XI. Web Accessibility for Individuals with Disabilities in Digital Collections: A Case Study of the Smithsonian National Museum of American History

- Elsa Tolman, The George Washington University

With the changes in society and available tools over the last decades, digital technologies have become one of the main gateways for museums “to provide access to content and collections” for their visitors and communities.1 Societal expectations and the growing abilities of digital tools have played a role in the changing relationship of museums and technology during this time, such as the services they provide to the public. This has produced a range of new resources, digital collections of some or all of the objects within a museum’s collection being one of them. Though such resources have provided access to a large number of people, especially during the COVID-19 lockdowns, research has shown that museums have found difficulty in improving their website’s “discoverability [and] visibility,”2 all of which can be improved with the inclusion of web accessibility, as discussed later in this paper. Through the use of digital technology, museum information and objects can theoretically be available to everyone,3 but limitations in the layout and code of a website can lead to an inability of numerous groups to access museum resources.

One group negatively affected by these limitations are individuals with disabilities, such as people with auditory, cognitive, neurological, physical, speech, and visual disabilities.4 In ways that non-disabled individuals may not realize, the structure and code of a webpage can have an enormous impact on the ability of this group to receive an equal quality of information and experience. Though the Web theoretically provides unprecedented access to information and interactions for individuals with disabilities, the reality is that many webpages have barriers that limit their access and ability to experience the offered resources.5

What is Web Accessibility, and Why Does It Matter?

Web accessibility for individuals with disabilities “means that websites, tools, and technologies are designed and developed so that people with disabilities can use them. More specifically, people can: perceive, understand, navigate, and interact with the Web [and] contribute to the Web.”6 It means, in the most basic sense, that individuals with disabilities can use the Web.7 As a point of reference, web accessibility is described by some as a subset underneath Universal Design, a framework that promotes a focus on all users at every point–a “Human-Centered design.”8 Web accessibility, specifically, is a quality attribute given to different webpages on the Web that allow for equitable access no matter an individual’s physical abilities and context at the time of interaction.9 When it comes to modern technologies and digital tools, this especially means that websites must be formatted to allow for different types of assistive technologies to express an equitable experience, which has much to do with its code.10 Assistive technologies include software such as screen readers that read the webpage’s text or alt text aloud, screen magnifiers that allow for a webpage to be zoomed into to enlarge the text or content, and voice dictation software that allows users to have their verbal words written as text.

Because of the importance of the format of the code of a website, there are automated evaluation tools that can be used to help assess the accessibility of a webpage,11 however, they require the addition of knowledgeable human evaluation.12 This is because, for example, a tool may be able to judge that the code of a webpage works; however, it cannot determine if what is being said makes sense and produces an equitable experience. In light of this, the Web Accessibility Initiative (WAI), an organization that works with stakeholders such as “industry, disability organizations, government, accessibility research organizations, and more,”13 created the Web Content Accessibility Guidelines (WCAG). WCAG 2.1,14 published in 2018, is the most recent update.15 These guidelines were created to fulfill the mission of this group, organized by the World Wide Web Consortium (W3C)–an international community made of “Member organizations, a full-time staff, and the public”16–to work to increase the accessibility of the Web for individuals with disabilities.17

Web accessibility is important to museums for several reasons. At the most obvious level, it allows individuals with disabilities to use museum resources to learn from the institutions and participate from home, something the COVID-19 pandemic demonstrated works.18 This is additionally important as, even with the opening up of museums, some individuals may not be able or comfortable visiting the physical museum space, meaning the technological resources must be accessible if a museum wants to create inclusive experiences for all of their visitors.19 With the Digital Age in museums having been underway for many years, this is an important step to continue to create equitable serve for all visitors.20

Web accessibility also improves experiences for those without disabilities, such as individuals who are elderly, have low literacy or fluency in the language, or do not have new technology or fast connection to the Internet, though only accessibility for individuals with disabilities will be focused on in this paper.21 The elderly will progressively grow to a larger portion of the population, due to differing generational sizes, becoming a greater percentage of visitors to consider. They will also continue to grow in significance when considering digital technologies as current generations, who grew up with the Web, experience limitations inherent to aging and yet still desire to equitably interact with the Web.22 In addition, the increase of web accessibility of webpages improves their search engine optimization (SEO), which, at its most basic level, increases a links chance of appearing on a search engine and so being viewed.23 The use of digital resources has also been shown not to decrease physical visitors, but to better prepare them. This means that a greater likelihood of visitors viewing the digital site will increase their chance of visiting and having a good experience at the museum.24 These are only a few of the benefits seen by adoption of web accessibility in digital technology.

Practical Ways to Increase Web Accessibility in Digital Collections

As explained by the WAI in the Web Content Accessibility Guidelines (WCAG) 2.1, there are four main principles that can be used to judge the web accessibility of a site. These principles are perceivability, operability, understandability, and robustness. If any of these four principles are not achieved, then users with disabilities will not be able to have an equitable experience on a webpage.25 Underneath each of these principles on the guideline is an extensive list of important practical ways to create or maintain these principles on the Web. However, for a museum to begin to move towards a more web accessible digital collection, one may look at Sina Bahram’s article that lists ten basic practical methods to begin to make a museum website more accessible based on the WCAG 2.1.26 Though this is by no means the maximum to strive to achieve, as Bahram’s states, these are important initial steps, and so may be used as baseline criteria for web accessibility in digital collections. These ten practices, all of which are also included in the WCAG 2.1, are as follows:

- Write alt text for images

- Use heading levels on text

- Caption, transcribe, and describe videos

- Watch for color and contrast

- Label controls well

- Make your site zoom-friendly

- Make controls accessible without a mouse

- Label and style links clearly

- Specify the page language in the code

- Validate your code.27

To begin to understand practical ways for museums to implement web accessibility, these recommendations will be applied to the digital collection of the Smithsonian National Museum of American History (NMAH), made up of artifacts and archival material about the history of the United States.28 Due to the content of the collection and usage of only publicly accessible knowledge, the third and tenth criteria will not be discussed. However, all of these recommendations are important to be aware of when considering web accessibility and the content on a digital collection or other online resource as the relevance of each of these may change with different content.

A Case Study: The Smithsonian National Museum of American History (NMAH)

Before beginning this critique of the NMAH’s digital collection, I would like to preface that, as stated on their website, this collection is a work in progress.29 I recognize that they are in the process of digitizing an extensive collection but achieving web accessibility can be done at any stage of the process, including from the start, making a critique appropriate. In consideration of this fact, however, the objects that I used to review the digital collection all appear to have had more extensive work done, such as having a description and image(s). These webpages will hopefully represent the NMAH’s current goals and format for creating and updating object webpages. The six objects selected are as follows:

- Country Store Shop Sign

- Feedsack Dress

- Battle between the Monitor and Merrimac

- 1837 Swasey’s Patent Model of a Cloth Napping Machine

- Medal, “I Take Responsibility”, 1834

- Caster

To analyze these pages, I used VoiceOver Utility30 as well as the HTML source code of a webpage that can be accessed with no additional privileges. In addition, as an individual without a physical disability, my use of these tools included the audio and visual inputs I perceived. This was my first experience actively using screen readers; however, my hope is that this will partially assist in my critique as access should be created with new users in mind to increase web accessibility. Lastly, I had access to high-speed internet and up to date software while conducting this critique, limiting my ability to judge the influence of these factors on both the website and the tools used by individuals. All of these aspects of my experience should be considered, and, especially due to this, my critique should be used as a starting point, not in place of actively including individuals with disabilities when accessing your own digital collection.

1. Write alt text for images

Alt Text, short for alternative text, is a short description attached to visual content on the Web. This is often found on images or videos and is intended to provide descriptions of the visual content being displayed. This is especially important as screen readers will often be unable to provide this information or effective descriptions without the inclusion of alt text.

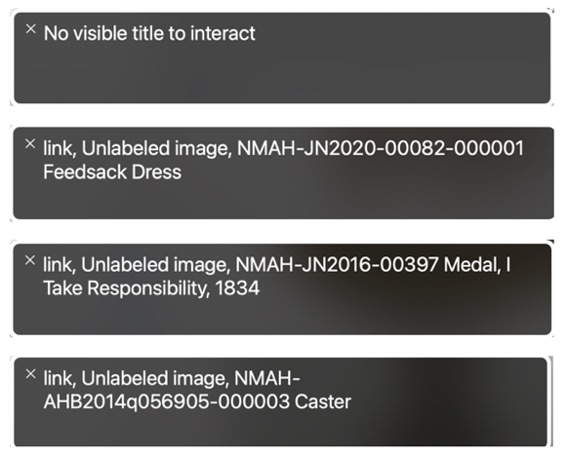

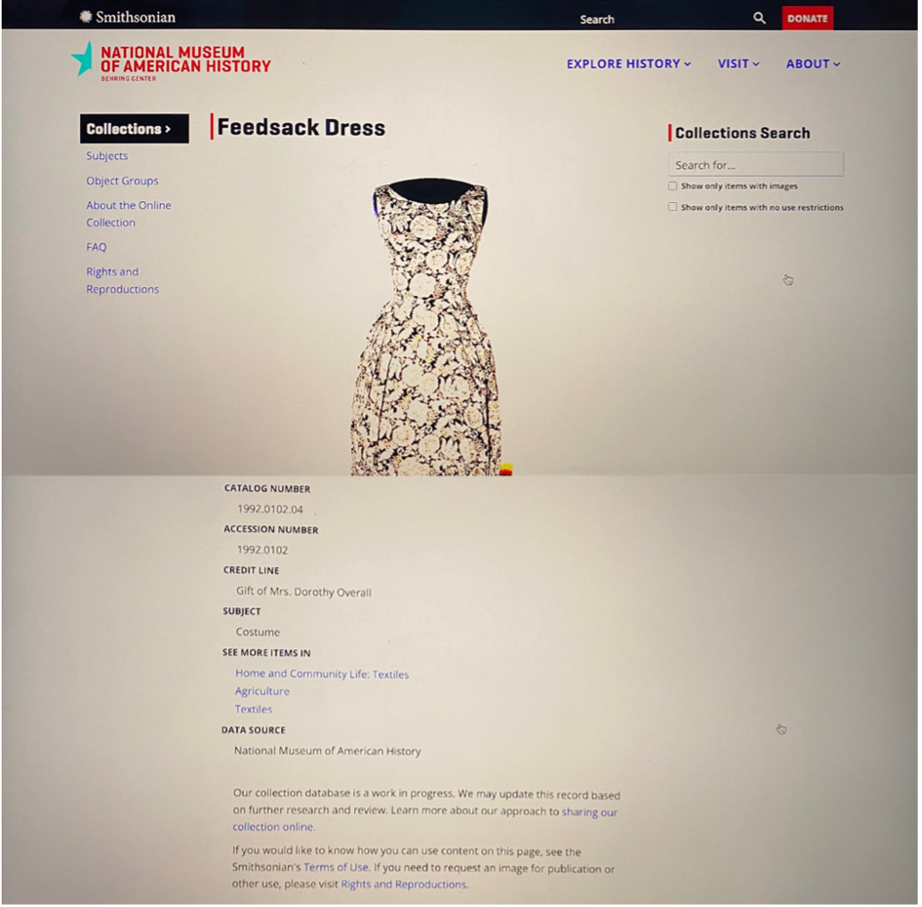

When selecting each of the images in all of the object webpages, there appears to be no alt text. When an object was selected, VoiceOver either stated that there is “[n]o visible title” or read the file name, shown in Figure 1.31 Of all the objects looked at, there were only three that had a file name, but no additional information was provided. Additionally, the file name is not descriptive, containing only “NMAH,” a list of numbers and letters that, to the public, has no meaning, and the object name. After reading the file name, VoiceOver then states that there is no title provided in the same way as the other objects viewed. Consequently, though the file name may provide information on the source of the image and the name of the object in it, it provides no information specific to the visual content of the image.

2. Use heading levels on text

Especially in relation to screen readers, using correct formatting in a website’s HTML code is crucial. Screen readers will identify if different levels of headings are used, which then provides context to visitors on how the text is split. Without this, crucial understanding of headers, lists, and separation is lost that can fundamentally change what is being expressed. It is especially important that this is done in the code, not just sizing or coloring of font, as screen readers may not be able to detect such changes if they are not identified in the code.

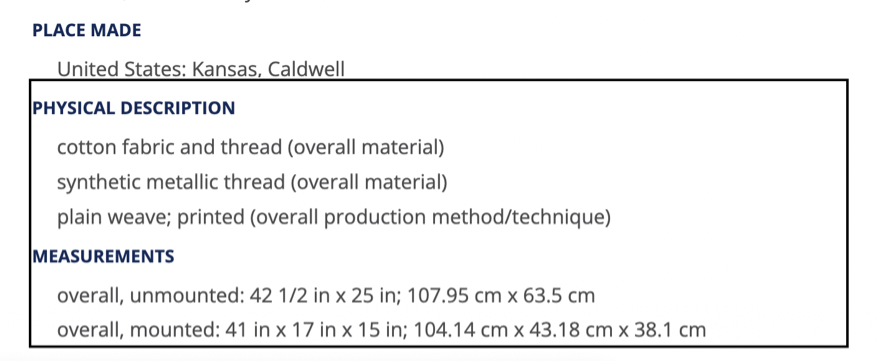

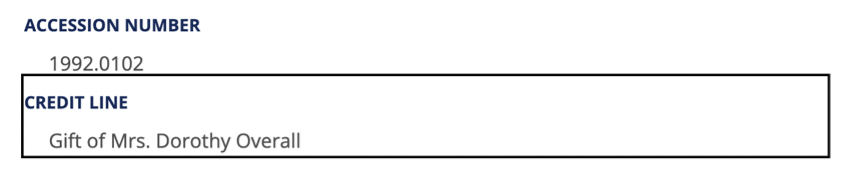

The webpages, specifically their code, does not set up conducive headings for screen reader technology. Though the name of the object at the start of the page is differentiated as a header, the different descriptive groups, such as “DESCRIPTION” and “OBJECT NAME,” are not identified as sub-headers. In addition, each grouping of information is not consistently separated, as seen in Figure 2 and Figure 3.32 Though the “CREDIT LINE” was split into two separate lines, the “PHYSICAL DESCRIPTION” and “MEASUREMENTS” information were identified as a singular list, meaning no verbal information was provided to explain that these two are separate lists under these two sub-headers. This can be shown by the fact that the black box, created by VoiceOver to indicate what text is grouped together, covers multiple lists. In addition, the description in Figure 2 stated that there were seven lines, but that Figure 3 had two lines. In essence, no information is provided that explains that “PHYSICAL DESCRIPTION,” “MEASUREMENTS,” and “CREDIT LINE” are sub-headings with lists under them. This limitation could be solved through modification of the HTML code of the website. By specifying in the code that aspects such as “DESCRIPTION” are sub-headings, the screen reader would be able to differentiate the text into groups, which would be verbally specified.

4. Watch for color and contrast

When it comes to the color and contrast of a webpage, it is firstly important to recognize that nothing should be conveyed by color alone as some individuals are not able to perceive color. Any use of color change must be joined by an indicator of that information that is not based on color.33 However, when considering color choices, the contrast of these colors should be considered as well. At a minimum, the WCAG 2.1 states that all texts should have a contrast ratio of 4.5:1 while large text should have 3:1.34 There are some tools that may be used to judge the contrast of a webpage, however, for this analysis, manual changing of contrast on a laptop was used.

Overall, the NMAH’s website is fairly effective in the color contrast. Certain aspects were lost, however, the main functions of the digital collection aspect of the website was conveyed. As shown in Figure 4,35 certain outlines that are marked by color cannot be noted in high contrast. However, these color outlines are not fundamental to understanding as the structure of the webpage and text still conveys groupings. In addition, though the color change of the headings is not distinctly shown, they are also differentiated by use of only capitalization. There is an issue with the usage of hyperlinked text due to the fact that its nature is only identified by color and no other markers, but this will be discussed in 8. Label and style links clearly.

5. Label controls well

When it comes to controls on the webpage, labeling each in the code is crucial for individuals using technology like screen readers. Labeling of these buttons will change how the screen reader verbally describes them which, especially if individuals cannot see the context of the button on the screen, is pivotal for understanding what it is used for.

Consistent over each of the objects, the NMAH was effective in achieving this criterion. Each of the controls that I noted had descriptors attached to them specifying their usage. For example, if multiple images were attached for an object, the options to move to the previous or next image, which were marked with “>” and “<,” were identified, respectively, as “PREVIOUS” and “NEXT” by the screen reader. The “+” and “-” buttons that allowed a visitor to zoom into and out of an image were identified as “Zoom in” and “Zoom out,” respectively, and the option to return to the view of the image without zooming, marked by a button that looked like a house, was identified as “Go home.” Though the last of these may be somewhat confusing, I would argue that this relates more to the overall experience then specific to the screen reader as I was confused by the function of the button before using this tool. The other options on the image page were also reviewed, and all appeared effective.

The only critique that could be provided is on the two separate search bars on the webpages. One found at the top of the page on the header for the website and the other found within the page specific to searching the digital collection, these were identified as “Search edit text” and “Search for… menu pop up.”36 Additionally, the button to submit a search on the header, appearing to be a magnifying glass, was identified as “Go!” Though this is relatively okay as one may be able to assume the purpose of each of these, the descriptions, especially in the header, could be clarified to indicate more directly the purposes.

6. Make your site zoom-friendly

As a general recommendation, it is suggested that all webpages should be able to achieve at least 200% magnification without effecting the ability of viewers to understand the content. A webpage must be formatted to consider this so that magnification to this percentage does not cut off portions of the content or shift it in confusing orders.

The NMAH’s webpages are very effective in fulfilling this criterion. Each page allows for at least 200% magnification by changing the format of the page to still include all of the content. For example, as shown in Video 1,37 the tool bars previously on the side are moved to the top of the page and the images are changed to cover the entire page. Upon investigation, the pages allow for magnification to 300% and 400% through the shifting of their format to allow for logical organization of information and the shifting of box sizes to stop any text from being cut. Though the images are not increased in size after 200% magnification, they can be selected and then magnified further.

7. Make controls accessible without a mouse

When it comes to interacting with a webpage, all controls should be usable without the use of a mouse. Those with physical disabilities may not be able to utilize a mouse, and so all functions should be accessible through the sole usage of a keyboard. An important part of this is clear indication on where the user and their controls are focused on.

The NMAH’s digital collection specific controls were effective in this category. Each control, when selected, was encircled by a box-like shape to indicate where control was, shown in Figure 5.38 In addition, the page was moved with the shifting of the control.

However, the header of the webpage was only partially effective as, though sometimes using the same method, its “EXPLORE HISTORY,” “VISIT,” and “ABOUT” selections where only indicated by a slight darkening of color. This is shown in Figure 6 where the “EXPLORE HISTORY” button is currently being selected. In addition, no perceivable change could be found when control was on the search and “DONATE” button in the header.

8. Label and style links clearly

When it comes to including links in text, it is important to consider multiple disabilities in how links are attached. Firstly, if screen readers are being used, the links must be attached to words that indicate what the link will go to as a screen reader only provides the information that a link is given and what words it is attached to. In addition, links are often noted by a change in color and/or formatting. It is important that color is not the only indication as some visitors may not be able to see colors but not require a screen reader. The frequent recommendation is that linked words are indicated by a change in color and underlining of the text.39

The NMAH’s webpages fall in the middle for this criterion. Though the links used are hyperlinked to text that is descriptive of what the link is meant for, shown in Figure 7,40 they are only denoted by blue text instead of a non-color-based marker, such as underlining. Though this color contrast between the black text, dark blue of the sub-headers, and linked text may be seen by some visitors, those with visual disabilities may not be able to tell the difference. While the sub-headers are also denoted by the bolding of text and the indention of text underneath each sub-header, there is no differentiation of hyperlinked text and normal text other than the change in color. This was consistent throughout all the objects.

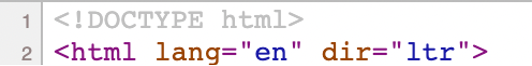

9. Specify the page language in the code

Especially for the usage of any screen readers, it is important to specify in the HTML code of the webpage what language is being used. This is crucial for visitors who use a different language, as a screen reader may assume the language if not provided which can produce unintelligible content for the viewer. With the global nature of the Web, this is crucial information that should be provided.

All of the webpages selected for analysis were consistent and fulfilled this criterion. As seen in the HTML source code for each, the top two lines are shown in Figure 8. These lines specifies that the language is in English through “lang=‘en’,” and that the text should be read from left to right through “dir=‘ltr’.”

Reminders and Looking Forward into the Future

When attempting to implement web accessibility in a museum, it is crucial to include all areas of the museum in this process. Web accessibility needs to be a part of the entire museum’s mission to be effective and assist the most extensive number of individuals and groups.41 Everyone in the museum should be actively participating in this goal.42 It is also important to include diverse and overarching groups, instead of certain departments within the museum or museum staff alone, as this will increase the ability of your web accessibility methods to be applicable and beneficial to a larger group.43 In addition to this, it is crucial to include individuals with disabilities in the creation of innovations and the judgement of their effectiveness. As Habe Girma, an advocate and the first deafblind graduate of Harvard Law School, explained— “[e]mployees with disabilities drive innovation. Disability creates a constraint, and embracing constraints spurs inventive solutions… Different lived experiences… generate the new ideas that lead to discoveries.”44

It is also important to remember to start the process, no matter your current resources, and implement consideration of web accessibility at the beginning of and throughout new projects. There are many individuals with numerous types and combinations of disabilities, consequently, increasing web accessibility may often require numerous steps. Though a museum can include web accessibility at the start of a project, making previous projects and resources web accessible will be a process that, most likely, cannot be done all at once. Sina Bahram best summarizes this point when saying,

We will not get these solutions 100% correct the first, second, or tenth time, but we cannot allow fear of the lack of perfection to continue being used as a justification for doing very little. Inclusion is not a binary pursuit with a finite destination. Inclusion is a state of thinking and acting towards a shared purpose based on a commitment to iteration, refinement, and self-improvement.45

This is not meant to be demoralizing or be used as a reason to deprioritize web accessibility, but instead a reminder that it is a process, to start now, and to always be open for critique.

In addition, it is important to remember that the criteria provided above is not an exhaustive list of all the methods that can be used to make digital collections more web accessible for individuals with disabilities, but instead a few initial steps that may be beneficial for sites. There is a more extensive list that can be found on the Web Content Accessibility Guidelines (WCAG) 2.1–which is intended to increase accessibility for individuals with many types of disabilities, including auditory, cognitive, neurological, physical, speech, and visual disabilities–as well as other examples and suggestions for practical ways to make digital projects more web accessible for individuals with disabilities.46

Notes

-

Ioannis Drivas et al., “Content Management Systems Performance and Compliance Assessment Based on a Data-Driven Search Engine Optimization Methodology,” Information 12, no. 7 (June 24, 2021): 1, https://doi.org/10.3390/info12070259. ↩︎

-

Drivas et al., 1-2. ↩︎

-

Suzanne Keene, “Collections and Digitization,” in Fragments of the World: Uses of Museum Collections, 1st ed. (Amsterdam: Elsevier Butterworth-Heinemann, 2005), 152. ↩︎

-

Shawn Lawton Henry, “Introduction to Web Accessibility,” Web Accessibility Initiative (WAI), March 31, 2022, https://www.w3.org/WAI/fundamentals/accessibility-intro/. ↩︎

-

Jim Thatcher et al., Web Accessibility: Web Standards and Regulatory Compliance (Berkeley, CA: Friends of Ed; Distributed to the book trade worldwide by Springer-Verlag New York, 2006), 2. ↩︎

-

Henry, “Introduction to Web Accessibility.” ↩︎

-

Thatcher et al., Web Accessibility, 2. ↩︎

-

“What Is Universal Design… Inclusive Design..Design-for-All?,” Institute for Human Centered Design, accessed November 9, 2022, https://ihcd-api.s3.amazonaws.com/s3fs-public/file+downloads/Inclusive+Design+Cheat+Sheet+6+18.pdf ; Sina Bahram, “The Inclusive Museum,” Prime Access Consulting (blog), October 1, 2018, https://www.pac.bz/blog/the-inclusive-museum/. ↩︎

-

Lourdes Moreno and Paloma Martinez, “Overlapping Factors in Search Engine Optimization and Web Accessibility,” Online Information Review 37, no. 4 (August 2, 2013): 564–65, https://doi.org/10.1108/OIR-04-2012-0063. ↩︎

-

Sina Bahram, “10 Best Practices of Accessible Museum Websites,” American Alliance of Museums (blog), January 7, 2021, https://www.aam-us.org/2021/01/07/10-best-practices-of-accessible-museum-websites/. ↩︎

-

Eric Eggert and José Ramón Hilera González, “Web Accessibility Evaluation Tools List,” Web Accessibility Initiative (WAI), March 2016, https://www.w3.org/WAI/ER/tools/. ↩︎

-

Shawn Lawton Henry, “Evaluating Web Accessibility Overview,” Web Accessibility Initiative (WAI), February 2, 2022, https://www.w3.org/WAI/test-evaluate/. ↩︎

-

Shawn Lawton Henry and Judy Brewer, “About W3C WAI,” Web Accessibility Initiative (WAI), March 10, 2020, https://www.w3.org/WAI/about/. ↩︎

-

Andrew Kirkpatrick et al., “Web Content Accessibility Guidelines (WCAG) 2.1,” The World Wide Web Consortium, June 5, 2018, https://www.w3.org/TR/WCAG21/. ↩︎

-

The draft for the next version, WCAG 2.2, has been published, but the finalized guidelines are not scheduled to be completed until 2023. ↩︎

-

“About W3C,” The World Wide Web Consortium, accessed November 9, 2022, https://www.w3.org/Consortium/. ↩︎

-

Thatcher et al., Web Accessibility, xxxvi. ↩︎

-

Rafie R. Cecilia, “COVID-19 Pandemic: Threat or Opportunity for Blind and Partially Sighted Museum Visitors?,” Journal of Conservation and Museum Studies 19, no. 1 (March 29, 2021): 1, https://doi.org/10.5334/jcms.200; Cecilia, “COVID-19 Pandemic,” 5. ↩︎

-

Cecilia, “COVID-19 Pandemic,” 6. ↩︎

-

Jane D. Monson, Getting Started with Digital Collections: Scaling to Fit Your Organization (Chicago: ALA Editions, an imprint of the American Library Association, 2017), vii. ↩︎

-

Bahram, “10 Best Practices of Accessible Museum Websites”; Kirkpatrick et al., “Web Content Accessibility Guidelines (WCAG) 2.1”; Moreno and Martinez, “Overlapping Factors in Search Engine Optimization and Web Accessibility,” 565; Thatcher et al., Web Accessibility, 8–10; Haben Girma, “Break down Disability Barriers to Spur Growth and Innovation,” The Financial Times Limited, September 13, 2017, http://proxygw.wrlc.org/login?url=https://www.proquest.com/trade-journals/break-down-disability-barriers-spur-growth/docview/1950569364/se-2?accountid=11243.; Bahram, “The Inclusive Museum.” ↩︎

-

Moreno and Martinez, “Overlapping Factors in Search Engine Optimization and Web Accessibility,” 565; “What Is Universal Design… Inclusive Design..Design-for-All?” ↩︎

-

Moreno and Martinez, “Overlapping Factors in Search Engine Optimization and Web Accessibility,” 576. ↩︎

-

Nataša Krstić and Dejan Masliković, “Pain Points of Cultural Institutions in Search Visibility: The Case of Serbia,” Library Hi Tech 37, no. 3 (September 16, 2019): 497, https://doi.org/10.1108/LHT-12-2017-0264. ↩︎

-

Kirkpatrick et al., “Web Content Accessibility Guidelines (WCAG) 2.1.” ↩︎

-

Bahram, “10 Best Practices of Accessible Museum Websites.” ↩︎

-

Bahram, “10 Best Practices of Accessible Museum Websites.” ↩︎

-

“Collections,” National Museum of American History, accessed November 9, 2022, https://americanhistory.si.edu/collections ; “About the Online Collection,” Online Collection, National Museum of American History, accessed November 9, 2022, https://americanhistory.si.edu/collections/about-online-collection. ↩︎

-

National Museum of American History, “Collections”; National Museum of American History, “About the Online Collection.” ↩︎

-

This is a screen reader product of Apple Inc. available on a MacBook. The Version 10 (864) was used for this paper. ↩︎

-

“Feedsack Dress,” Online Collection, National Museum of American History, accessed November 9, 2022, https://americanhistory.si.edu/collections/search/object/nmah_1105750 ; “Medal, '91I Take Responsibility', 1834,” Online Collection, National Museum of American History, accessed November 9, 2022, https://americanhistory.si.edu/collections/search/object/nmah_504965 ; “Caster,” Online Collection, National Museum of American History, accessed November 9, 2022, https://americanhistory.si.edu/collections/search/object/nmah_300618. ↩︎

-

National Museum of American History, “Feedsack Dress.” ↩︎

-

Bahram, “10 Best Practices of Accessible Museum Websites.” ↩︎

-

Kirkpatrick et al., “Web Content Accessibility Guidelines (WCAG) 2.1.” ↩︎

-

National Museum of American History, “Feedsack Dress.” ↩︎

-

“Country Store Shop Sign,” Online Collection, National Museum of American History, accessed November 9, 2022, https://americanhistory.si.edu/collections/search/object/nmah_662011. ↩︎

-

“Battle between the Monitor and Merrimac,” Online Collection, National Museum of American History, accessed November 9, 2022, https://americanhistory.si.edu/collections/search/object/nmah_324940. ↩︎

-

National Museum of American History, “Battle between the Monitor and Merrimac.” ↩︎

-

Bahram, “10 Best Practices of Accessible Museum Websites.” ↩︎

-

“1837 Swasey’s Patent Model of a Cloth Napping Machine,” Online Collection, National Museum of American History, accessed November 9, 2022, https://americanhistory.si.edu/collections/search/object/nmah_1071147. ↩︎

-

Bahram, “10 Best Practices of Accessible Museum Websites.” ↩︎

-

Ruth Starr, “Prioritizing Image Descriptions and Digital Equity at Cooper Hewitt,” American Alliance of Museums (blog), May 13, 2020. https://www.aam-us.org/2020/05/13/prioritizing-image-descriptions-and-digital-equity-at-cooper-hewitt/. ↩︎

-

Starr, “Prioritizing Image Descriptions and Digital Equity at Cooper Hewitt”; Keene, “Collections and Digitization,” 151. ↩︎

-

Girma, “Break down Disability Barriers to Spur Growth and Innovation.” ↩︎

-

Bahram, “The Inclusive Museum.” ↩︎

-

Kirkpatrick et al., “Web Content Accessibility Guidelines (WCAG) 2.1”; Thatcher et al., Web Accessibility, 20–32; Henry, “Introduction to Web Accessibility.” ↩︎