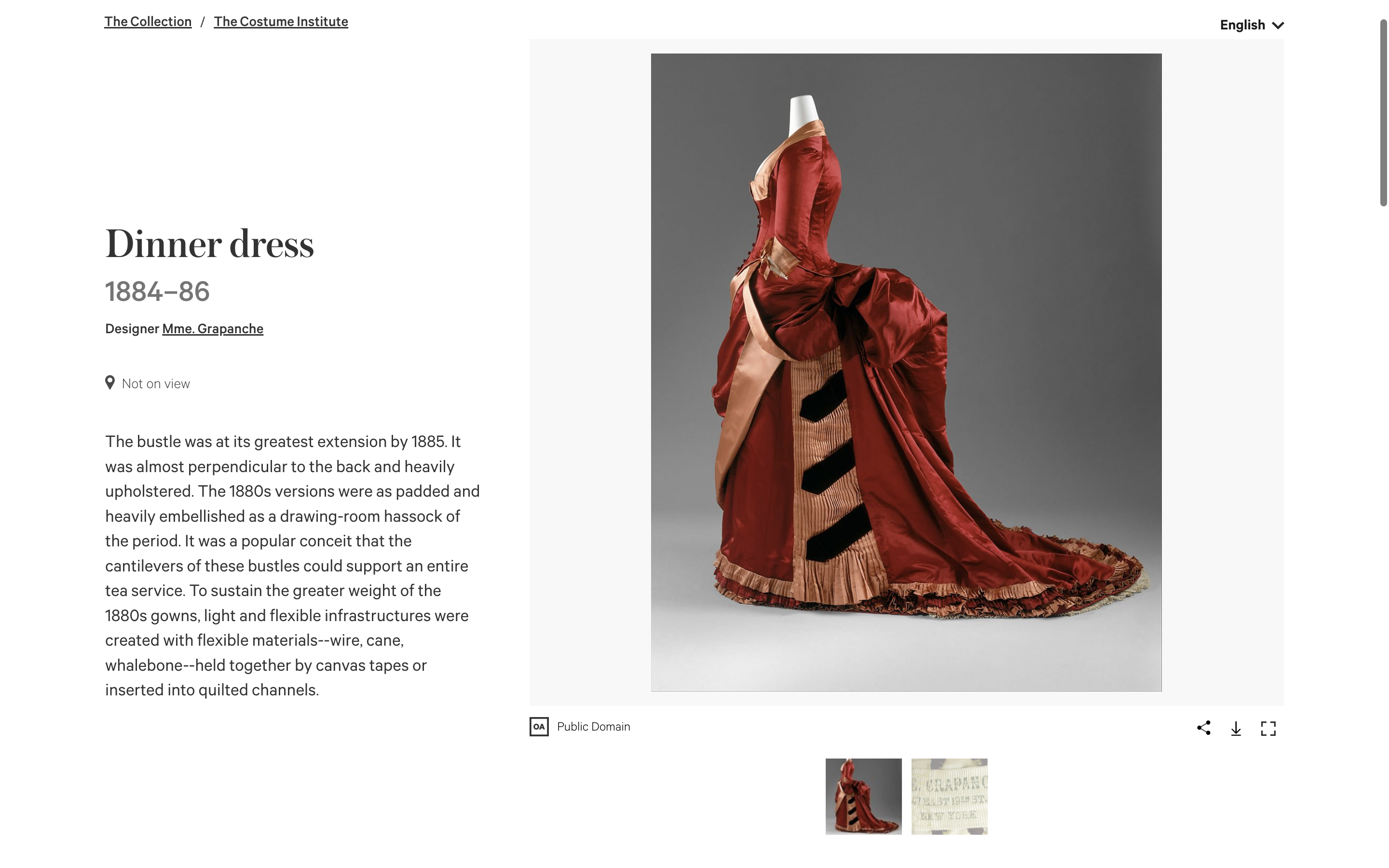

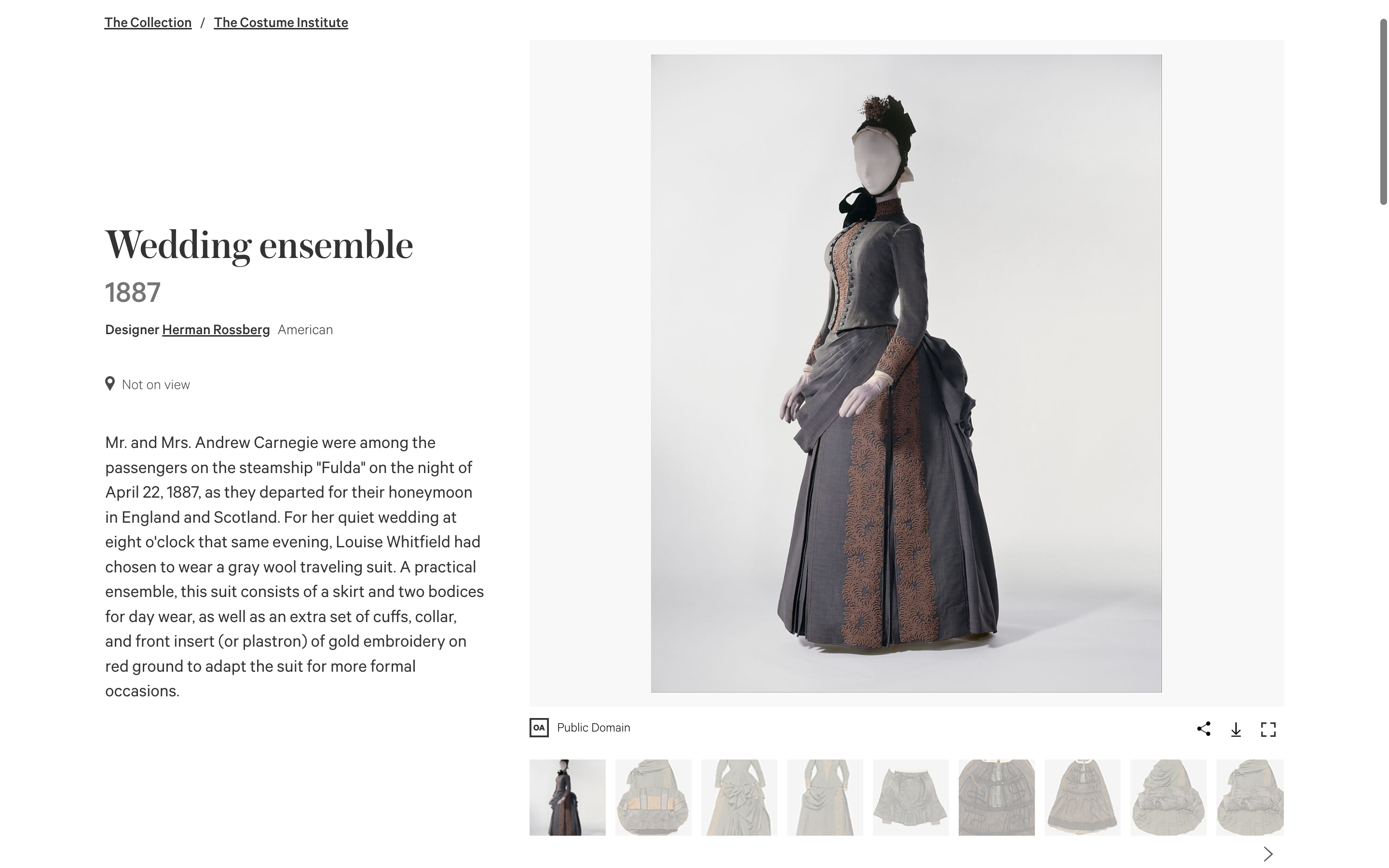

The most common method for digitizing fashion collections is simply taking multiple images. This form of digitization involves readily accessible technology and enables a visitor to explore a three-dimensional garment in a two-dimensional format through various viewpoints, giving viewers an idea of what a garment looks like.14 However, this form of digitization is most successful when the garment’s silhouette is correct, the resolution of the images is high, and all of the details of the garment are captured. We can look at two examples from the MET’s Costume Institute online collection to compare a highly successful use of this approach with one that is less so. There are two late nineteenth-century gown ensembles in the Costume Institute’s digital collections database, which shows the pros and cons of using multiple images. The first is the 1887 wedding ensemble worn by Louise Whitfield Carnegie (fig. 2). Thirty-nine photos from different angles show the complete garment with the correct silhouette, close-up images of the garment, the inside of the garment, and the garment on and off the dress form. The second example is of a dinner dress from 1884-1886 that shows the limitations of multiple images (fig. 3). The gown ensemble only has two images: the first is a side view of the dress showing the length of the bustle, and the second image is of the designer’s tag with no image of the front or back of the dress. Capturing clothing through multiple images is an accessible form of digitizing fashion collections but is limited to the amount of time and pictures taken of the garment.

Figure 2

Figure 2

3D Imaging

Besides the multiple high-resolution images of historical clothing, a few museums, such as the Royal Cornwall Museum (RCM), have used 3D imaging to digitize their collection. To complete the project, the RCM worked with Purpose3D, a British tech startup focusing on 3D imaging of fashion collections and making the files readily available as digital downloads.15 RCM decided to use 3D imaging because the imaging process would help make their costume collection more accessible and immersive.16 After scanning the object and processing its 3D image, the RCM and Purpose3D uploaded the collection to Sketchfab, a 3D modeling platform. 3D imaging of fashion collections allows researchers, designers, and fashion enthusiasts to explore the shape, silhouette, and details of a garment without the need to handle the physical object. However, 3D imaging isn’t perfect. In this case, garments that should have been paired together, such as the wine-red dress ensemble, were separated in the scanning process but not put together in the final 3D rendering (see below). The 3D imaging only focused on the outside of the garment. By only focusing on the exterior of the garment, it is difficult to understand the construction and any additional material used to create the garment. 3D imaging allows audiences to explore a piece of a fashion collection without the potential of damaging the original objects.

Reverse patterning through analysis

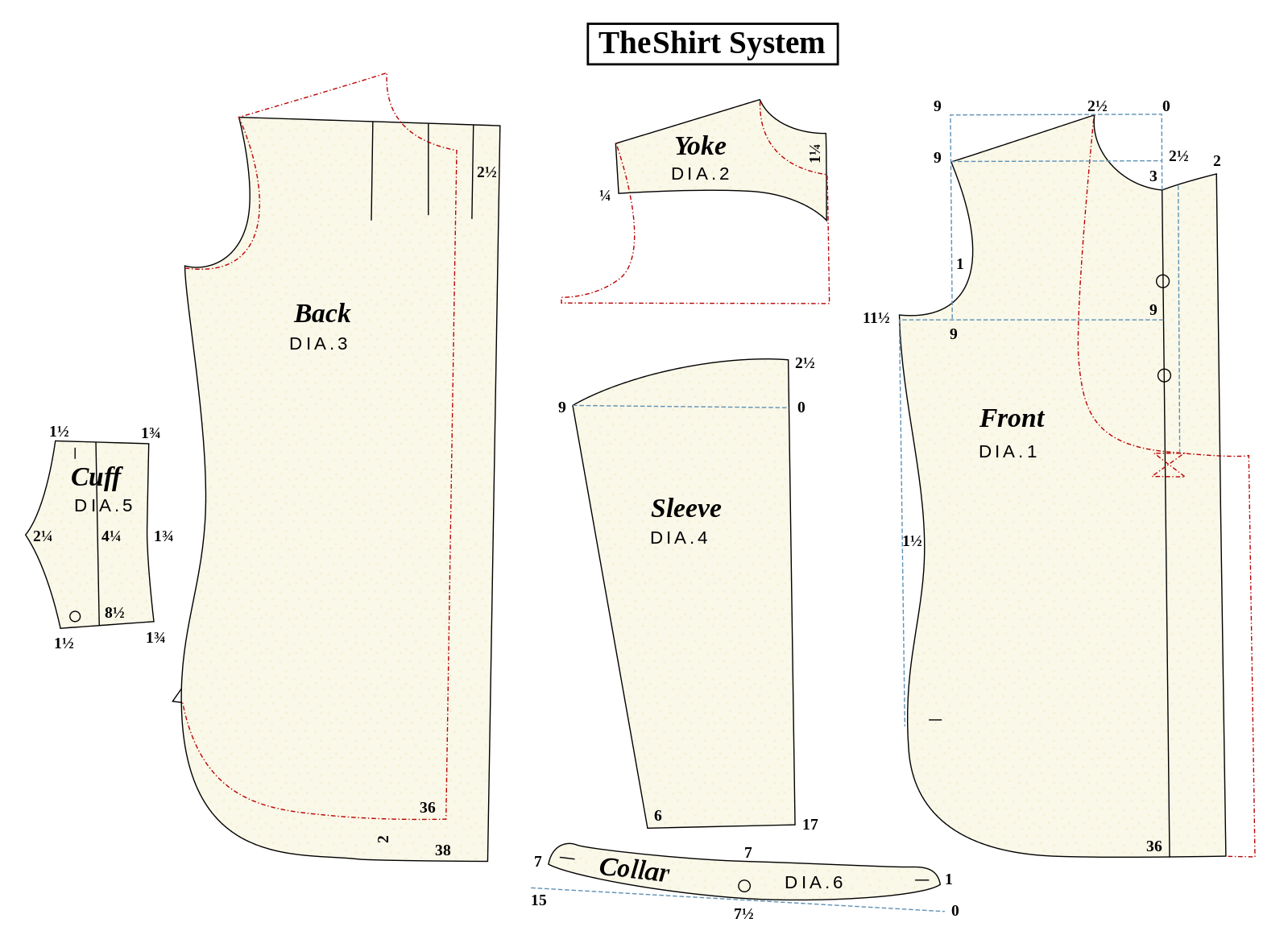

All clothing, modern or historical, is made from a pattern (fig 4). A pattern is defined as a “template from which the parts of a garment are traced onto woven or knitted fabrics before being cut out and assembled.”17 Patterns are an integral part of fashion design and garment construction. Over time methods have been developed to take an already constructed garment and transform the garment back into its pattern pieces to be duplicated. This process has many names as it is not a formal technique used in fashion design; therefore, I will refer to this technique as reverse patterning. As all clothes are made from flat pieces of fabric, the complexity of reverse patterning is due to the specialized skill of pattern drafting and the specific knowledge of clothing construction. Having the pattern of a historic garment gives more information than what is included in multiple high-resolution photos and 3D imaging, as the construction of a garment is just as important as the exterior aesthetics.

Figure 4

Figure 4A museum that has used reverse patterning for historical clothing in its collection is the Los Angeles County Museum of Art (LACMA). The ‘Pattern Project’ is a free PDF pattern archive of a selection of historical clothing from two past exhibitions Fashioning Fashion: European Dress in Detail 1700-1915 and Reigning Men: Fashion in Menswear 1700-2015. The free PDF of each garment includes a “scaled pattern of an extant fashion object from the collection, a description with historical context and object-based observations, overall and detail images, and instructions for construction of the garment.”18 It was noted in the description of the ‘Pattern Project’ states that:

The cut of a garment can speak volumes about its wearer, maker, place, and time. This resource is a means to make this information freely available to enthusiasts and scholars alike, while continuing the museum’s mission for greater access and meaningful engagement to significant works of art in the collection.19

To create a pattern through reverse patterning, the garment must be handled beyond the garment being placed on a mannequin to understand the construction methods. The museum would have to create directions for constructing the garment based on the reverse patterning process.

The benefits of reverse patterning and analysis of composition

There are two reasons why reverse patterning can benefit fashion collections. The first is that by having the pattern, the garment can be preserved further through having the ability to recreate the garment. Although handling historical clothing can damage a historical garment, the museum is preserving the piece beyond its life through reverse patterning. By creating a digital pattern of a historical garment, a concrete record will be made of how the garment is constructed, adding to the multiple high-resolution images or 3D imaging of the garment. If something does happen and the object is damaged, the museum can continue caring for part of the object by having a pattern of the object. By preserving the physical garment and information about the garment by recreating the pattern, we can gain insights into the practices and processes involved in constructing the garment. Reverse patterning requires great care in handling the garments, knowledge of garment construction, textile structure, and fashion history, and combining this knowledge into a readable pattern with instructions.20 While completing the pattern of a boy’s frock (fig. 7), Thomas John Bernard noted that the garment was made by a “talented home seamstress [as] the pieces did not line up exactly, and sometimes the fabric is slightly off-grain.”21 Without the prior knowledge of garment construction and pattern making, Bernard would not have noticed the slight differences in the garment. From his analysis, future pattern drafters and sewers can use the knowledge from the LACMA Pattern Project to inform their own studies and practice.

Secondly, as garments are social objects, having the pattern of garments in a fashion collection can engage different groups of people and visitors in a new way. The concept of social objects was initially used by Jyri Engeström in 2005, who stated that a social object “connects the people who create, own, use, critique, or consume it.”22 Nina Simon pushes Engestrom’s definition further by stating that social objects “are engines of socially networked experiences, the content around which conversation happens” and that “people can connect with strangers when they have a shared interest in specific objects.”23 With these definitions in mind, clothing falls into the category of a social object. Many fashion collections in academic settings focus on clothing’s broader connection to the world through the accessibility of hands-on interaction and analysis of the construction of garments by students and designers.24 Museums are noted to be inaccessible to students and designers by not allowing hands-on interaction with fashion collections.25 The stories and connections to the time and world around a similar garment in a museum fashion collection are lost or reduced to its aesthetic qualities, unlike its counterpart in an academic fashion collection.

Although fashion and clothing are very social objects, museums often do not use the social aspects to engage a more diverse audience. Digitization allows museums with fashion collections to open their collection, allowing people “to create, share, and connect around it.”26 Through understanding the construction and history of a garment using the technique of reverse patterning, the social past of garments in fashion collections is amplified, allowing them to become social again. The garments can then serve as a “contrast to an increasing fast fashion production and to the over-consumption…that has come to structure much of our relation to garments.”27 An example of the contrast between the clothing that makes up a museum fashion collection and modern clothing is the boy’s frock from the LACMA ‘Pattern Project’. Through reverse patterning the garment was found to be made from a previous garment by a home seamstress trying to reuse the fabric as it is an expensive fine embroidered cashmere.28 Reusing clothing to create a new garment is rare as our clothing has been made to be disposed of because of fast fashion and overconsumption. This is one example of how reverse patterning can reengage the social aspects of museum fashion collection objects.

Conclusion

Through multiple high-resolution images, 3D imaging, and reverse patterning, fashion collections transform from an encyclopedia focusing on aesthetics to one focusing on the social and human experience of clothing. These three methods each show a different complexity of fashion collections and how digitization helps preserve the physical garment and the intellectual knowledge of the garment’s construction. Reconnecting these two aspects of fashion collections can help people relate to and understand history in a new and more intimate way. This new way of looking at clothing removes the mysticism of the modern fashion industry and can go on to help inform our choices in the clothing we wear. Because one day, our clothes will be behind a glass wall in a museum exhibit describing our relationship to the world.

Notes

-

Lydia Edwards, “Introduction,” in How to Read a Dress: A Guide to Changing Fashion from the 16th to the 20th Century (London: Bloomsbury, 2017), 12. ↩︎

-

Sky Ariella, 28 Dazzling Fashion Industry Statistics [2022]: How Much Is The Fashion Industry Worth (Zippia, October 3, 2022), https://www.zippia.com/advice/fashion-industry-statistics/. ↩︎

-

Suse Anderson, “Some Provocations on the Digital Future of Museums,” in The Digital Future of Museums: Conversations and Provocations (London: Routledge, 2020), 20, https://doi.org/10.4324/9780429491573. ↩︎

-

“The Costume Institute,” The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Accessed November 21, 2022, https://www.metmuseum.org/about-the-met/collection-areas/the-costume-institute. ↩︎

-

“Fashion,” Victoria and Albert Museum, Accessed November 21, 2022, https://www.vam.ac.uk/collections/fashion ↩︎

-

Canadian Conservation Institute, “Caring for Textiles and Costumes,” in Preventive conservation guidelines for collections (Government of Canada / Gouvernement du Canada, January 8, 2020), Accessed November 21, 2022, https://www.canada.ca/en/conservation-institute/services/preventive-conservation/guidelines-collections/textiles-costumes.html. ↩︎

-

Canadian Conservation Institute, “Caring for Textiles and Costumes.” ↩︎

-

Canadian Conservation Institute, “Caring for Textiles and Costumes.” ↩︎

-

Canadian Conservation Institute, “Caring for Textiles and Costumes.” ↩︎

-

Tekara Shay Stewart and Sara B. Marcketti, “Textiles, dress, and fashion museum website development: strategies and practices,” Museum Management and Curatorship 27, no. 5 (December 2012): 521, DOI: 10.1080/09647775.2012.738137. ↩︎

-

History Trust of South Australia, “Preparing Historic Costume for Digitisation,” YouTube, June 26, 2022, 0:07 to 0:49, https://youtu.be/lDYdtJx7B3s. ↩︎

-

History Trust of South Australia, “Preparing Historic Costume for Digitisation,” 0:49 to 1:33. ↩︎

-

Canadian Conservation Institute, “Caring for Textiles and Costumes.” ↩︎

-

Stewart and Marcketti, “Textiles, dress, and fashion museum website development,” 531. ↩︎

-

“About Us,” Purpose3D, Accessed October 16, 2022, https://purpose3d.co.uk/about-us/ (site discontinued). ↩︎

-

Cornwall Museum Partnerships, “Beyond Digitisation at the Royal Cornwall Museum,” YouTube, October 20, 2021. 2:30-2:45, https://youtu.be/kfXw5cgx32g. ↩︎

-

“Pattern (sewing),” Wikimedia Foundation, Last modified November 6, 2022, 01:47 (UTC), https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pattern_(sewing). ↩︎

-

“Undertaking the Making: LACMA Costume and Textile Pattern Project,” Los Angeles County Museum of Art, Accessed November 22, 2022, https://www.lacma.org/patternproject. ↩︎

-

“Undertaking the Making,” Los Angeles County Museum of Art. ↩︎

-

Clarissa M. Esguerra, “Undertaking the Making: Reigning Men Pattern Project,” Unframed (blog), Los Angeles County Museum of Art, March 30, 2016, https://unframed.lacma.org/2016/03/30/undertaking-making-reigning-men-pattern-project ↩︎

-

Amy Heibel, “Fashion Your Own Fashion,” Unframed (blog), Los Angeles County Museum of Art, January 11, 2011, https://unframed.lacma.org/2011/01/11/fashion-your-own-fashion ↩︎

-

Nina Simon, “Social Objects,” in The Participatory Museum, (Santa Cruz: Museum 2.0, 2010), 129. ↩︎

-

Simon, “Social Objects,” 127-128. ↩︎

-

Kelly Cobb, Belinda Orzada and Dilia López-Gydosh, “History is Always in Fashion: The Practice of Artifact-based Dress History in the Academic Collection,” Journal of Textile Design Research and Practice 8, no. 1 (2020): 7, DOI: 10.1080/20511787.2019.1580435 ↩︎

-

Clare Sauro, “Digitized Historic Costume Collections: Inspiring the Future While Preserving the Past,” Journal of the American Society for Information Science and Technology 60, no. 9, (September 2009): pages, DOI: 10.1002/asi.21137 ↩︎

-

Nina Simon, “Principles of Participation,” in The Participatory Museum, (Santa Cruz: Museum 2.0, 2010), 3-4. ↩︎

-

Louise Wallenberg, “Art, life, and the fashion museum: for a more solidarian exhibition practice,” Fashion and Textiles 7, no. 1 (December 2020), https://doi.org/10.1186/s40691-019-0201-5. ↩︎

-

Los Angeles County Museum of Art, “Boy’s Frock” in Undertaking the Making: LACMA Costume and Textiles Pattern Project, Los Angeles County Museum of Art, Accessed November 22, 2022, https://www.lacma.org/patternproject. ↩︎

| words